Impact of Anatomical & Physiologic Alterations on Swallow Function

Impact of Altered Oropharyngeal Anatomy

Surgery or trauma to the head and neck region may result in mechanical dysphagia. When this occurs, knowledge of the missing or altered structure(s) and its role in an efficient swallow, dictates the anticipated swallow deficit(s). Facial fractures, including fractures of the mandible or maxilla, may occur during motor vehicle accidents (Peltola, Koivkko, & Koskinen, 2014). While the swallow deficits associated with fractures are typically temporary, there may be long-term consequences. In the case of multiple fractures to the mandible or maxilla, there may be misalignment of teeth and alteration in the chewing surface after the fractures are healed. While the goal of surgery is to approximate the alignment of the teeth, this may not be identical to the alignment of the premorbid dentition. Still, these issues are often easily retrained or resolved with dental support.

Clinical Note

Consideration should be given to missing or altered anatomy with respect to completeness of the structure, strength output of the remaining structure, range of motion of any remaining structure, and the impact of the missing structure on neighboring or connected structures. Understanding the role that each structure plays in a safe and efficient swallow allows the dysphagia clinician to hypothesize on the impact of an altered structure on bolus transport and swallow safety.

The most common trauma-related anatomical alteration in the oral cavity is loss of dentition. Tooth loss may also occur as a result of advanced age, poor oral care, or a surgical or medical procedure. For example, teeth may be removed as a precautionary measure in patients with oral cancers who are scheduled to undergo radiation. When dentition is missing, there is obvious alteration in the bolus-reduction ability, which may be significant enough to require changes in diet. Missing dentition may also impact bolus manipulation and oral bolus containment.

“Want more?”

There is an area in the IPC muscle where the muscle layers are weak and prone to dehiscence. This spot has been referred to as Killian’s dehiscence, named for Dr. Killian, a German laryngologist in the early 20th century.

“Want more?”

Often teeth are removed prior to the initiation of high dose radiation to the oral cavity, the mandible or maxilla bones, or any of the oral secretion glands. This is because high doses of radiation can compromise saliva production and jaw structure. When these are compromised, even a person with adequate oral hygiene is at increased risk for teeth and gum disease. Attempts to remove the teeth during radiation treatment may result in osteoradionecrosis, which means that the irradiated bone can’t heal. Thus to reduce risk of oral disease or painful results post radiation, most or all teeth are removed prior to exposure to radiation.

Congenital alterations to oropharyngeal anatomy may impact feeding and swallow development, rendering swallow function inefficient. Box 2.23 lists a sample of congenital anatomical alterations to the oropharynx. When the jaw or tongue have a clinically relevant size alteration (either too big or too small), feeding may be negatively impacted with respect to latching ability and generation of suck. Severe anchoring of the tongue or lip may impact feeding. A shortened lip frenulum is more apt to impair latching, whereas a shortened tongue frenulum may impact sucking and oral pressure generation. The presence of clefting, depending on the extent and location, may impair feeding by changing the pressure generation needed for adequate sucking and altering the bolus pathway.

Box 2.23: Congenital anatomical alterations

- Clinically relevant alterations to jaw or tongue size

-

- small and retracted jaw (micrognathia)

- large jaw (macrognathia)

- Cleft lip and/or palate may impact feeding by impairing latching, sucking and swallowing, or interfering with obligate nose breathing

- Tongue tie (anklyglossia) or lip tie may alter the ability of infants to latch and extract adequate nutrition from the food source (breast or bottle)

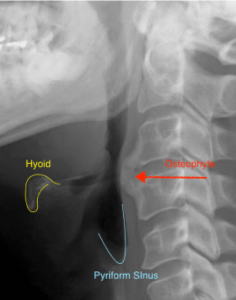

In addition to congenital anomalies or trauma-related alterations in anatomy, it is possible for anatomical structures to change throughout the lifespan (Box 2.24). Two common examples of age-related changes include osteophytes of the cervical spine (Box 2.25) and diverticulum in the pharynx (Box 2.26). An osteophyte, or bony spur, on the cervical spine is a common finding associated with aging. While they are typically thought to be asymptomatic, bolus transport may be impacted by a large osteophyte, or a well-placed small osteophyte, especially if it deflects bolus flow toward the laryngeal vestibule. Further, a large osteophyte may narrow the pharyngeal lumen (Egerter et al., 2015; Zhang, Ruan, He, Wen, & Yang, 2014). People with osteophytes may report a sensation of something in their throat during the swallow.

