Clinical Swallow Evaluation

Evaluation Overview

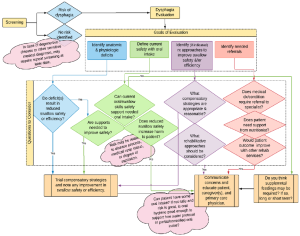

The dysphagia evaluation sets out to confirm the presence of dysphagia, define the anatomic and/or physiologic dysfunction associated with dysphagia, determine the current level of safety associated with oral intake and the variables that reduce or increase swallow safety, and clarify the variables that reduce swallow efficiency. Guided by this knowledge, the clinician identifies compensatory strategies that can be employed to immediately improve swallow safety and efficiency, if needed, and inform the appropriateness and choice of rehabilitative treatment approaches (Box 3.6). If this is an end-of-life evaluation, then the goal switches to providing suggestions that will promote safety and comfort without significant burden on the patient or caregiver.

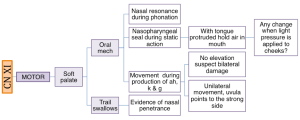

Box 3.6: Evaluation overview flowchart

Administration of the dysphagia evaluation may include a combination of clinical and instrumental approaches. The basic components include gathering a case history, a clinical exam of oropharyngeal function and swallowing, and perhaps an instrumental examination of the swallow mechanism. The history gathering may include a review of the medical chart, if available, as well as an interview with the patient and/or caregiver. Based on the information received from the referral, the dysphagia clinician may choose to schedule an instrumental exam without first completing a clinical exam. However, this does not negate the need for obtaining history or performing a clinical inspection of the oral cavity.

Clinical Note

For inpatients, the nursing staff should be interviewed to obtain their observations and concerns related to swallow function.

Some facilities have a defined procedure and protocol for a dysphagia evaluation. Generally, the dysphagia evaluation begins by providing the patient with an overview of the evaluation, and ends by providing a summary of findings and recommendations, including needed education to enhance understanding and implications of the results. There is variability across facilities and clinicians regarding the other components included. The components selected for inclusion in the initial evaluation may be influenced by the information received in the initial referral, patient or physician preference, patient age or medical condition, or the resources available to the treating clinician. Regardless, the examination should include history gathering, as well as clinical and/or instrumental diagnostic procedures best suited to the patient. The evaluation may also include education regarding the swallow deficit and any compensatory and rehabilitative treatment recommendations, and appropriate referrals. The outcome should be a clearer understanding of the deviant swallow pattern(s) so that the treatment choices are well guided.

The diagnostic process allows the clinician to generate and test a list of differential diagnoses, and evolve a clinical hypothesis. If the consultation includes adequate information such as medical history related to dysphagia, including signs and symptoms of the dysphagia, then the SLP may begin the evaluation with a list of potential swallow deficits. From this, a clinical hypothesis may be developed. In this case, the evaluation will be molded to address the concerns and the suspected causes as voiced in the clinical hypothesis. However, at times the consult may simply say, “Please evaluate Mr. Z for dysphagia” or “Mr. Z is at risk for dysphagia as evidenced by physician concern,” rendering a rather vague hypothesis. In these scenarios, the list of potential swallow deficits are all-inclusive. The goal is to develop a list of suspected swallow deficits which are based on the history obtained from the consultation, the medical record, and the patient or caregiver interview. Through the diagnostic process, the clinician collects data points (from clinical or instrumental probes) that help support or negate entries on the problem list. Thus, the evaluation should serve to solidify the clinical picture and support a clear assessment.

Impact of Patient Age

The age of the individual provides a framework of expected motor and swallow skills. In the case of preterm infants, an age adjustment should be performed. In-utero maturation prepares the infant to successfully participate in feeding. Preterm infants are robbed of the benefits of maturation, as well as time needed for sufficient in-utero swallow practice. Without adequate in-utero practice, the preterm infant is at a disadvantage for successful feeding when compared to full term peers of the same chronological age. Therefore, when working on feeding and swallowing skills in preterm infants, an adjusted age is calculated and used for age-appropriate peer comparison.

Clinical Note

Example pediatric age adjustment:

(chronological age – (40 – weeks LMP at birth))= adjusted age

The example below shows the adjusted age for an infant born at 30 weeks LMP whose chronological age is 12 weeks at time of evaluation. Infant should be compared to peers that are 2 weeks old.

(12 weeks -(40 weeks-30 weeks))= 2 weeks swallow safety.

On the other end of the spectrum, the geriatric population may exhibit presbyphagia (swallowing deficits related to aging). The dysphagia clinician must be aware of age-related changes that result in reduced swallow capabilities. This allows the clinician to tease out presbyphagia from the clinical picture and differentiate age-related changes from true dysphagia. For example, it is not uncommon to have a lower trigger site with a longer delay and an increased incidence of penetration in the elderly (>80 years old). This knowledge changes the clinician’s sensitivity to delayed trigger and incidence of penetration.

Clinical Note

Individuals may report that swallow deficits are amplified at certain times during the day or during certain routines. The clinician may wish to assess a patient’s swallow function during anticipated times of maximal deficit or best swallow performance.

Impact of Timing

While the timing of the evaluation may be relegated to an overlap in availability of the patient and clinician, some consideration should be given to time-related variables that may influence swallow performance. These may include the timing of the evaluation with respect to medical events, medication schedules, sleep -wake cycles, and hunger. For example, performing an extensive evaluation on a patient who suffered a stroke the day before may lead to an overestimation of the deficit, as an acute neurologic event may be followed by rapid change in performance. For patients on a medication regimen, the timing of the evaluation with respect to peak medication effect may need to be considered.

Individual schedules should also be taken into consideration. Sleep and wake cycles and level of hunger (based on usual meal times) may impact compliance and should be considered, particularly when evaluating infants, toddlers, and geriatric individuals. For example, predictable nap times should be avoided when scheduling an evaluation. For individuals who have limited attention or experience fatigue or medication effects, scheduling should respect daily routine with consideration for the time that promotes the best performance.

Use of Supports

When preparing for an evaluation, be aware of supports needed to successfully complete the evaluation. These supports may include eyeglasses, dentures, hearing aids, physical supports, such as special chairs or bolsters to help support them while sitting, or feeding supports, such as adaptive eating equipment. Performing an evaluation without typically-used supports may lead to an overestimation of the swallow deficits. If the patient uses feeding supports such as adaptive eating equipment, then these may need to be evaluated for their continued usefulness.

Impact of Setting

Location of the dysphagia evaluation may be an acute care hospital, rehabilitation hospital, long term care facility, outpatient facility, or home. Location of evaluation or level of patient care needed may influence the evaluation procedure. For example, in the acute care setting, level of illness or medical stability may dictate the time allotted for the evaluation, as well as the location of the evaluation. Some acute care patients may have limited mobility or require extensive monitoring, further influencing the evaluation location and duration. Further, in acute care, other health professionals may also need to perform an evaluation. Therefore, members of the health care team may be competing for patient evaluation time, necessitating the need to prioritize the various consults. On the positive side, however, is the fact that in the acute care setting, the dysphagia clinician will have access to medical records and caregivers. Further, if instrumental exams are warranted, the dysphagia clinician can easily and quickly performed a bedside clinical evaluation.

In long term care facilities, an individual who is scheduled to receive various therapies or evaluations per day, will require a time manager. Many facilities dictate specific times for meals, medication distribution, and social events. Therefore, evaluations (and treatment sessions) should be schedule with respect for other community events and activities.

For home bound individuals, an outpatient evaluation appointment requires access to transportation which may be limited to specific times of the day or days of the weeks. In an outpatient clinic setting, the patient may experience stress associated with attending the evaluation. For example, it may be difficult to get a ride to the evaluation or a patient may need to miss work. It is also possible that the patient is concerned about the actual evaluation–why they were referred or the problem(s) that resulted in referral. Clinicians can ease patient stress by being mindful of these possible concerns and explaining the purpose and procedures of the evaluation.

