Infant Swallow Physiology

Infant Swallow Physiology

Swallowing begins in utero as early as 11 weeks (Miller, Sonies, & Macedonia, 2003). Early suckle patterns are observed as early as 18 weeks and well established by 34 weeks in utero. By 38 weeks gestation (at time of birth), healthy, term infants swallow at least half their amniotic fluid per day (approximately 400ml) (De Vries, Visser, & Prechtl, 1982). (See Box 1.32 for a YouTube video of an in-utero infant sucking as recorded from ultrasound.) This bodes well, as it provides the sucking and swallow practice needed for a newborn infant who will swallow about that same amount per day during the first couple weeks of life.

Box 1.32 External Link

Feeding is essential for adequate growth, especially in the newborn. Growth can be monitored by the use of growth charts. Standardized growth charts have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and are available for download (Box 1.33). Feeding is considered “functional” if weight gain is consistently sufficient as noted by charting and monitoring the growth curve.

Box 1.33 External Link

“Want more?”

Growth charts have been developed by the CDC as well as WHO. Read this for an overview of these two growth chart sets.

Clinical Note

A feeding therapist may monitor growth using growth curves. Particular concern with appropriate referral should be considered if an infant drops from one growth curve to another. E.g., from 20th percentile to 10th percentile.

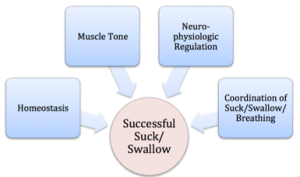

Over the first two years of development, as depicted in Box 1.34, successful feeding correlates with (1) the infant’s medical health and stability yielding appropriate developmental milestones, (2) intact neurophysiology, (3) the ability to regulate state regardless of environmental stresses, and (4) the ability to coordinate breathing into the suck-swallow skill that was practiced in-utero. Further, successful feeding is based on communication between the feeder and the infant. The feeder must learn to observe and respect cues from the infant regarding feeding readiness. (The video in Box 1.35 displays an example of feeding readiness in a healthy 3 month old infant.) The infant should be awake, quiet, and content during feeding. However, the infant may exhibit fussiness or crying just prior to feeding that is extinguished with the onset of feeding.

Examples Box 1.34: Feeding readiness in a healthy infant

Box 1.35 Video: Feeding readiness in a healthy infant

Once feeding is initiated, infants may cue the feeder that they need a break or that they are finished with their meal. For example, if an infant looks away during feeding they may be cueing the feeder that they have completed their feeding. Careful consideration must be given to the infant who pauses during feeding, yet retains eye contact. They may need a break, but may not have completed their feeding. When signs of stress are observed the feeder must be prepared to respond accordingly to the cues. Common stress cues are included in the Box 1.36.

Box 1.36: Infant stress cues

For some infants, the environment may also play a role in feeding success. The healthy, term infant should be able to age-appropriately process their environment. When the environment is overwhelming for the infant, it can have a negative impact on the feeding.

Clinical Note

Healthy term infants typically do not have difficulty with processing their environment. However, preterm infants or infants with medical issues may be reactive to environmental stress to such a degree that it interferes with, or derails, feeding success. Examples of environmental stress include light and noise.

Clinical Note

There are two age considerations when performing an infant feeding evaluation. First, the age of the infant is used to anticipate expected swallow milestones, especially during the first year when swallow milestones progress quickly. Second the gestational age at birth provides insight into the amount of in utero practice the baby received. Preterm infants have less in utero suck-swallow practice. When that in utero practice time is abbreviated, biological age should be adjusted to make up for the missing practice. For example, if a baby is 1 month premature, then at the chronological age of 2 months, we would evaluate them as if they were a 1 month old infant.

Oral Reflexes

Reflexes are involuntary response patterns to a specific stimuli. Some of the key primitive infant oral reflexes are presented Box 1.37. The healthy, term infant is born with intact oral reflexes to help facilitate food-seeking for successful feeding. The emergence of these reflexes is observed in utero and can be assessed during the infant feeding evaluation. Box 1.38 and 1.39 show reflexes as measured in healthy infants.

Box 1.37: Infant Oral Reflexes

Box 1.38 Video: Oral reflexes in a healthy 3 week old infant

Box 1.39 Video: Oral reflexes in a healthy 3 month old infant

Watch video here:

The gag reflex emerges in utero and is present throughout the lifespan. It is stimulated by touching the posterior tongue or palate and may result in tongue, head, and jaw protrusions, and pharyngeal contractions. The strength of the gag response may change with age. It is mediated primarily by CN IX and X, with potential additional contributions from CN V; CN IX is responsible for the sensory aspect of the gag, whereas CN X is responsible for the motor aspect of the pharyngeal response, and CN V is responsible for the motor aspect of the soft palate response. The presence or absence of the gag reflex is not an indicator of success with sucking or swallowing. In infants the presence or absence of the reflex can be noted. However, when the reflex is assessed in cognitively intact adults, an attempt should be made to differentiate between the sensory and motor contributions.

The tongue protrusion reflex is stimulated by touching the anterior tongue. It will result in tongue protrusion. This is evident at birth and typically fades by six months of age. The tongue transverse reflex is stimulated by touching the tongue and lips, with a result of the tongue turning to the locus of stimulation. This is seen in utero at about 28 weeks and fades by nine months of age. Both of these reflexes are mediated by CN XII.

When pressure is placed on the gums, the phasic bite reflex will yield a rhythmic closing and opening of the jaw. This reflex emerges around 28 weeks gestation and fades by one year of age. Touching the corners of the mouth such that the head turns to the side of the stimulus is called the rooting reflex. This emerges at about 32 weeks gestation and fades by about six months.

