Treatment Basics

Team Members

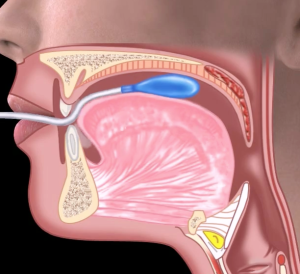

Treatment of dysphagia often engages a team that includes not only the patient, their caregiver(s), primary care physician, and the dysphagia clinician, but also may include rehabilitative specialists, such as physical therapists and occupational therapists, a nutritionist or dietician, and specialty physicians such as neurologists, otolaryngologists, gastroenterologists, or allergists. Box 4.1 includes a list of potential members of the treatment team and their area of input in the management of dysphagia.

Box 4.1: Potential members of the dysphagia team

Connection to Evaluation

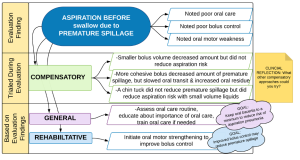

Behavioral treatment performed by the SLP is informed by the results of the evaluation combined with knowledge of the etiologic cause of the swallow deficit. See Box 4.2 for framework overview and Box 4.3 for an example. Box 4.4 provides a sample of the linkage between evaluation findings and treatment options. The extent and focus of the treatment plan may be guided by the patient’s medical status, the needs and concerns of the patient, and the concerns of the medical team. Consideration should be given to the anticipated timeline of the disease or event that caused the dysphagia. For example, for some diagnostic populations, such as stroke, spontaneous recovery may augment the therapeutic effort, especially in the early phases of treatment (Drulia & Ludlow, 2013). Conversely, a patient with a progressive disease does not experience spontaneous swallow improvement. Although treatment may serve to improve and prolong swallow function status, despite treatment, swallow function may decline as the disease progresses.

Box 4.2: Clinical decision making framework

Box 4.3: Sample connection between evaluation finding and treatment approach

Box 4.4: Sample compensatory and rehabilitative (restorative) treatment approaches based on evaluation findings

Activity

Activity 4.1: As you read the chapter, enhance the information in Box 4.4. Enhancements may include additional evaluation findings, other treatment options, and comments on level of evidence to support a specific treatment for a specific deficit.

Connection to Patient

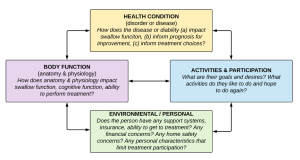

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) is a framework that can be used to insure that treatment is person-centered (Box 4.5). For patients with dysphagia, the framework encourages clinicians to be mindful of the relationship between health status, swallow function, ability to participate in mealtime activities, and the social and physical environment in which the patient resides. When adherence to the ICF model is employed, the SLP considers the swallow physiology, as well as the patient goals and desires when developing a treatment plan. The patient is provided with information about the swallow deficit, which they can use to guide their treatment decisions. Treatment is focused on function with awareness of the individual’s current abilities to independently (when possible) perform activities of daily living and participate with their environment in a meaningful way. For many, mealtime serves as a centerpiece of social interaction and family tradition, highlighting the importance of treatment that addresses improved function within the confines of the specific environment.

Box 4.5: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework developed by the World Health Organization

Clinical Note

Note that the importance of patient engagement and respect for their desires requires not only that the SLP educate the individual about their deficit and potential consequences, but also that effort is made to insure that the patient understood the information. These teach-back moments, where the patient shares his/her understanding of the swallow deficit and treatment recommendations, are evaluated to see if the patient requires clarification or further education.

Clinical Note

For a consensus based example of how the ICF framework can be applied to a patient with dysphagia, please see the attached handout developed by ASHA.

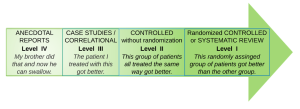

Evaluating Evidence

Evidence-based practice implies that patient care decisions are guided by current best-available evidence (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996). When existing evidence aligns with both the patient’s medical diagnosis and the specific swallow disorder, it is maximally supportive of a treatment choice. However, all evidence is not the same and should be considered with respect to the strength of the evidence. While there are multiple models for measuring the strength or level of evidence, this text will use the framework currently supported by ASHA (2005) (Box 4.6). Evidence is considered in four levels where level I represents the highest level of evidence. Level I evidence is gained from randomized controlled studies or well constructed systematic reviews that incorporate multiple studies. Level II evidence is obtained when studies are well controlled, but lack randomization of participants into treatment groups. Level III evidence refers to supportive data obtained from case studies or correlational studies. Level IV, considered the weakest level of evidence, is obtained from anecdotal report.

