Thinking Critically About Written Texts and Images

Thinking About Written Texts

To be a critical reader, though, you need to be more than a good predictor. In addition to following the thread of communication, you need to evaluate its logic. To do that, you need to ask questions such as these as you consider the argument: Is it fair (i.e., unbiased)? Does it provide credible evidence? Does it make sense, or is it reasonably plausible? Then, based on what you have decided, you can accept or reject its conclusions. You may also consider alternative possibilities so that you can learn more. In this way, you read actively, searching for information and ideas that you understand and can use to further your own thinking, writing, and speaking. To move from understanding to critical awareness, plan to read a text more than once and in more than one way. One good strategy is to ask questions of a text rather than to accept the author’s ideas as fact. Another strategy is to take notes about your understanding of the passage. And another is to make connections between concepts in different parts of a reading. Maybe an idea on page 4 is reiterated on page 18. To be an active, engaged reader, you will need to build bridges that illustrate how concepts become part of a larger argument. Part of being a good reader is the act of building information bridges within a text and across all the related information you encounter, including your experiences.

With this goal in mind, beware of passive reading. If you ever have been reading and completed a page or paragraph and realized you have little idea of what you’ve just read, you have been reading passively or just moving your eyes across the page. Although you might be able to claim you “read” the material, you have not engaged with the text to learn from it, which is the point of reading. You haven’t built bridges that connect to other materials. Remember, words help you make sense of the world, communicate in the world, and create a record to reflect on so that you can build bridges across the information you encounter.

Thinking About Images

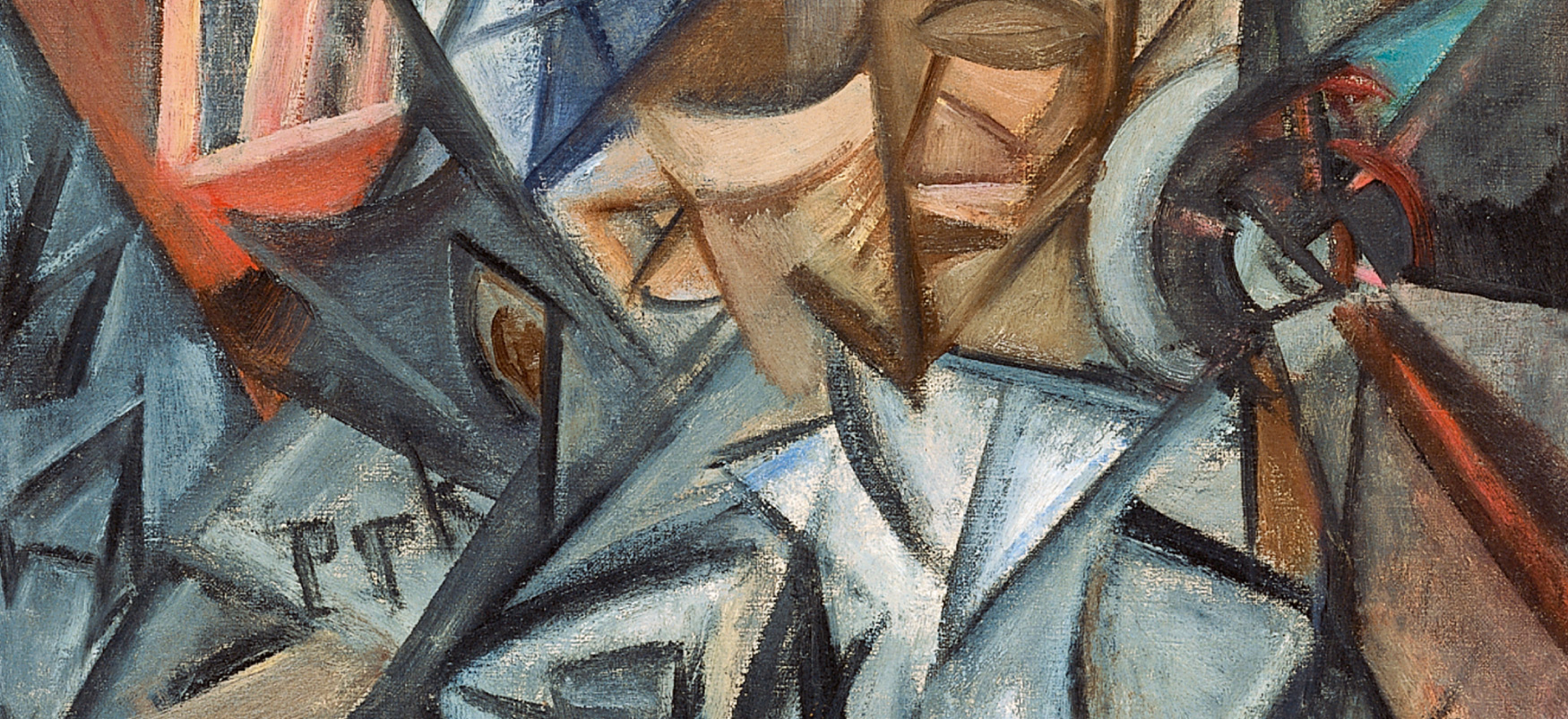

Consider the subject of this painting, Man on the Street, by Russian artist Olga Rozanova (1886–1918). Now, consider the way the subject is presented: cool colors, fragmented lines, distorted perspective. What is the artist saying about the man on the street by presenting him in this way? As soon as you begin to answer this question, you are analyzing a visual text.