Clinical Note

In an acute care setting the clinical evaluation may be brief as the patient may not be ready for trial feeding or may fatigue quickly. Daily checks my be incorporated to assess changes in patient readiness for oral trials or instrumental exam.

Patient Report & Quality of Life Measures

In some facilities, particularly outpatient clinics, individuals may be asked to complete questionnaires prior to the initial evaluation meeting or while in the waiting room. Questionnaires can be geared toward a description of the problem and associated symptoms, or quality of life estimates. Facility-developed history forms can be complimented with currently available checklists and self-assessment tools. Self-assessment provides insight into the patient’s understanding of the swallow deficit, as well as the impact of this deficit on the primary stakeholder— the person who has the swallow deficit. Box 3.7 gives a summary of some of the currently available tools for this task. These completed questionnaires, along with any knowledge obtained from the consult or medical record, can serve to guide the clinical interview.

Clinical Note

There are some quality of life (QOL) instruments that provide health related QOL specific to a disease process such as:

- Head and neck cancer (HNCa)

- MD Anderson QOL

- UW QOL

- Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 39

- Swallowing Outcome After Laryngectomy (SOAL)

- Neuro QOL

- Reflux Symptom Index

Box 3.7: Instruments used to measure patient-reported swallow function and quality of life

| Instrument | Description |

|

44-item swallow-related quality of life measure divided into 9 sections yielding 10 domains (burden, desire and duration, symptoms, food selection, communication, fear, mental health, social, and fatigue). Each item is scored from 1 (always) to 5 (never). Scores from items from each section or domain are summed. A higher score means better swallow-related quality of life. |

|

|

10-item swallow-related health status instrument that includes brief questions regarding symptoms, social, duration, and mental health. Each item is scored 0 (never) to 4 (always). The score of all items are summed. A higher score (max 40) is greater dysfunction; >3 indicates concern. |

|

|

20 items divided into 3 domains (emotional, functional, physical). Each item is scored 1(strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). A higher score (max 100) means better function. |

|

|

17-item swallow-related functional health status questionnaire that focuses largely on symptoms and briefly addresses mental health and eating duration. Each item is scored on a continuous 100mm visual analog scale line from never to always, which are summed to get a total score. A higher score (max 1700mm) means greater dysfunction. |

|

|

20-item swallow-related questionnaire that is divided into questions about swallow function, physical symptoms, and emotional symptoms relative to the swallow deficit. Each item is scored 1 (normal) to 7 (severe). A total score as well functional, physical, and emotional subscores are calculated and compared to the normative database. A higher number is associated with a more severe perceived dysfunction. |

|

|

12-item questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer , where each question has from 3 to 6 response options that are scaled evenly from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Scores are divided into 2 sub-scores –physical score and social/emotional score. |

*Click on titles for external links to the questionnaires.

Activity

Activity 3.1 Identifying starter questions

- Open the completed SWAL-QOL

- Review and score the responses

- Guided by the expressed concerns of the patient, identify 5 starter questions for your ethnographic interview

Cognitive Function

It is important to estimate the cognitive capabilities of the patient. This understanding will help you frame your questions to make them grammatically and semantically accessible to the patient. Although cognitive assessment is not the focus of this text, level of alertness and cognitive status may not only impact your ability to gather information, but it may also impact swallow function (Leder, Suiter, & Warner, 2009). Cognitive status and orientation can be assessed informally by engaging the patient in conversation and observing their abilities to appropriately interact and respond. During this interaction, the clinician can identify the patient’s ability to follow commands, and monitor and control their own behavior. If the clinician deems the individual an adequate historian, the history gathering and clinical exam can proceed as planned. If the patient has limited cognitive abilities, information can be obtained from caregivers, or communication supports can be provided as needed.

Clinical Note

For a brief formal cognitive evaluation try the Mini Mental Status Exam or the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.

For an informal assessment, you can ask general orienting questions. For example: What is your name? Where are you? What is the year? Who is the current president? You may also give simple 1 and 2 step commands.

For example:

- Please hand me the cup.

- Can you please put the cup down and show me your ID band?

Patient History & Current Status

History gathering is an essential element to the clinical exam. A thorough history allows you to generate a list of suspected swallow problems and formulate a logical and unifying hypothesis regarding the swallow disorder with respect to the noted signs and symptoms. When a standardized evaluation approach is not used, a clear history and the resulting clinical hypothesis can serve as a guide to direct the clinician in the selection of diagnostic probes and procedures.

Clinical Note

Chart review red flags that may trigger a dysphagia evaluation.

- History of aspiration pneumonia

- History of neurologic event (stroke, degenerative disease, etc…)

- History of intubation

- Prolonged meal times

- Recent weight loss

- History of surgery in head and neck region

- History of respiratory illness

History may be obtained formally or informally. Formal history gathering is achieved by communicating with the referral source, performing a medical chart review, if the chart is available, or by interviewing the patient and/or caregiver(s). Information history gathering is obtained by observing the patient from the moment of contact. Observations of speech intelligibly and vocal quality can provide insight into general oral and pharyngeal function. General speed and fluidity of gross motor function, as well as postural stability, may provide insight into motor control, and trunk support during mealtimes. The patient’s chief complaint, history of the problem, and the informal observations made during the interview provide essential data for understanding the individual with dysphagia.

Clinical Note

Sample starter questions:

- Tell me what brings you here today.

- What is your understanding of the purpose for this evaluation? (Do you know why you were referred to me?)

- Tell me about your swallow problem.

- Tell me about when this problem started.

- What else was going on when this problem started?

- What do you think is causing your swallow problem?

- Tell me about how the swallow problem has changed since you first noticed it.

- What happens when you try to swallow?

- What food/liquid/situation/triggers makes it worse/better?

- How have your eating habits changed?

- What else would you like me to know about your swallowing?

The goals of the history gathering is to confirm the reason for consultation, to identify signs and symptoms of dysphagia, or medical diagnoses that are consistent with a risk for dysphagia, and to aid in the formulation of a swallow-related clinical hypothesis to better define the evaluation approach, as well as needed referrals. While gathering history, the clinician should ascertain the individual’s primary concern(s) and their goal(s) for this evaluation. Specifically, history gathering should include current medical status, dysphagia symptoms, patient complaint, past medical history, current medications, patient cognition and compliance, and family and social history.

Clinical Note

Be careful not to confuse ethnographic interviewing with motivational interviewing. The primary goal in ethnographic interviewing is to identify the key concerns of the patient. In motivational interviewing you are seeking commitment to change and aiding the patient in exploring their commitment to treatment.

“Want more?”

Sample ethnographic clinical interview.

Clinician: Tell me about your swallow problem.

Patient: I have a hard time swallowing. Sometimes I cough, especially at dinner time.

Clinician: What do you typically eat during dinner?

Notice how the clinician extended the discussion of the difficulty associated with dinner. Once that is explored, the clinician may want to inquire about the other meals. What is a typical breakfast? How does breakfast differ from dinner?

Clinical Note

Good interview technique employs an ethnographic approach. This means that you do not use a standard set of questions, but rather use the patient content to drive the next interview questions. Sample questions for ethnographic interview may include the following:

- Please tell me more about that.

- What do you mean when you say, (quote their words)?