Box 4.6: Levels of evidence

When choosing a treatment approach, the clinician should identify a treatment that is supported with the strongest level of evidence. In addition to research evidence, treatment choices are guided by clinical experience and skill, as well as patient and caregiver beliefs and preferences. Evidence-based practice integrates these two pieces (clinician skill and patient preference) with what has been learned from the best research evidence, keeping in mind that randomized control studies carry more weight than anecdotal reports. Thus, when choosing a treatment approach a clinician should ask the following questions: (a) What level of evidence exists for a given treatment with the specific patient population or swallow disorder? (b) Does the clinician have adequate experience or support to correctly perform the treatment with sufficient fidelity? (c) Is the treatment respectful of the patient/family desires and beliefs? The best treatment choices are those that have been tried and tested with a patient population similar to the patient you are treating.

“Want more?”

Learn more about levels of evidence and evidence-based clinical practice from ASHA’s position statement (2005).

Treatment Categories

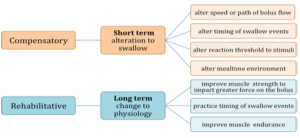

Behavioral treatment provided by the SLP can be grossly divided into compensatory and rehabilitative approaches (Box 4.7). Also, a patient may choose to receive no treatment. Compensatory strategies include short-term alterations to the swallow by manipulating the diet, environment or swallow procedure. Compensatory approaches may include the use of supportive or prosthetic devices. Rehabilitative strategies require time to achieve maximum benefit and may include strengthening of specific muscle groups involved in swallowing or practicing task specific swallow events.

Box 4.7: Categories of swallow treatment

In addition to compensatory and rehabilitative approaches, oral hygiene and free water protocols may be incorporated into the treatment plan. Oral hygiene is an important aspect of dysphagia recovery. In the presence of any aspiration, insufficient oral hygiene results in an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia. This risk is further elevated for individuals who have reduced lung function or a depressed immune response.

Dehydration can impact overall health. For individuals with dysphagia who have been deemed at-risk for aspiration with oral intake, dehydration risk may be increased. Individuals who aspirate may feel discouraged by the risk and, therefore, choose to consume less liquid. Or, they may be encouraged to drink only thickened liquids, and due to dislike, may choose to refrain from drinking any liquids. Free water protocols allow for the intake of water between meals, may improve hydration without increasing the risk of pneumonia provided an individual has good oral hygiene. Therefore, oral hygiene and free water protocols are important considerations in the development of the treatment plan.

Oral Hygiene

The oral cavity is an ideal environment for bacteria. In a healthy individual, the oral flora contains bacteria that are colonized to the mouth (good bacteria). However, undesirable bacteria are also present in the oral cavity. Routine oral hygiene removes debris and bacteria from the oral cavity. Examples of oral hygiene procedures include brushing the teeth, flossing between the teeth, brushing the tongue, and oral rinsing. For edentulous individuals, oral care includes removing and cleaning dentures, and rinsing oral tissues. Dentures should remain out at night to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia (Iinuma et al., 2014).

Clinical Note

Oral spaces, including teeth pockets, can serve as breeding grounds for bacteria. Flossing and use of water pick may decrease the build up of bacteria in oral spaces.

“Want more?”

Oral bacteria increases risk of multiple diseases including colon cancer, heart attacks and strokes (Lux & Lavigne, 2004; Noble, Scarmeas, & Papapanou, 2013), diabetes (Taylor, Loesche, & Terpenning, 2000), and more. Pregnant women with poor oral hygiene are more likely to have a preterm birth (Michalowicz et al., 2006; Buduneli et al., 2005).