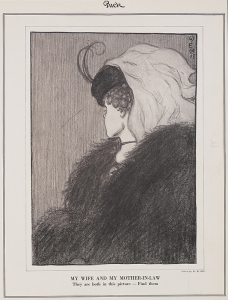

While these playful aspects of images are important, you should also recognize how images fit into the rhetorical situation. When viewing images, consider the same elements, such as context and genre. You may find multiple perspectives to consider. In addition, where images show up in a text or for an audience might be important. These are all aspects of understanding the situation and thinking critically. Engaged readers try to connect and build bridges to information across text and images.

Academic Writing

- Analysis: detailed breakdown or other explanation of some aspect or aspects of a text. Analysis helps readers understand the meaning of a text.

- Authority: credibility; background that reflects experience, knowledge, or understanding of a situation. An authoritative voice is clear, direct, factual, and specific, leaving an impression of confidence.

- Context: setting—time and place—of the rhetorical situation. The context affects the ways in which a particular social, political, or economic situation influences the process of communication. Depending on context, you may need to adapt your text to audience background and knowledge by supplying (or omitting) information, clarifying terminology, or using language that best reaches your readers.

- Culture: group of people who share common beliefs and lived experiences. Each person belongs to various cultures, such as a workplace, school, sports team fan, or community.

- Evaluation: systematic assessment and judgment based on specific and articulated criteria, with a goal to improve understanding.

- Evidence: support or proof for a fact, opinion, or statement. Evidence can be presented as statistics, examples, expert opinions, analogies, case studies, text quotations, research in the field, videos, interviews, and other sources of credible information.

- Media literacy: ability to create, understand, and evaluate various types of media; more specifically, the ability to apply critical thinking skills to them.

- Meme: image (usually) with accompanying text that calls for a response or elicits a reaction.

- Paraphrase: rewording of original text to make it clearer for readers. When they are part of your text, paraphrases require a citation of the original source.

- Rhetoric: use of effective communication in written, visual, or other forms and understanding of its impact on audiences as well as of its organization and structure.

- Rhetorical situation: instance of communication; the conditions of a communication and the agents of that communication.

- Social media: all digital tools that allow individuals or groups to create, post, share, or otherwise express themselves in a public forum. Social media platforms publish instantly and can reach a wide audience.

- Summary: condensed account of a text or other form of communication, noting its main points. Summaries are written in one’s own words and require appropriate attribution when used as part of a paper.

- Tone: an author’s projected or perceived attitude toward the subject matter and audience. Word choice, vocal inflection, pacing, and other stylistic choices may make the author sound angry, sarcastic, apologetic, resigned, uncertain, authoritative, and so on.

As you read through these terms, you likely recognize most of them and realize you are adept in some rhetorical situations. For example, when you talk with friends about your trip to the local mall, you provide details they will understand. You might refer to previous trips or tell them what is on sale or that you expect to see someone from school there. In other words, you understand the components of the rhetorical situation. However, if you tell your grandparents about the same trip, the rhetorical situation will be different, and you will approach the interaction differently. Because the audience is different, you likely will explain the event with more detail to address the fact that they don’t go to the mall often, or you will omit specific details that your grandparents will not understand or find interesting. For instance, instead of telling them about the video game store, you might tell them about the pretzel café.

As part of your understanding of the rhetorical situation, you might summarize specific elements, again depending on the intended audience. You might speak briefly about the pretzel café to your friends but spend more time detailing the various toppings for your grandparents. If, by chance, you have previously stopped to have a pretzel, you might provide your analysis and evaluation of the service and the food. Once again, you are engaged in rhetoric by showing an understanding of and the ability to develop a strategy for approaching a particular rhetorical situation. The point is to recognize that rhetorical situations differ, depending, in this case, on the audience. Awareness of the rhetorical situation applies to academic writing as well. You change your presentation, tone, style, and other elements to fit the conditions of the situation.

LICENSE AND ATTRIBUTION

Adapted from:

- Michelle Bachelor Robinson’s, Maria Jerskey’s, and Toby Fulwiler’s “The Digital World: Building on What You Already Know to Respond Critically” of Writing Guide with Handbook, 2023, used according to CC BY 4.0.

- Michelle Bachelor Robinson’s, Maria Jerskey’s, and Toby Fulwiler’s “Print or Textual Analysis: What You Read” from Writing Guide with Handbook , 2023, used according to CC BY 4.0.