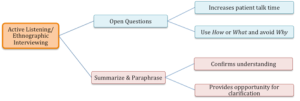

Although there are specific areas that need to be addressed and specific questions that the clinician may want to ask, there are techniques such as ethnographic interviewing which is an active listening approach that can be employed to maximize the success of the clinical interview. This technique is summarized in Box 3.8. In this approach, a checklist of questions may be useful as a starting point. Future questions are guided by the responses to the initial question. Efficiently gathering an adequate history involves asking guided and discriminating open questions that can only be formulated from listening to the patient. The initial question should be broad in nature, such as “Tell me about your swallowing.” (See Box 3.9 for example.) Questions should be open ended in order to elicit more than a one-word response. Keep the conversation free of complex grammatical structures and medical jargon. Reflect the terminology and level of language used by the patient and caregiver(s). At various points the clinician should summarize information to ensure understanding and provide an opportunity for clarification. This level of listening allows the clinician to formulate the next question. Through the process, the clinician can loop back as needed to be sure that all information is acquired. This process allows the patient to report what they think is important and the clinician to obtain the information they need. From this technique, the clinician may also obtain new insight into the swallow problem and be better informed of what treatment will provide the greatest impact for the individual. (See sample history note sheet in Appendix 3.1)

Box 3.8: Overview of interview techniques

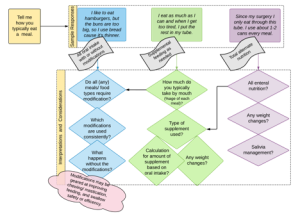

Box 3.9: Example of how responses can drive the interview

While an extensive interview may yield a more focused understanding of the problem leading to a more comprehensive clinical hypothesis, in the current medical climate, where contact time per patient is used as a metric for success, some facilities do not provide sufficient time to perform comprehensive history gathering. It is possible that history gathering is performed simultaneously with the evaluation probes.

Chief Dysphagia Complaint

Asking the patient to describe the swallow problem clarifies their understanding of the deficit. The description of the swallow deficit should include an overview of the problem, the onset of the deficit (gradual or sudden), the timeline of the deficit (no change since onset, continuous decline), consistency of the deficit (always there vs. comes and goes), what happens when they swallow (reported signs of dysphagia), and what makes the deficit better or worse (consistencies, postures, time of day). As the patient is sharing their complaint, the dysphagia clinician should highlight the signs and symptoms, and continue developing and revising the swallow problem list. Aspects not covered in the patient response can serve as questions in the continued interview.

If the patient-defined cause of the swallow deficit does not line up with the current clinical hypothesis, the dysphagia clinician may need to modify the clinical hypothesis to incorporate patient insight, or consider that the cause identified by the patient may be inaccurate. Consider, for example, a patient who suffers a stroke, causing her poor-fitting dentures to enter into her pharynx. The patient reports that the cause of the dysphagia is a side effect of the dentures entering the pharynx, and not a result of the stroke. She is certain that once the throat injury incurred by the dentures is healed, her swallowing will return to normal. Regardless of the accuracy of the patient-reported cause of the swallow deficit, the dysphagia clinician should address this cause.

Current Oral Intake & Nutrition Status

If not addressed in the consult, medical record review, or chief complaint, the dysphagia clinician should explore how nutrients are being received. If the patient takes all food and liquid orally, inquire about the use of any supports such as postures, alterations to food consistency, or food choices. If the patient does not take all nutrients orally, then inquire about the type and amount of alternate nutrition.

If weight history was not revealed in the previous interaction, the clinician should ask about unintentional weight loss. If the patient is uncertain about changes in weight, inquire about changes in the way their clothes fit or changes in their belt position. Box 3.10 shows a observational sign of weigh loss by noting the wear lines on an old belt. For pediatric patients, ask about the frequency and duration of meal times and any obvious levels of distress during meal times. A verbal diary of typical oral intake can help identify if intake is adequate or if a nutritional consult is needed. For adults, consider weight or body mass index (BMI); for infants and toddlers, review any changes in the child’s percentile on their growth curve.

Box 3.10: Weight loss observation

“Want more?”

Click here for an online BMI Calculator

Clinical Note

Sample questions for nutrition status:

- Tell me about what you eat and drink in a typical day.

- Tell me how you eat your food.

- Describe what you do to help yourself have a safe meal.

- What kind of physical activity do you do in a typical week?

- What changes have you noticed in your weight or in the way your clothes fit?

- Tell me how your eating habits have changed.

“Want more?”

BMI can be distorted due to its dependance on total weight. As muscle weighs more than fat, muscle builders will often be miscategorized as obese.

Medical Status

Current medical status may be obtained from the medical record review or from patient/caregiver interview. For inpatients, the medical record may report severity scores that reflect the general health and risk associated with the patient’s particular medical problem list. The medical problem list should be reviewed to evaluate the relationship between any illness or condition and the presenting dysphagia. If present, severity scores may provide an estimate of the patient’s ability to improve swallow function, and the risk associated with feeding an individual. The type of severity score used will depend on the system(s) at risk. A list of commonly used severity scores by medical professionals is included in Box 3.11. When possible, links to the scoring systems are included. Note that it is NOT within the scope of practice for the speech-language pathologist to perform these work-ups. However, in a chart review this information may provide an idea of how fragile the patient is and what risks may be acceptable.

Box 3.11: Commonly-used medical scales and measures

|

Commonly-Used Measures |

EXTERNAL LINKS |

|

|

Pneumonia |

|

http://www.mdcalc.com/curb-65-severity-score-community-acquired-pneumonia/ |

|

Heart Disease |

|

http://www.emoryhealthcare.org/heart-failure/learn-about-heart-failure/stages-classification.html |

|

Stroke |

|

http://www.mdcalc.com/atria-bleeding-risk-score/ http://www.mdcalc.com/abcd2-score-for-tia/ http://www.mdcalc.com/dragon-score-post-tpa-stroke-outcome/ http://www.mdcalc.com/hunt-and-hess-classification-of-subarachnoid-hemorrhage-sah/ |

|

Respiratory Disease |

|

http://www.aafp.org/afp/2014/0301/p359.html http://www.mdcalc.com/estimatedexpected-peak-expiratory-flow-peak-flow/ http://www.mdcalc.com/risk-score-for-asthma-exacerbation-rse/ |

|

Weight-Related Measures |

|

|

|

Degree of Illness & General Mortality Estimates |

|

http://www.mdcalc.com/apache-ii-score/ http://www.mdcalc.com/national-early-warning-score-news/ http://www.mdcalc.com/modified-early-warning-score-mews-clinical-deterioration/ |

The clinician should take into account the likely contribution of the current medical diagnosis and current medications to the swallow deficit. Specific medical diagnoses may be associated with predictable anatomic and physiologic alterations to the swallow. Some medications alter saliva production, motor function, or level of alertness, all of which may impact swallow function.

Clinical Note

Sample questions for medical history:

- Tell me about your health.

- Tell me about the medications and vitamins you take in a typical day.

- Tell me about any difficulty you have with mobility/activity/ breathing.

- Tell me about any medical tests that you have had lately.

Lab Values

During a review of the medical record, review recent lab values, if available. Although there is no 1:1 correspondence between lab values and dysphagia, some lab values are sensitive to dehydration or protein storage, and therefore, may help identify risk of dehydration or malnutrition, both of which may be a function of dysphagia. When these values are outside the acceptable range of normal, the dysphagia clinician may use this information to support a clinical hypothesis. For example, the patient reports not drinking liquids to avoid choking, and lab values support dehydration. The key lab values of interest to the dysphagia clinician are albumin, pre-albumin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), BUN:creatinine ratio, and total white blood count (Mills & Ashford, 2008). Also, as lab values may be linked to cognitive function, some consideration may be given to markers that reflect cognitive function such as hematocrit. Potential implications of lab values when they are outside the normal range are discussed in Box 3.12.

Clinical Note

IV placement can lead to over-hydration which may alter lab values; lab values may also be altered by kidney function.

Box 3.12: Lab values and dysphagia

Albumin and pre-albumin are measures of protein storage. Decreased protein stores can be an indicator of malnourishment (Collins, 2001; Crary et al., 2013). Yet, multiple variables, including dehydration, may influence the outcome rendering these biomarkers inconsistent reflections of nutrition status (Banh, 2006; Bernstein, Kreutzer, & Steffen, 2016). In general, albumin reflects long-term protein storage with a half-life of 12 to 21 days. When protein intake is reduced, the impact may not be immediately observed in albumin levels. However, a consistent reduction in protein should be measurable within 3 to 4 weeks. Conversely, when protein intake is restored, albumin should recover within approximately 2 to 3 weeks.

Pre-albumin has a half-life of 2 to 3 days reflecting short-term protein storage. Pre-albumin levels will typically begin to decline in the first week of change in protein intake, and will begin to recover within two days of protein supplementation. Due to the quick response time to changes in nutrition status, prealbumin is a better biomarker than albumin for recent diet changes. However, because it quickly recovers once protein stores are increased, pre-albumin is only useful if noted before nutritional supplements are initiated. Pre-albumin is less sensitive to changes in hydration.