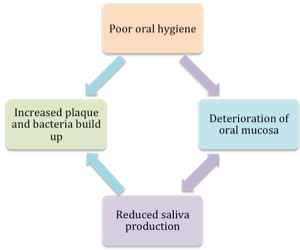

When oral hygiene is lacking, there is the buildup of plaque on and around the teeth and tongue. This plaque serves as a delightful habitat for bacteria and microorganisms (Munro & Grap, 2004). The teeth are considered a particularly desirable location for oral bacteria, because the biofilm on the teeth allows bacteria to adhere to the teeth and keep it from getting washed away and swallowed. The build up of oral bacteria can be reduced by good oral hygiene. When oral hygiene is lacking, aspirated oral contents may be infused with high levels of bacteria in the saliva. The cycle of poor oral hygiene is depicted in Box 4.8.

Box 4.8: Cycle of poor oral hygiene

Clinical Note

Oral hygiene is not the only factor influencing the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Other factors include lung development and health, item(s) being aspirated, and the frequency and amount of aspiration.

Oral health is linked to oral hygiene. Specifically, good oral hygiene leads to improved overall health and a reduced risk of aspiration pneumonia (Muller, 2015). Conversely, there is an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia with poor oral health or oral hygiene. Due to this risk, education regarding the importance of oral hygiene should be addressed for all individuals with dysphagia. Oral hygiene is not a stand-alone treatment for dysphagia; it is part of a larger, more extensive treatment regimen addressing all the anatomic and physiologic deficits.

Oral health is linked to oral hygiene. Specifically, good oral hygiene leads to improved overall health and a reduced risk of aspiration pneumonia (Muller, 2015). Conversely, there is an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia with poor oral health or oral hygiene. Due to this risk, education regarding the importance of oral hygiene should be addressed for all individuals with dysphagia. Oral hygiene is not a stand-alone treatment for dysphagia; it is part of a larger, more extensive treatment regimen addressing all the anatomic and physiologic deficits.

Clinical Note

Cultural and socioeconomic considerations should be part of treatment. Consideration should be given to norms for a given individual or family unit. There should be an ethnographic interview regarding oral care. This knowledge will provide a framework from which to present and train oral hygiene recommendations.

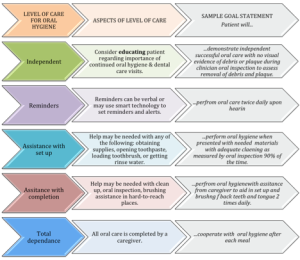

For many individuals, good oral hygiene is already part of their daily routine. These individuals may simply require education regarding the importance of continued oral hygiene and consistent dental visits. Oral health and the routine use of oral hygiene may be neglected in some populations, such as acute care patients, individuals of advanced age or isolation, or developmentally or intellectually disabled individuals. If oral care is neglected, this may lead to a greater volume of plaque and pathogenic bacteria (Barnes, 2014). For these individuals, oral care routines may be a function of their level of independence, current cognitive function, visual skills, hand strength, coordination, and manual dexterity. Box 4.9 delineates levels of dependence for oral care and provides sample treatment goals for each level of dependence. When an individual does not have good oral hygiene, or a recent change in medical status has resulted in a reduced ability to perform oral hygiene, treatment should address the need for good oral hygiene and provide the level of training required to achieve that treatment goal. When independent oral hygiene routines cannot be established, a caregiver may be trained in the oral hygiene regimen.

Box 4.9: Levels of dependence for oral care

Clinical Note

If help is needed in training oral care for a patient with adequate motor and cognitive function, an OT can be consulted to teach independent tooth brushing and flossing.

Clinical Note

Individuals who wear dentures should be remove dentures while sleeping. Dentures increase bacterial build-up, and thereby increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia (Iinuma, et al., 2014). Consider this when counseling patients and training caregivers in oral hygiene.

As indicated in Box 4.9, treatment aimed at improving oral hygiene may range from education regarding the risks and benefits of varying levels of oral hygiene to training caregivers when total dependence is needed for adequate oral care. Oral hygiene treatment may focus on the quality or frequency of the hygiene program. For patients with dysphagia, an increased number of oral hygiene routines should be encouraged to include before and after each meal. If the patient is at risk for aspiration during a meal, then oral hygiene before the meal may reduce the pathogenic bacteria contained in any aspirated material. Further, removal of food particles immediately after meals will reduce the bacterial build up reducing the risks after mealtime. Box 4.10 provides sample long and short term goals associated with oral hygiene. Appendix 4.1 provides a sample oral hygiene procedure including materials.