The sucking reflex is observed in utero and serves as a source of practice of this oral motor skill to prepare the infant for oral intake after birth. It can be stimulated with contact near or on the lips or with pressure on the gums. Preterm babies will show a weak or immature suck due to the lack of in utero practice. Although the reflex fades by about 4 months of age, infants continue to produce a voluntary suck.

Clinical Note

Absence of reflexes that should be present, or presence of reflexes that should have diminished, may indicate a central nervous system issue.

As you can see from a review of these basic infant reflexes, the newborn is reflexively prepared to eat. Collectively these reflexes help the newborn locate a food source, compress the food source to extract it, and reject or eliminate food when the system deems the input unsafe to swallow.

Respiration

Respiration at rest is easily achieved by healthy term infants. However, although the newborn infant had considerable practice with sucking and swallowing in utero, this occurred without respiratory interface. At birth the baby must coordinate the respiratory system with the sucking and swallowing skills. Respiration and swallowing behave in a coordinated, interdependent fashion using shared neural circuitry, peripheral muscles and structures. This means that when a pharyngeal swallow occurs, respiration is halted. This period of no respiration is referred to as deglutitive apnea or swallow-related respiratory cessation (Hanlon et al., 1997).

Of importance is the timing of respiratory cessation with respect to the phase of respiration. A respiratory cycle is made up of the inhalation and exhalation of air. The swallow, and therefore the timing of the respiratory cessation, can occur in either of these phases of respiration, as well as the cusp between the phases (Selley, Ellis, Flack, & Brooks, 1990). The timing of the coordination between swallowing and respiration has a developmental timeline before reaching a stable adult pattern. In the first 2 days of life, an infant may show large variability in the pattern– swallowing sometimes during inspiration, sometimes during expiration, and sometimes in between the phases. By day 3, most infants have a clear pattern; in most cases (approximately 69%), infants use a pattern with expiration after the swallow. A small level of variability in this pattern remains over the first year, with most infants using the predominant adult pattern– expiration after the respiratory cessation (Kelly, Huckabee, Jones, & Frampton, 2007).

Nutritive Sucking

Infants can engage in either nutritive or nonnutritive sucking. Nutritive sucking is used during feeding. Nonnutritive sucking is used for state regulation, pacification, and exploration of the immediate environment. The two are compared in Box 1.40.

Box 1.40: Nutritive versus non-nutritive suck

As noted above, newborn infants are born with reflexes that support their ability to suck, swallow, and locate food. At the time of birth, the nutritive suck is immature and is referred to as a suckle pattern. Stroking the tip of the tongue or front of the lip will stimulate this pattern which contains back and forward motion of the tongue (rhythmic licking motion) with loosely approximated lips. There may be leakage of milk from the corners of the mouth. As motor skills and body tone improve, suckle skills evolve into a mature and strong suck. This includes up-and-down motions of the tongue and jaw with firm approximation of the lips.

Clinical Note

Respiratory deficits (anatomical or physiological) may reduce swallow safety. E.g., Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).

Clinical Note

Newborn infants are obligate nose breathers. When they have a stuffy nose, it impacts feeding (Trabalon & Schaal, 2012).

Sucking takes advantage of pressure changes in the oral cavity. As the jaw moves up and down, the volume of the oral cavity changes. Negative pressure builds up when the jaw is in an open position (large volume in oral cavity), and draws fluid from the nipple. Positive pressure increases when the jaw and gum line compress down on the back of the nipple, squeezing fluid from the nipple. Thus, fluid moves from the nipple to the oral cavity due to pressure changes generated by the rhythmic movement of the oral structures.

Typically a nutritive suck averages anywhere from 1 to 3 sucks per swallow. That is, the liquid is sucked into the oral space for up to 3 sucks before a swallow is triggered. (See Box 1.41 for a sample VFES of healthy infant sucking.) The high position of the larynx and hyoid provide close approximation of the epiglottis and velum. In the case of a 2:1 or 3:1 suck-to-swallow ratio, the vallecula pocket can provide a safe waiting space for the liquid while the infant completes its sucking. During this sucking process, nasal breathing still occurs. When the liquid is swallowed, respiration briefly ceases (deglutitive apnea). For comparison, a non-nutritive suck is less vigorous and has six or more sucks per swallow.

Box 1.41 External Link

Video of infant swallow as visualized on VFES

Or read the full article online at https://www.nature.com/gimo/contents/pt1/full/gimo17.html

“Want more?”

Write stuff here

Check out these articles for more information on the development of the suck from an immature pattern to a mature pattern.

Development of Body Tone & Postural Abilities

Swallow development is linked, to some degree, to the physical development of the infant. At birth the infant is relatively hypotonic. Hypotonicity decreases over the first four months of life. By the third or fourth month, the infant begins to show more voluntary actions that oppose gravity, such as reaching with the hand, supported sitting, and bringing the hands to the mouth. Around 9 months you will see independent sitting, and perhaps sufficient tone to pull to a standing position. As body tone and motor function changes, feeding positions progress from a supported reclined position, to an independent upright position. Further, changes in body tone advance the independence of feeding as the infant progresses from a hand on the bottle or breast, to holding a spoon and independently drinking from a cup. By age 3, children are sitting at the table and using smaller versions of adult eating equipment–spoon, fork, open top cup, etc. See Box 1.42 for a sample of tone assessment in a healthy 3 month old infant.

Box 1.42 Video: Body tone in a healthy 3 month old infant

Taste Reception

Taste receptors develop in utero. Thus, infants begin to experience taste in the “flavor” of amniotic fluid, which can be altered with maternal oral intake. Tastes and preferences continue to evolve throughout life.

Video

Just for Fun

Baby tastes peas