Patients with dysphagia are more at risk for dehydration; increased BUN or BUN:creatinine ratio may indicate dehydration (Crary et al., 2013). Evidence of dehydration may also be found in reduced capillary refill, poor skin turgor, increased resting pulse rate, abnormal blood pressure, or general lethargy.

White blood cells fight infection or inflammation. Total white blood cell count reflects a person’s ability to fight an infection. An elevated white blood cell count may indicate a current or recent infection or inflammatory process. While many things can increase white blood cell count, aspiration resulting in a low-grade pneumonia is certainly on the list.

“Want more?”

To learn more about lab values check out these websites:

Current Respiratory Status

Poor respiratory status can negatively alter swallow timing, thus increasing the risk of aspiration as well as the physiologic response to aspiration. Therefore, it is important to note current respiratory issues. In general, internal physiologic systems are biased to make sure that the blood is well oxygenated. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other diseases of respiratory compromise can result in reduced oxygenation of the blood. Rather than risk deoxygenation of the blood and, consequently, tissue and organs, the physiology will be biased toward maintaining oxygenation despite the request from the swallow pattern generator to transiently turn off the respiratory system to allow for a safe swallow. Thus, to maintain needed levels of oxygenation, respiratory cessation may be shortened, altering the timing of swallow events. The shortened duration of respiratory cessation may increase the risk of aspiration. If aspiration does occur in a lung that is already compromised, there may be a further reduction in oxygenation abilities.

The presence of supplemental oxygen, a tracheostomy tube, or mechanical ventilation may imply a respiratory disease. Yet, even when a tracheostomy tube is used in the absence of pulmonary disease, as may be the case with temporary airway edema status post surgical procedure, the respiratory system is altered and this can impact swallow function. At the very least, by placing a subglottal leak in the system, the pressure bias that provided protection of the airway is now lacking. When a tracheostomy tube is present, it is important to identify the level of glottal function and the type of tracheostomy tube (cuffed or uncuffed). Unless a patient requires a closed system for ventilation, a cuffed tracheostomy tube should be deflated before eating or drinking.

Clinical Note

For patients with a cuffed tracheostomy tube that is not deflated during oral intake, swallow related laryngeal trajectory may: (1) be reduced by the drag of the cuff on the trachea and (2) over time, cause break down along the tracheal wall.

Clinical Note

It is NOT true that an inflated cuff protects a person from aspiration and its consequences. In fact, if aspirated food stays atop the inflated cuff, it may increase bacterial load when it finally enters the lungs.

Clinical Note

When performing trial swallows on a patient with a cuffed tracheostomy tube, consider having a respiratory therapist assist in suctioning and deflating the cuff before beginning the trials.

The dysphagia clinician may inquire about any respiratory tests (e.g., spirometry or chest x-ray) that have been performed with the recent hospital admission or medical diagnosis, or as a function of the swallow deficit. Spirometry provides information about the overall health of the lung. A chest x-ray may provide support of aspiration if infiltrates are noted in the lungs. In aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis, infiltrates are typically localized, and the location may be a function of the patient’s position during eating or resting. If a patient eats in a reclined position, infiltrates are typically located in the posterior aspect of the upper lobe and the superior segment of the lower lobe. If aspiration occurs in an upright position, infiltrates are usually located in the right middle or lower lobe (Kim, Lee, Lee, & Bae, 2008). The radiology report should provide information on the location of the infiltrates, as well as the age of the infiltrates (chronic vs. acute).

Family & Social Status

The presence of dysphagia can alter family and social interaction, as individuals may be embarrassed or lack confidence to continue with their previous activities. As this may greatly impact quality of life, it is important to identify what social supports are in place and how dysphagia may impact the social interaction of an individual. Further, the cultural background or religious affiliation of an individual may indicate the extent that the dysphagia may have on his/her family and spiritual life. The clinician must be mindful of the cultural or religious background of the patient, as there may be rules or desires associated with food intake.

Clinical Note

Sample starter questions for family & social status:

- Tell me about your living situation.

- Tell me about your job.

- Give me an example of when your swallow problem interferes with your family or social activities.

Past Medical History

Past medical and surgical history are important aspects of the history as they provide insight into the current swallow deficits. A history of a specific medical diagnosis or medical procedure may implicate a particular swallow deficit. It is important to inquire about the: (1) past history of major illnesses (recurrent pneumonia), medical diagnoses (e.g., COPD, DM) or medical procedures (e.g., tracheotomy, use of ventilator), (2) surgeries performed in the head and neck area, (3) radiation treatment to the head and neck area, (4) GI issues, (5) respiratory issues and intubation history, and (6) past oral-motor, speech, or dental issues. For pediatric patients, also inquire about the timeline of developmental milestones with respect to both gross and fine motor development, as well as feeding milestones.

As you are reviewing the medical record consider any previously-performed medical diagnostic exams that might be of interest to current swallowing status. For example, consults from neurology, gastrointestinal, ENT, or radiology procedures that involved the head, neck or esophagus, may provide insight into current swallow status.

The Evaluation Debate: Clinical vs. Instrumental Approaches

Once the history is clear, the clinician will perform probes and/or procedures to further evaluate and quantify the swallow deficit. There is some debate regarding the best approach for a dysphagia evaluation — clinical probes or instrumental procedures. There are three aspects that fuel the debate. First, screening and clinical evaluation probes are sometimes used interchangeably, where the combined strength of screening procedures are used as evaluation measures. As the successful output of the clinical exam is based on the probes selected, when the exam is limited to screening probes, the output may be inadequate to develop a comprehensive clinical hypothesis. When the clinical evaluation is lacking in essential data points such as a detailed history or an oral motor exam (including muscles and cranial nerves of importance to mastication and swallowing), the clinical exam may be inadequate to provide a complete picture of the dysphagia. Second, there is a concern that even a complete and complex clinical exam does not include visualization of the pharyngeal events, and therefore, aspects of dysphagia, particularly silent aspiration, may be missed. Third, while complete and complex understanding of the dysphagia mechanisms are best elucidated with instrumental procedures, it comes at a higher cost and with greater risk to the patient. Therefore, when choosing to perform an instrumental exam, the risk:benefit ratio needs to be weighed.

There are times when the clinical exam may be deemed sufficient by the dysphagia clinician. Guided by a history that is not supportive of dysphagia, a negative clinical exam may indicate the end of the diagnostic need, or result in a referral to another specialty. In this case, the clinician must feel confident that there is limited to no risk of silent aspiration. The clinical exam provides only a gross estimation of hyo-laryngeal trajectory and risk of penetration or aspiration (Rangarathnam & McCullough, 2016). Therefore, the clinical exam alone can not definitively rule out aspiration and will not define aspects of pharyngeal and esophageal physiology. To provide optimal and efficient treatment of pharyngeal deficits, an instrumental exam is required.

While the dysphagia clinician chooses the diagnostic approach best suited for the individual and their swallow deficit, sometimes the choice is motivated by scheduling and availability of both the clinician and the patient, as well as wishes of the patient or the practice standards imposed by the payer (patient’s insurance provider).

Box 3.13 provides a comparison of the clinical and instrumental exam. This textbook will address both the clinical and instrumental approaches in the diagnosis of swallow disorders.

Box 3.13: Comparison of clinical and instrumental exams

Clinical Note

There are multiple approaches used to perform the clinical swallow exam. These are guided by patient need, service availability, and clinician experience. This is typically done using an informal approach that incorporates a collection of clinical probes. Formal testing is also available. There is currently only one formal validated instrument for a clinical swallow exam–The Mann Assessment of Swallow Ability (MASA).

Clinical Swallow Evaluation

The clinical examination of swallowing begins the moment you meet the patient. As you introduce yourself, you observe vocal quality, facial asymmetry, odd movement patterns, and gross motor skills including speed and symmetry of movement. For example, as a measure of gross motor function, the clinician can observe how long it takes for a patient to get up from the chair in the waiting room and the level of independence in their movement as they ambulate to the clinic room. You can speculate on cognitive skills by noting the patient’s responses to introductions, instructions, and questions. Overall articulation, speech, and voice may provide clues about oral motor function of the patient.

