Team Writing

Team writing, or collaborative writing, has many benefits. Because many companies believe the advantages of collaborative writing outweigh the disadvantages, many companies choose to have employees work together on projects with writers as part of those teams. However, the positive results often attained on company projects rely heavily on the formulation of the team, skill sets, and positive group dynamics, something we’ll talk about a little later. For now, let’s look at the advantages of collaborative writing below.

Collaborative writing creates a more enjoyable work environment. Because members of the team share the responsibilities of the project or writing, they must communicate verbally and electronically, and in some instances, they must communicate virtually. These interactions often work to improve and foster a collegial atmosphere, producing a workplace that adds to the overall good of the company.

Collaborative writing creates a product that considers diverse audiences. When a team is created with the thought of diversity, the work they produce tends to be more sensitive to varied cultures and audiences. If, for example, the team incorporates the skill sets of women, men, members of the LGBT community, cis and non-cis males and females, as well as members of various races and cultures, the final product will have taken into consideration the complexities of multiple communities, something that is not so easily attained by a single community of writers.

Collaborative writing provides an opportunity for employees – both new and not-so-new – to explore skills as both leaders and subordinate team members. A sage once said, “To be a good leader, you must learn to follow.” Now and then, a true leader is born, but a really successful leader is one who has learned to follow. Employees who have been groomed and allowed to rise through the ranks often make the most successful leaders because they are able to understand the tasks at hand and empathize with the challenges created as a result of the task. Likewise, when organizations choose to rotate the roles of team members, it allows employees to participate in roles such as team lead, recorder, researcher, editor, reporter, and more.

Collaborative writing fosters engagement through active learning. When employees write collaboratively, they put themselves in a position to either learn from or hone their dormant skills as they work with colleagues who may be more adept at a certain skill than they are.

Collaborative writing helps to grow the organization. When all of the members of the team see their contribution as not just important but imperative to the success of the project, they contribute as owners rather than workers, ultimately affecting the bottom line – profit. And when a company has become successful as a result of fully engaged employees who see their contributions as the reasons behind the company’s success, the longevity of the company is inevitable.

Collaborative writing produces a superior product or outcome. When performed correctly (see notes above about what true collaborative writing is and is not), the project’s end result will be superior to anything produced outside of collaboration because the most advanced skills will have been utilized and because the team members will have drawn on their commitment to the end result for the good of not just themselves but the entire company.

Collaborative writing draws on the use of technology. With the emergence of so many new collaboration tools and other technological advances designed to make writing more efficient, employees are better able to engage with their colleagues and produce projects in less time and with fewer obstacles than they could without those tools. There are various types of collaboration tools, including e-mail, voicemail, instant messaging (IM), VoIP video call (or voice over IP), online calendars, wikis, and shared document workspaces.

Project: A Report on Current Cloaking Technologies

- Shawn S.: Electrical engineering major, currently doing basic office-management chores at a law firm

- Tracey K.: Senior English major, hoping this course helps with employment prospects

- Sanjiv Gupta: Computer science major, currently doing computer graphics at a software development shop

- Jeon Chang Yeon: Soon-to-be electrical engineering major, still developing English language skills

- Alice B.: Undeclared major with a nontechnical focus, possibly in the wrong course, no stated skills

Planning the Project

Once you’ve assembled your writing team, most of the work is the same as it would be if you were writing by yourself—except that each phase is a team effort. Specifically, meet with your team to decide or plan the following:

Planning Stages

- Analyze the writing assignment.

- Pick a topic.

- Define the audience, purpose, and writing situation.

- Brainstorm and narrow the topic.

- Create an outline.

- Plan the information search (for books, articles, etc., in the library).

- Plan a system for taking notes from information sources.

- Plan any graphics you’d like to see in your writing project.

- Agree on style and format questions (see the following discussion).

- Develop a work schedule for the project and divide the responsibilities (see the following).

Capture your team’s profiles and decisions in a simple team-planning document. It can contain the key dates in the team schedule, a tentative outline of the document to be team-produced, formatting agreements, individual writer assignments, word-choice preferences, and so on. Below, a by-laws document is mentioned. That can be incorporated into the team plan as well.

Much of the work in a team-writing project must be done by individual team members on their own. However, if your team decides to divide up the work for the writing project, try for at least these minimum guidelines:

- Have each team member responsible for the writing of one major section of the paper.

- Have each team member responsible for locating, reading, and taking notes on an equal part of the information sources.

You may want to do some of the work for the project that could be done as a team first independently. For example, brainstorming, narrowing, and especially outlining should be done first by each team member on their own; then, get together and compare notes. Keep in mind how group dynamics can unknowingly suppress certain ideas and how less assertive team members might be reluctant to contribute their valuable ideas in the group context.

After you’ve divided up the work for the project, write a formal chart and distribute it to all the members.