Box 4.10: Sample goals for oral hygiene treatment

Broad Goal: Improve safety of oral intake

Long Term Goal: Patient will reduce risk of aspiration pneumonia through improved oral hygiene by comparing pre and post oral hygiene after education/training of oral care routine.

Short Term Objectives:

- Patient will describe oral hygiene principles after being taught by the clinician with 80% accuracy.

- Patient will independently demonstrate proper teeth brushing after being taught by the clinician. Teeth cleaning will be considered successful if the oral cavity is free of residue, and both lingual and buccal surfaces of teeth in all four quadrants have reduced plaque upon visual inspection.

Clinical Note

After stroke, patients may have unilateral neglect, which means that they may need some structured reminder system to incorporate both sides of the oral cavity into their oral hygiene routine. This is particularly true with right hemisphere stroke.

Clinical Note

According to Clayton (2012), a patient who is status post stroke should have their oral cavity moistened at least every 4 hours and their teeth or dentures brushed at least twice daily.

The success of oral hygiene rests not only on the routine aspects of the hygiene regimen, but is a function of oral saliva. Saliva helps reduce bacterial overload in the oral cavity and provides a mechanism for removal of pathogenic bacteria. For patients with poor saliva production, even a good oral hygiene program may be insufficient to overcome the bacterial load imposed by reduced oral saliva (Yoon & Steele, 2007). In fact, individuals with dysphagia who take medication that causes dry mouth, are more at risk for bacterial build up in the oral cavity than their well-salivated peers. Further, poor oral care can lead to deterioration of oral membranes, thus increasing the incidence of xerostomia.

Clinical Note

Oral hygiene is assessed during the evaluation. The dysphagia clinician notes residue in the oral cavity or a level of halitosis, both of which may imply inadequacies of the current oral hygiene routine. Advanced tooth decay or poor condition of dentures may indicate inadequate oral hygiene long term.

Clinical Note

Patients being treated for head and neck cancer may have all their teeth removed if teeth are in poor condition and radiation will impact the oral saliva production. This is done preemptively to avoid chronic oral infections.

Free Water Protocol

Although not a direct treatment, free water protocols may be employed to reduce the risk of dehydration for individuals with dysphagia. The concept was first introduced in the literature as the Frazier free water protocol due to the location of its inception, Frazier Rehabilitation Hospital. Historically, it was developed as an alternative for patients who required the use of thickened liquids for safe liquid intake, yet had poor adherence due to dislike of the taste or texture of the thickened beverages resulting in an increased risk of dehydration. Simply described, it allows for patients with dysphagia who have good cognition and oral hygiene, as well as healthy lungs, to have access to freely drink unthickened water between meals. Hence, the name, free water protocol. Individuals who have increased safety with compensatory postures or maneuvers, should continue to utilize the compensatory supports during the free water intake. Free water protocols may be a standard part of an institution’s culture, or may be recommended and initiated by the SLP to promote an alternative for hydration. Free water protocols may use ice chips instead of water if clear and consistent aspiration is observed with thin liquids or larger bolus sizes.

It is hypothesized that individuals with reasonably healthy lung function and good oral hygiene, who aspirate on small amounts of water, will have limited medical consequences. The neutral pH of water allows it to be easily absorbed in the healthy lung if the water is not laden with oral bacteria or particulate matter left over from mealtimes. The caveat is that water is not available to the patient during or immediately after mealtimes. Consistent and thorough oral hygiene is required after each meal and may include brushing the teeth, wiping the oral pockets, suctioning up or removing any liquid or particulate matter that the patient cannot adequately remove, and completing the routine with a rinse and wipe of the oral cavity. Patients should receive adequate education regarding the reasoning behind the use of the free water protocol and the consequences of poor adherence to oral hygiene. Supervision may be required, especially in the first trials of the protocol.

Clinical Note

Free water protocols allow individuals to drink unthickened water between meals using the following protocol points.

- Typically the individual waits 30 minutes after mealtime before they can begin drinking water.

- Oral care must be completed before water is consumed.

- Continue use of required compensatory strategies.

- Some include a swish and spit prior to each water intake.