As with any clinical exam, the goal is to develop and support a clear conclusion based on the careful collection and interpretation of data. Box 3.14 provides a sample of clinical probes and how the information can help shape the clinical thought. A clinical evaluation differentiates itself from the screening process as it intends to do more than simply diagnose the risk or presence of a disease. That said, the clinical exam is limited and may be inadequate to provide a comprehensive understanding of the swallow physiology and resulting deficits.

Box 3.14: Sample clinical probes and their connection to swallowing

Clinical probes that explore swallow safety include:

- Trial Feeding or timed water swallow

- drop in O2 SATS

- coughing, or throat clearing

- change in vocal quality

- Respiratory measures

- reduced respiratory support may result in reduced duration of glottal closure and altered timing of glottal closure

- Phonation measures

- Any measures that implicate poor glottal valving may impact swallow safety

Clinical probes that explore swallow efficiency include:

- Trial Feeding or timed water swallow with manual palpation

- multiple swallows per bolus

- protracted oral movement before the swallow

- reduced swallow capacity

- Phonation measures

- chronic wet vocal quality may be associated with residue

Remember with swallowing, direct investigation of function is largely limited to the oral component; pharyngeal function is implied by clinical observation. In addition to defining the swallow pathophysiology, the clinical evaluation should begin to highlight treatment approaches that might be appropriate for the hypothesized swallow deficit. Brief trial treatment may be initiated during the evaluation to see if the patient is compliant and that the chosen treatment approaches are appropriate and useful for that patient and their hypothesized swallow deficit(s).

The clinical exam should include an oral mechanism exam, and may include a trial feeding (if appropriate), as well as trial compensatory strategies. Medical stability, cognition or attention may change as a function of fatigue, timing of medication use, and sleep-wake cycles. Consider the best time to perform the evaluation to assess optimal swallow abilities.

Weight

It is useful and reasonable for the dysphagia clinician to measure height and weight during the evaluation. To improve accuracy of weight change over time, make note of the weight of clothing as this may change with the seasons. In clinics where there is no access to a scale, a self-reported weight can be obtained and should be recorded as such. When available, measure percent body fat. If this is not available, BMI can be calculated by using the weight and height data. While BMI is easily distorted, it continues to be widely used. As body fat measures become more readily available in standard scales, clinicians can incorporate this data point into their evaluation.

When reporting weight, it is important to compare current weight to previous weights to note any changes in weight over time. This information may help the clinician identify a needed referral to a dietician or nutritionist, and may provide guidance for oral intake recommendations. Weight loss (or gain) should be calculated as a function of time. When rapid weight loss is identified over a short period of time (less than 6 months), ask the patient if they are: (1) aware of the weight loss, and (2) know why they experienced this weight loss. This will tease out causes unrelated to dysphagia, such as the recent death of a spouse who may have served a primary role in meal preparation.

Clinical Note

Percent weight change can be calculated as follows:

(Past weight-current weight)/ past weight) * 100

Remember to indicate the period of time over which the weight change occurred.

Oral/ Nasal/ Pharyngeal/ Laryngeal/ Respiratory Exam

The oral mechanism exam provides information on structure and function of the face and oral cavity. It also allows inference on the structure and function of the nasal, pharyngeal, laryngeal, and respiratory aspects. During a clinical swallowing evaluation, the oral mechanism exam should focus on the oropharyngeal sensory and motor functions, and respiratory supports needed to perform a safe and efficient swallow. When possible, task specificity should be employed in assessment of sensory and motor function. That is, mimic the sensory and motor tasks used in swallowing.

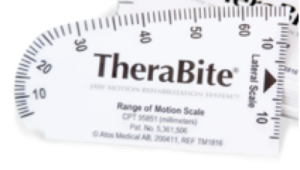

Before initiating the oral mechanism exam, assess the patient’s ability to follow instructions and open the mouth upon command. Inability to open the mouth may be a cognitive issue, but also may be related to limited oral opening capabilities that may occur with neurologic or structural events. If poor oral opening is observed, massaging the jaw may improve the extent of oral opening. Oral opening can be measured using an oral measuring device. (See sample in Box 3.15.) A goniometer can be used to quantify asymmetry and range (Box 3.16). If reduced oral opening is the result of a recent medical procedure, splinting or stretching protocols may be needed to improve oral opening. Severely impaired oral opening may limit the oral motor exam.

Box 3.15: Sample range of motion scale can be used to measure oral opening and other movements such as tongue lateralization

Box 3.16: Goniometer can be used to quantify symmetry of structures at rest and during movement

In young neurologically-involved patients a bite reflex may occur. If the oral opening is variable and related to a stimulus, as is the case with a bite reflex, the oral exam may be limited. The use of a bite block may allow some visual inspection. Note that patients with low cognitive function and a strong bite reflex may bite anything, including clinician fingers or metal spoons. Judgment should be used when performing a clinical exam on these patients.

Clinical Note

In cases where a measuring device is not available, oral opening can be assessed by asking an individual to see how many fingers they can fit in their mouth. On average, most people can fit 3 fingers in their oral opening.

Clinical Note

In some clinics, oral mechanism exams are done indirectly by observing the anatomy and physiology during an instrumental exam, such as a VFES or FEES.

General Observations

Brief visual inspection of the head, neck, and intraoral region may reveal concerns. During observation of the head and neck structures, note the presence of scars, asymmetry, and wasting or atrophy. Abnormal movement or tremors, tics, or fasciculation should be documented. Note obvious signs and symptoms that are indicative of risk for penetration or aspiration such as weak or breathy phonation, wet or gurgly vocal quality, coughing, oral residue, drooling (inability to swallow secretions) or dysarthria. In studies that compared signs and symptoms to level of dysphagia, dysarthria and slowed rate of speech correlated well with oral phase dysphagia (Martin & Corlew, 1990).

Altered body tone, either hypertonic or hypotonic, may impact swallow function. If a patient is hypotonic, unsupported sitting may be inadequate to use gravity assist for bolus flow. That is, their trunk or head may not be able to maintain an upright and consistent sitting position throughout a mealtime. This is particularly problematic when combined with poor airway protection. Hypertonicity or spasticity may alter timing of events due to slowed and jerky movement of individual swallow structures. Deficits in body tone are common in preterm infants and patients with neurologic insult or disease.

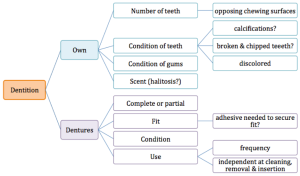

The daily oral care routine can impact oral health, as well as the risk for aspiration pneumonia. While indication of an unkempt oral cavity may be observed during the interview by noted halitosis, intraoral inspection will provide more detail of dentition status (own teeth, edentulous, wears dentures) and condition (level of decay or observable plaque). Box 3.17 provides an overview of the dental inspection. This inspection can be used to support the adequacy of the oral hygiene routine, the ability of the teeth to perform mastication, and the ability of the oral structures to direct and propel the bolus such that no particulate matter is left on the teeth or in the oral pockets. If a patient has their own dentition, the clinician should make note of the number and condition (presence of decay) of remaining teeth and the condition and color of the gums. If the patient wears dentures, observe the fit and condition. If dentures appear well positioned and stable and no adhesive has been used, apply lateral and anterior pressure to see if they are easily dislodged. Poorly fitted dentures may be related to denture size or insufficient gum ridge to stabilize and support dentures. Dentures can be removed and inspected to provide support for successful denture and oral care. Once the teeth are out of the mouth, inspect their condition and cleanliness. Look for gaps in the dentition to note if there is an adequate chewing surface on each side. Poor fitting dentures or dentures in poor condition may alter mastication and bolus control.

Box 3.17: Schematic overview of sample dentition inspection

Clinical Note

If intraoral visualization is reduced due to posterior tongue hump, ask the patient to breathe through their mouth and this may improve visibility.