Scheduling the Project and Balancing the Workload

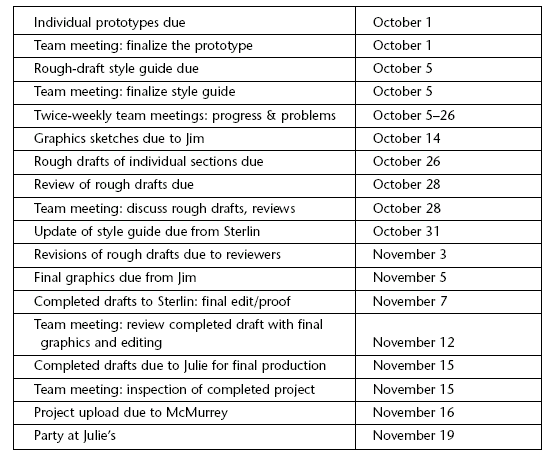

Early in your team writing project, set up a schedule of key dates. This schedule will enable you and your team members to make steady, organized progress and complete the project on time. As shown in the example schedule below, include not only completion dates for key phases of the project but also meeting dates and the subject and purpose of those meetings. Notice these details about that schedule:

- Several meetings are scheduled in which members discuss the information they are finding or are not finding. (One team member may have information another member is looking everywhere for.)

- Several meetings are scheduled to review the project details, specifically the topic, audience, purpose, situation, and outline. As you learn more about the topic and become more settled in the project, your team may want to change some of these details or make them more specific.

- Several rough drafts are scheduled. Team members peer-review each other’s drafts of individual sections at least twice, the second time to see if the recommended changes have worked. Once the complete draft is put together, it, too, is reviewed twice.

Anticipating Problems and Creating Team By-laws

You can think ahead to resolve typical problems that can arise in a team project and document your team’s agreements about these matters in a by-laws document:

Workload Imbalance

- When you work as a team, there is always the chance that one of the team members, for whatever reason, may have more or less than a fair share of the workload. Therefore, it’s important to find a way to keep track of what each team member is doing. A good way to do that is to have individual team members keep a journal or log of what kind of work they do and how much time they spend doing it.

- Both during and at the end of the project, if there are any problems, the journal should make the issue very clear and enable a more equitable balancing of the workload. At the end of the project, team members can add up their hours spent on the project; if anyone has spent a little more than their share of time working, the other members can make up for it by buying them dinner or another similar reward. Similarly, as you reach the end of the project, if it’s clear from the journals that one team member’s work responsibilities turned out, through no fault of their own, to be smaller than those of the others, they can make up for it by doing more of the finish-up work such as typing, proofing, or copying.

Team members without relevant skills

- As you can see in the example description of team members’ skills above, one member has no relevant skills with which to contribute to the project. Sometimes, that’s just an indication of that person’s anxiety or lack of interest in engaging in a group project. Of course, each team member in a writing course should contribute a fair share of the writing for a project. However, there are plenty of tasks that do not require technical knowledge, formatting skills, or a sharp editorial eye, for example, typing up and distributing the team plan, the by-laws, minutes of team meetings, and reminding team members of due dates and scheduled meetings. In fact, except for the anxiety or lack of interest, the self-professed unskilled team member might make the best team leader!

Disappearing team members

- If your team is unfortunate enough to have an irresponsible member who simply vanishes, have a plan for what to do about that and document it in your team by-laws. One obvious solution is to kick the team member off the team and inform the instructor if it’s a writing course or the next level of management if it’s a nonacademic organization.

Seemingly entrenched team-member disagreements

- It is amazing how vehemently team members can disagree on aspects of a team-writing project. To prepare for this possibility, have a plan written in your team by-laws that addresses how team members can resolve these matters. Should they be put to a vote? Should you “escalate” the matter to a neutral or higher-level party?

Radically inconsistent writing styles and format

- Because the individual sections will be written by different writers who are apt to have different writing styles, set up a style guide in which your team members list their agreements on how things are to be handled in the paper as a whole. These agreements can range from the high level, such as whether to have a background section, all the way down to picky details, such as when to use italics or bold and whether it is “click” or “click on.” See the excerpt from a project style sheet in the following.

- Before you and your team members write the first rough draft, you can’t expect to anticipate every possible difference in style and format. Therefore, plan to update this style sheet when you review the rough draft of individual sections and especially when the team reviews the complete draft.

The items listed in Figure 3.8 represent agreements team writers have made to ensure the consistency of their paper.

Reviewing Drafts and Finishing

Try to schedule as many reviews of your team’s written work as possible. You can meet to discuss each other’s rough drafts of individual sections and the complete paper. When you do meet, follow the suggestions for peer editing.

A critical stage in team-writing a paper comes when you put together into one complete draft those individual sections written by different team members. It’s then that you’ll probably see how different the tone, treatment, and style of each section is. You must, as a group, find a way to revise and edit the complete rough draft to make it read consistently so that it won’t be so obviously written by three or four different people.

When you’ve finished reviewing and revising, it’s time for the finish-up work to get the draft ready to hand in. That work is the same as it would be if you were writing the paper on your own, only in this case, the workloads can be divided up.

Works Cited

“Strategies for Peer Reviewing and Team Writing” in Online Technical Writingby David McMurrey, which is is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 International License.