This protocol can be used for any individual with dysphagia who is at risk for dehydration. It may not be appropriate for individuals with dysphagia who also have impulsive behavior, lung disease or fragile lungs, excessive penetration and aspiration with thin liquid despite compensatory approaches, or reduced cognitive function. Individuals with neurologic degenerative disease may be at higher risk for developing lung complications or aspiration pneumonia as a result of a free water protocol (Karagiannis, Chivers, & Karagiannis, 2011). Also, individuals with declining oral health including obvious teeth decay, or poor oral care are not appropriate candidates for this protocol.

When compared to thickened liquids, use of a free water protocol has been linked to higher levels of oral intake (Garon, Engle & Ormiston, 1997; Karagiannis & Karagiannis, 2014; Karagiannis et al., 2011) and reduced UTIs (Murray, Doeltgen, Miller & Scholten, 2016). Further, in studies that compared the use of a free water protocol to a control group, there was no increase in incidence of aspiration pneumonia when individuals were compliant with the free water protocol (Pooyania, Vandurme, Daun & Buchel, 2015; Bernard, Loeslie & Rabatin, 2016, Murray et al., 2016). Free water protocol use has also been linked to a higher quality of life for individuals with dysphagia (Carlaw et al., 2012, Garon, Engle & Ormiston, 1997).

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is the use of a visual, auditory or tactile signal to reflect an internal physiologic event. It is used as a teaching tool to support understanding and manipulation of otherwise unfelt events. The hypothesis is that when patients better understand the desired output and can gauge their manipulation of the physiology through the use of biofeedback, therapy goals will be achieved in a more efficient fashion. In dysphagia therapy, biofeedback can be used as an adjunct to any compensatory or rehabilitative swallow treatment to (a) improve patient understanding of the desired output for swallow skill training, (b) improve training compliance, or (c) gauge resistance for improved strength training. Biofeedback can be performed using a variety of biological signals including pressure, palpation, muscle activation, visual imaging, or airflow. Box 4.11 lists some of the common forms of biofeedback used in dysphagia treatment.

Box 4.11: Commonly used biofeedback signals and their potential use in swallow treatment.

- Submental EMG to provide information on muscle activation

- Manual palpation as a gross estimate for hyo-laryngeal trajectory

- Airflow as an estimate of swallow-related apnea

- Pressure to note strength, or timing and duration of peak function

- FEES to provide information regarding pharyngeal compression, pharyngeal residue, etc.

Electromyography

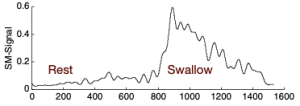

Electromyography is a measure of electrical potentials from muscles. An electrode is used to measure the potentials in a region. Electrodes can be inserted into a specific muscle or placed directly on the skin in the region of a muscle(s) of interest. Of these, the surface skin electrodes provide a non-invasive method for monitoring muscles near the surface. Submental surface EMG reflects the muscle activation of the floor of mouth muscles (Palmer, Luschei, Jaffe & McCulloch, 1999). During swallowing, this muscle activation is linked to hyo-laryngeal trajectory, which in turn may predict UES opening.As demonstrated in Box 4.12, changes in the electrical signal from the resting baseline indicate activity. Using this biofeedback approach, patients can be asked to monitor the height (reflecting strength) of the swallow, or the time or duration of the swallow. Submental surface EMG has been successfully used as an adjunct to swallow treatment in individuals with dysphagia from stroke (Bogaardt, Grolman, & Fokkens, 2009; Crary, Mann, Groher, & Helseth, 2004; Archer, 2014) and head and neck cancer (Crary et al., 2004).

Box 4.12: Smoothed tracing of an electrical signal from the submental surface

Note the increase in recorded electrical activity during the swallow.

Pressure

Intraoral pressure is commonly measured with an orally-placed air-filled bulb that is connected to an external pressure transducer. For biofeedback purposes, the devise provides a visual display of the degree of pressure imparted onto the oral bulb. Similar to the submental EMG, this technique can be used to enhance skill training (e.g., effortful swallow) and oral strength training (eg., Robbins, et al., 2007). The external link in Box 4.13 provides a schematic of the pressure bulb in the oral cavity. When the bulb is pressed, the changes in pressure are reflected in the LED display.

Box 4.13 External Link: Image of LED lighting used to reflect pressure on the bulb.

Click to see video of IOPI pressure bulb in oral cavity