Oral Reflexes

Checking the presence or absence of oral reflexes may be included in the swallow evaluation. When included, consider appropriateness of the presence or absence of various reflexes with respect to the age of the patient. Some reflexes are present throughout life, whereas others extinguish with maturation. Healthy reflexes that are present at an inappropriate age are considered abnormal. Previously extinguished reflexes may return with neurologic insult. Box 3.18 provides a sample of oral reflexes with potential assessment stimuli and responses. (Revisit infant oral reflexes in Chapter 1.)

Box 3.18: Assessment of reflexes

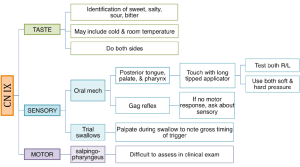

Palatal and pharyngeal (gag) reflexes can be tested during the swallow evaluation. The gag reflex has a response that involves the pharynx and the palate. A gag reflex is generally present at some level in most patients of any age. While the gag reflex is not essential for a healthy and safe swallow, it should be assessed to give an indication about the sensory and motor systems of that region. Historically, it was believed that an absent or impaired gag would result in aspiration. Yet, only 5% of individuals with an absent gag show evidence of aspiration on VFES (Leder, 1997). While absence of a gag is not predictive of the incidence of aspiration, a reduced or absent gag is associated with an increased risk of dysphagia. If no motor response is observed, inquire about sensory function, as mediated through CN IX.

To test the palatal reflex, hold down the tongue and stroke each side of the uvula or lightly tap the interface between the hard and soft palate at midline. A palatal elevation will be noted. When stroking the side of the uvula, you should see an elevation of the palate on the side that was stroked. There is some evidence that a cold probe may better elicit a response. However, this is not consistently supported in the literature (Bove, Månsson, Eliasson, 1998).

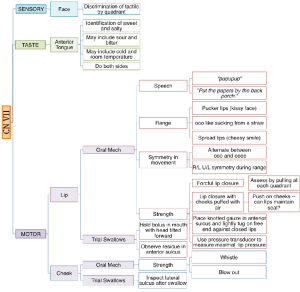

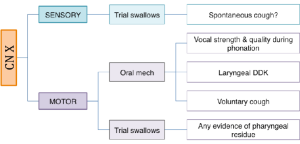

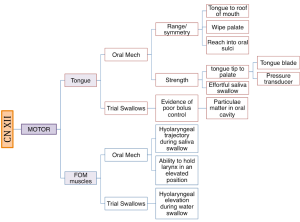

Cranial Nerve Exam / Sensory Motor Exam

The integrity of cranial nerves should be examined during the swallow evaluation and should include sensory, motor, and taste function. For swallow function cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, XI, and XII should be evaluated. Sensory function is evidenced by a quick and complete response to stimuli. Motor function is evaluated for strength, range, and symmetry of movement. Some clinicians incorporate additional measures including speed, power, and endurance, as these measures reflect the needed muscle function over the course of a mealtime. When possible, task specificity should be employed in assessment of sensory and motor function. For sensory and taste function consider the contact site of the typical bolus pathway. For motor function consider the bolus a resistive force. The cranial nerve exam should assess movement and strength in ways that mimic bolus control and propulsion. Unfortunately, not all structures and muscles can be easily tested against resistance in the non-instrumental clinical exam (e.g., pharyngeal constriction).

Boxes 3.19 through 3.24 provide a summary of oral motor exam probes that can be used to test the integrity of various cranial nerves and muscles. Note that the detailed information in these boxes is not covered in the same level of detail as the accompanying text. However, the clinician should be sufficiently familiar with ways to assess individual cranial nerves should the need arise. The extensive number of probes provided can be reduced to items that either reflect your concerns about the anatomy and physiology, or best mimic needed function for safe and efficient swallowing.

Box 3.19: Sample CN V probes

Box 3.20: Sample CN VII probes

Box 3.21: Sample CN XI probes

Box 3.22: Sample CN X probes

Box 3.23: Sample CN XI probes

Box 3.24: Sample CN XII probes

When assessing motor function, the clinician may provide modeling with or without a mirror so the patient can imitate the movement and use visual feedback for motor tasks a needed. This may facilitate a better outcome particularly in patients with reduced cognitive function or oral apraxia.

“Want more?”

Because the SLN splits into the internal and external branch where the external branch is motor for CT and the internal branch is sensory for the airway, it is possible to have a functional pitch glide and still have SLN damage that impacts sensory function.

If aspiration or premature spillage is suspected, motor function for mastication can be evaluated without food by using of gauze. A length of gauze, knotted on one end and dipped in a flavor, can serve as a pseudo-bolus and be used to simulate chewing. The free end of the gauze can be held and manipulated by the clinician and allow movement or removal of the bolus as needed.

While the oral mechanism exam is typically done with little technology, there are devices available to help quantify strength, endurance, power, and range of motion. Strength can be estimated by measuring the tongue-to-palate force against an air filled bulb, as is the case with the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument (IOPI). Power and endurance can be estimated from pressure by manipulating strength and time. For power, the patient is asked to reach a specific percentage of their maximal ability (typically 70%) as quickly as possible. For endurance, the patient is asked to hold a specific percentage of maximal ability (typically 50%) as long as possible.

While often estimated through visual inspection, range and symmetry of movement of some structures can be directly measured using specific oral measurement devices (as noted previously in Boxes 3.15 and 3.16) or a clear and flexible ruler. As postural strategies may be incorporated to enhance swallow safety, the dysphagia clinician may wish to assess truck control and head mobility for range of motion.

Laryngeal Function: The airway entrance (a.k.a. laryngeal aditus) opens into the pharynx and must be protected during the swallow. For a safe and efficient swallow, the larynx moves in a superior and anterior trajectory. This aids airway protection by moving the airway entrance away from the bolus flow pathway. Hyo-laryngeal trajectory also enhances down-folding of the epiglottis and UES opening. In addition to hyo-laryngeal trajectory, the internal diameter of the larynx goes to zero to prevent leakage of any penetrance into the airway. Assessment of laryngeal function is limited to clinical signs (i.e., no visualization) during the clinical exam. Clinical probes such as vocal quality, s:z ratio (the amount of time a person can hold an /s/ and /z/ phoneme), laryngeal diadochokinetics, effortful cough or throat clear, falsetto voice or pitch glides, and palpation during saliva swallow, can estimate glottal valving and hyo-laryngeal trajectory.

Clinical Note

The timing of a spontaneous cough during a clinical exam may have some physiologic relevance. A cough that occurs immediately with the swallow is more likely to be linked to aspiration than a cough that is delayed. A delayed cough is more likely to be linked to either pharyngeal residue or extra esophageal reflux.

A gross estimate of laryngeal function can be obtained by listening to vocal quality. A strong and clear voice indicates adequate glottal valving, which is needed for airway protection. Conversely, a breathy vocal quality may indicate an inability to adequately valve (close) the glottis. Inadequate valving, if present during the swallow, may allow for aspiration of laryngeal penetrance.

An s:z ratio provides a measure of respiration and laryngeal function, where the s duration reflects respiratory capacity for phonation and the z duration reflects phonatory capabilities. A mismatch in these durations (s>z) may reflect incomplete glottal closure. An s:z ratio greater than 1.4 has been linked to a space occupying lesion or reduced neural integrity, both of which can alter complete glottal valving, thus reducing airway protection during the swallow.

The strength or volume of a cough can provide an informal estimate of glottal contact and the ability to protect the airway. Ideally a spontaneous cough can be observed during the evaluation. If no spontaneous cough occurs, a voluntary cough can be produced on command. While a voluntary cough has been shown to be a good estimate of the ability to propel contents from the airway, the voluntary cough does not utilize the same neural circuitry as a spontaneous cough. A voluntary cough uses cortical input, whereas a spontaneous cough is reflexive and is mediated by the brainstem. However, if a spontaneous cough is not produced, then the clinician can evaluate the strength of the volitional cough. A weak cough may indicate reduced airway protection or reduced respiratory function.

The superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) provides important laryngeal sensory function, which aids in protection from penetration. This sensory function can be estimated with pitch tasks. Extreme changes in pitch require sophisticated interaction between the thyroarytenoid (TA) and cricothyroid (CT) muscles. These muscles represent different branches of the vagus nerve. The TA muscle is innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN); the CT muscle is innervated by the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN). Because the SLN innervates the CT muscle and the CT muscle is responsible for lengthening the vocal folds, a pitch glide task may provide gross evidence of the integrity of SLN. This probe may be used to confirm suspicions of silent aspiration. When manual palpation is applied to the neck, pitch glides can be used to assess laryngeal trajectory. Hyo-laryngeal trajectory can also be assessed by palpating the neck during a saliva or water swallow.

Laryngeal diadochokinetics can provide insight into laryngeal neural and muscle integrity. It can be produced using an adductory or abductory task. However, for swallow function, the adductory task is more important. In this task, the patient produces a rapid series of glottal sounds as quickly as they can while maintaining distinct productions. A timed set of productions are used to yield the number of productions per second. Reduced diadochokinetics highlight the potential for reduced motor innervation or muscle function of vocal fold adductors.

Clinical Note

Norms for laryngeal diadochokinetics are 2-3 productions per second in children, 4-6 in adults, and 3-5for individuals over age 65 (Ptacek, Sander, Maloney & Jackson, 1966; Maturo et al., 2012, Mack, 2015).

Respiratory Function: Respiratory dysfunction is not a predictor of dysphagia (Monteiro et al., 2014). Yet, respiratory function is indirectly important for an efficient and safe swallow. During the swallow the respiratory system, which shares circuitry with the swallow pattern generator, must be briefly extinguished (deglutitive respiratory cessation). If oxygen saturation is low or other respiratory issues are present, the patient may not be able to achieve adequate apnea duration to support the swallow timing. While the patient history may have already provided the needed information on respiratory status, several probes can be used to assess the respiratory system. These include breath holding, counting respiratory rate, or observation of rest breathing. A simple screen may be to ask the patient to hold their breath; if they can produce comfortable breath holding for at least three seconds without a drop in oxygen saturation their respiratory system should be able to achieve at least a single swallow without risk of respiratory distress.

Rest breathing patterns can be observed to note the work of breathing or nasal patency. If quiet respiration is effortful with noted movement in the torso and shoulders, there may be difficultly with repeated periods of deglutitive respiratory cessation, as is the case during meals. Further, if the resting respiratory rate is high, this indicates that oxygen saturation may be low. Thus, the patient may not be ready to attempt oral feedings. Respiratory rate can be measured by counting the number of respiratory cycles per minute. Location of air exit should also be observed. If an individual keeps their mouth open for breathing, there may be reduced nasal patency. While this may not impact oxygenation, if the nasal cavity is plugged and the oral cavity is the primary airway passage, this may interfere with the ability to adequately masticate and then swallow the bolus. Box 3.25 provides normative data for respiratory rate.

“Want more?”

Currently, Medicare will pay for home oxygen if oxygen saturations fall below 88%.

Box 3.25: Respiratory rate norms

Observation of a weak cough may indicate inadequate respiratory function. When peak cough flow goes below 270 liters/min, then the cough is unlikely to produce enough force to keep lungs clear during respiratory illness or with aspiration. Determination of strength can be judged clinically.

If respiratory concerns exist after the completion of the above probes, further exploration can be performed by measuring oxygen saturation, peak flow, or pulmonary function. Although pulmonary function tests are typically performed in the respiratory therapy department, some respiratory measures can be achieved in the speech-language pathology clinic. Pulmonary function tests may be used to judge appropriateness of oral feeds for patients at risk of aspiration. Various spirometry measures have been used to try and define risk and/or likelihood of aspiration and penetration. These measures include forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), cough volume acceleration (CVA), peak expiratory flow rise time (PEFRT), and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR).

Lung auscultation may be added to the evaluation and will require training to familiarize the clinician with the various lung sounds. It is beyond our scope of practice to diagnose lung maladies. However, the presence of secretions or stridor in the upper airway, or crackles or wheezes in the lung indicate the need for a medical referral. Upper airway secretions may be easily cleared by asking the patient to do a forceful throat clear. As a speech-language pathologist you simply need to note abnormal lung sounds or alterations to airflow.

Pulse oximetry, which is a measure of oxygen saturation in the arterial blood, can provide an estimate of lung health. The technology uses an infrared light to measure oxygen in the blood. Measuring oxygen saturation is a portable, inexpensive, and noninvasive approach. It can be achieved with minimal or no discomfort, and has no side effects. Further, there is no additional burden on the patient with this procedure. The amount of oxygen present in the blood and available for exchange at the tissue level is measured and expressed in percent saturation. If oxygen saturation is low, swallowing may be impacted. Normative values for oxygen saturation are simple; people should have saturations close to 100%. Altitude may alter oxygen saturation. At 1 mile above sea level (like Albuquerque or Denver) an adult averages 92% or higher; at sea level the average is closer to 94% or higher. Oxygen saturations above 88% in adults are considered acceptable.

Oxygen saturation may be impacted by age or lung health. In healthy preterm infants, saturations of 90% or higher should be expected; full term infants have oxygen saturations above 95%. Although oxygen saturations lower than 90% in infants may trigger concern, lower than 80% clearly impacts body functions as the organs are deprived of needed oxygen. For adults, when oxygen saturation is below some critical value (typically 88%), supplemental oxygen will be utilized. The bottom line is simple: if the body’s oxygen needs are not met, deglutitive respiratory cessation may be shortened, resulting in altered timing of swallow events.

Trial Feeding /Swallowing

Trial feeding should be used during the clinical examination in patients who are either already eating orally or have been deemed safe enough to perform feeding trials. In patients with severe dysphagia, it may be preferable to perform trial swallows with instrumentation. If an instrumental exam is planned, maintenance trial swallows may not be performed during the clinical exam. Clinical trials may involve ice chips, water swallows, or observation of specific foods or liquids. Boluses may vary by volume or consistency to assess ability of the mechanism to perform during mealtimes.

Clinical Note

If you are having difficulty locating the hyoid bone try placing your hand in line with the jaw bone and slide it to the neck. The hyoid bone is often near the region where your hand contacts the neck.

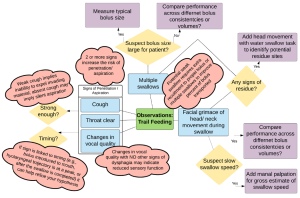

Observations during structured oral intake may reveal signs and symptoms of dysphagia and help in the development of the clinical hypothesis. (See Box 3.26 for sample observations.) Prior to actual oral intake, level of alertness should be noted to ensure that the individual is ready for the oral presentations. Body posture/position and postural control should be noted as position is a potential source of modification. Presence of impulsive behavior may warrant caution during trial swallows.

Box 3.26: Potential interpretation of clinical observations during trial feeding

During feeding and swallowing the clinician can observe gross management of food or liquid including self-feeding skills (if applicable), signs and symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia, and aberrant feeding or swallowing patterns, such as tongue thrust during swallow. Trials can begin with a saliva swallow, which may be challenging for patients with xerostomia. There is no standard protocol of trial swallows. The food or liquid used during trial feeding may differ depending on the age of the patient or the clinical questions being addressed. Boluses may vary by volume, consistency, and temperature. A comprehensive clinical exam will typically include liquid, solid and perhaps a puree or semi-soft consistency. Sample liquid trials include 5ml water, a typical bolus size of water, and perhaps a challenge size (larger than typical bolus size). These can be presented via cup or straw, taking note of the individual’s usual mode of liquid intake. Nectar or honey thick liquids may be presented by cup or spoon. A pudding or yogurt consistency is presented by spoon and therefore is typically between 3-5cc (depending on the spoon). In the case where special spoons are used (e.g., maroon spoon), the patient or caregiver is encouraged to bring the utensils to the clinical evaluation. Masticated items may include a cookie or cracker. When known consistencies or volumes are reported as difficult, the patient or caregiver is encouraged to bring the troublesome food or liquid so that the clinician can test it. For individuals who do not self-feed, the dysphagia clinician may wish to observe the feeding technique(s) used by the caregiver.

The clinician should document the amount, consistency and mode of presentation for each bolus, as well as the response to that bolus. General observations may include the level of assistance needed to perform the swallow, changes in head or body positioning during the swallow, and clinical signs of dysphagia, penetration or aspiration. Specific observations include coughing or choking during the swallow, grimacing, throat clearing, drooling, or if phonation is added before and after the swallow, a change in voice quality to a wet gurgly voice. Adding manual palpation, pulse oximetry and/or cervical auscultation during the trials can enhance the information from trial swallows.

Manual Palpation of Hyo-laryngeal Region

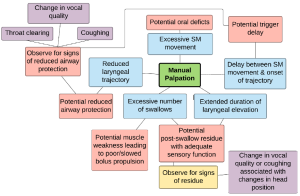

Manual palpation may be used as an adjunct to the clinical exam and aide in the understanding of pharyngeal physiology including a gross estimate of timing, potential sites of residue, or variations to swallow patterns, such as multiple swallows per bolus.

Procedure: Manual palpation, as the name suggests, is the placement of the clinician’s fingers on the patient’s neck while the patient swallows. Several finger placements have been discussed for manual palpation. In general, a single finger is placed at each of the following locations: submental region, hyoid region, and thyroid region (Box 3.27). The sensory input of the swallow on the lightly-placed fingers may be limited by glove use. Therefore, clinicians may choose to perform glove-free manual palpation. Of course, good hand washing should be performed before and after patient contact. Manual palpation may also be limited in unshaven males or individuals with excessive neck fat.

Box 3.27: Sample finger placement for manual palpation procedure

- Submental

- Hyoid bone

- Top of thyroid cartilage

- Bottom of thyroid cartilage / top of cricoid cartilage

The patient is asked to swallow while the clinician observes and feels the swallow. By feeling the swallow, the clinician obtains a gross estimate of the timing of the onset of tongue movement and the onset (or delay) of hyo-laryngeal elevation associated with the swallow. Struggles associated with swallow initiation can be felt with palpation. To enhance the information obtained from manual palpation, such that the clinician can gain insight into potential pharyngeal residue, the procedure noted in the schematic can be employed (Box 3.28). The procedure includes phonation and postural changes between swallows. Between each posture the individual is asked to phonate so the clinician can listen for changes in vocal quality, which may imply that there is bolus retention or laryngeal penetrance. Self-imposed compensatory strategies, such as the use of multiple swallows per bolus, can be assessed using manual palpation. Other compensatory strategies, such as the Mendelsohn or effortful swallow maneuvers, may be employed during the swallow trials to note immediate changes in signs associated with swallow safety. It should be noted that while some perceived changes may be palpated, there is no data to direct the connection between what we feel and swallow function. In other words, palpation of multiple swallows or increased duration of laryngeal elevation does not dictate improved bolus transit or clearance. (See Box 3.29 for sample clinical observations made during manual palpation.)

Box 3.28: Sample manual palpation procedure

Box 3.29: Potential interpretations of clinical observations made during manual palpation

Clinical Note

Multiple swallows per bolus are commonly observed in patients with either weak bolus transit or UES dysfunction. This self-initiated technique may imply a sensory perception of pharyngeal retention.

In addition to the described procedure, timing measures can be added. In a timed water swallow a measured amount of water is swallowed as quickly as comfortably possible. Using palpation, the clinician counts the number of swallows and the duration needed to ingest the full amount of water. Several data points can be calculated for comparison to norms— average number of swallows per second, average time per swallow, average amount (cc) swallowed per second (aka swallow capacity), and average amount (cc) per swallow. (See Box 3.30 for normative data.)

Box 3.30: Norms for timed water swallow of 50 ml water bolus (Hughes & Wiles, 1996)

Despite its frequent use in the clinical swallow exam, there is no evidence to support the effectiveness, validity, or reliability of manual palpation. In fact, some clinical profiles will be missed on manual palpation. For example, a patient with a sensory deficit where the bolus enters the pharynx without a delayed pharyngeal response, and perhaps even silent aspiration, and then finally a swallow, the delay may be received, but the detrimental and swallow risk will not be specified in this clinical exam. Therefore this technique should be used with caution.

Pulse Oximetry

Pulse Oximetry

The dysphagia clinician may use oxygen saturation as an estimate of safety for eligibility for trial feedings. Individuals whose oxygen saturation levels are below 85% should not receive trial feeding without the approval of the primary care physician, or, in the case of inpatients, the covering hospitalist or consulting pulmonologist. In the last decade oxygen saturation monitors have reduced in price, and as a result are easily available to the average consumer. While they are primarily used to indicate lung or respiratory issues, there is potential application for this technology as an adjunct to trial swallows. The theory is that direct aspiration of ingested material may cause a reduction of airflow to the occluded lung tissue. This can lead to a ventilation-perfusion mismatch (ratio of amount of air to the amount of blood reaching the alveoli), thus decreasing arterial blood oxygenation (Wang, Chang, Chen, & Hsiao, 2005).

Procedure: The procedure is simple. Oxygen saturation is monitoring prior to the swallow to establish baseline saturation and variability. A mean baseline is calculated. Oxygen saturations are then measured before, during, and immediately after swallowing, as well as 2 minutes after and 10 minutes after each consistency. The mean baseline is compared to the lowest saturation level obtained during and after the swallow. A drop in oxygen saturation that is greater than 2% from baseline may indicate aspiration (Collins & Bakheit, 1997; Colodny, 2000; Lim et al., 2001).

Evidence: There is limited and variable evidence regarding the usefulness of oxygen saturation measures for assessment of swallowing disorders. The procedure has been shown to be sensitive to the presence of aspiration in patients with healthy lungs under the age of 65 (Lim et al., 2001; Collins & Bakheit, 1997). Aspiration of larger quantities of food will likely produce greater and more clinically significant oxygen desaturation (Sherman Nisenboum, Jesberger, Morrow, & Jesberger, 1999). Yet, more recent evidence shows that the results of the procedure are not consistent and may only identify 40% of aspiration events (Ramsey, Smithard, & Kalra, 2006; Wang et al., 2005). While the efficacy of oxygen saturation as a sole diagnostic measurement is questionable, it is easy to use and inexpensive to both clinician and patient. In a clinical swallow exam, decreases in arterial oxygen saturation can be used as a marker for aspiration. However, if no change in oxygenation is observed, this does not mean that the patient is not aspirating.

Limitations: Theoretically, an aspiration event may have a transient impact on oxygen saturation. Yet, there are several limitations to this hypothesis. First, it is plausible that the instrumentation device used to measure oxygen saturation may impose a limitation on the accuracy and consistency of this methodology as a diagnostic tool for swallow disorders. Pulse oximeters may vary by precision and sensitivity. Newer and cheaper pulse oximeters may employ an averaging algorithm to report oxygen saturation. This algorithm may dilute the extreme values, obliterating the sensitivity of the device for measuring small and transient changes in oxygen saturation. Sample rates employed by the available devices may further impact the sensitivity of a given device to small changes in the level of oxygen saturation.

Second, oxygen saturation is typically performed without oro-pharyngeal visualization of bolus flow. In this scenario the relationship between drops in oxygen saturation and swallowing cannot be definitively linked to physiology. The assumption that aspiration may have occurred still does not aid in identification of a clear physiologic deficit, as aspiration can occur for multiple reasons before, during and after the swallow.

Finally, there are external factors that can influence the accuracy of oxygen saturation. These include the impact of nail discoloration, ambient environmental light, motion artifact, insufficient hemoglobin, and a poor peripheral pulse. Removing polish and cleaning the nail, eliminating sources of ambient light, and keeping motion artifact to a minimum may avert these aspects. For individuals with insufficient hemoglobin and a reduced peripheral pulse, this technique may be inadequate.

Cervical Auscultation

Cervical Auscultation