Box 2.24: Age-related anatomical alterations

- Loss of dentition

- Changes to cervical spine

- Diverticulum

- Osteophyte

- Ossification of cartilage

-

- Larynx

-

Box 2.25:Anterior cervical osteophyte

“Want more?”

Often teeth are removed prior to the initiation of high dose radiation to the oral cavity, the mandible or maxilla bones, or any of the oral secretion glands. This is because high doses of radiation can compromise saliva production and jaw structure. When these are compromised, even a person with adequate oral hygiene is at increased risk for teeth and gum disease. Attempts to remove the teeth during radiation treatment may result in osteoradionecrosis, which means that the irradiated bone can’t heal. Thus to reduce risk of oral disease or painful results post radiation, most or all teeth are removed prior to exposure to radiation.

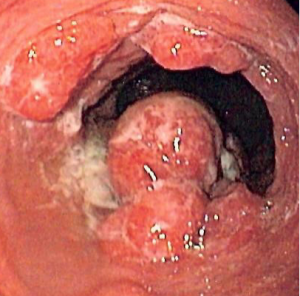

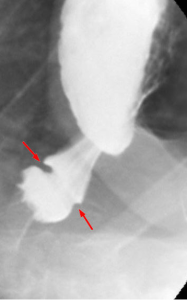

Diverticula are pockets that can occur throughout the body. In the pharynx or cervical esophagus, the most common site for pouching is in the inferior dehiscence of the pharynx resulting in a Zenker’s diverticulum (Box 2.26). It has been postulated that a Zenker’s diverticulum may occur with continuous exposure to high pressure at the site of Killian’s dehiscence in the inferior pharynx. Increased pharyngeal pressure is generated in the inferior pharynx when the CP muscle is either hypertonic, as may be the case with extra-esophageal reflux, or if its relaxation is not well-timed with other swallow events (Bergeron, Long, & Chhetri, 2013). Although a pharyngeal diverticula may not alter swallow function, regurgitation of undigested diverticular contents may occur after mealtimes. Regurgitated contents may be aspirated, putting the individual at risk for aspiration pneumonia.

Box 2.26 Video: Zenker’s diverticulum visualized during VFES

Altered Laryngeal Anatomy

The larynx, which sits anterior to and opens into the pharynx, must be moved and protected from the pathway of the bolus flow during the swallow. Alterations to the larynx may prompt deficits in airway protection, as well as alter the timing of airway protection or the length of deglutitive apnea.

Laryngomalacia is an anatomic abnormality where the cartilaginous framework lacks rigidity, thus the structure does not stay patent to support easy respiration. This is most often seen in infants and children, but is also noted in adults with sleep apnea (Revell & Clark, 2011; Gessler, Simko, & Greinwald, 2002). About 50% of children with laryngomalacia will exhibit swallow and/or feeding deficits (Simons et al., 2016).

Laryngeal clefts and tracheoesophageal fistulas (TEFs) are congenital anomalies that, depending on the extent, may result in communication between the trachea and the esophagus. Small laryngeal clefts may not greatly alter swallow function. However, large laryngeal clefts and TEFs may result in aspiration during the swallow by allowing passage of pharyngeal or esophageal content through the cleft or fistula into the airway.

“Want more?”

Learn more about laryngeal cleft classification by viewing the article Head and neck disorders affecting swallowing (McCulloch & Jaffe, 2006).

Impact of Altered Physiology

Physiologic events may be altered by changes in anatomy, strength, range of motion, neural drive, or timing. Anatomic impact on physiology is related to the extent of the anatomical alteration to the structure–complete or partial removal. Strength, range and timing of physiologic events may reduce safety or efficiency of swallow. For example, if lip strength is reduced, lip approximation may be inadequate or delayed resulting in anterior leakage of the bolus. Physiologic impairments may alter the speed or direction of the bolus flow pathway, or reduce the pressure imparted onto the bolus. Box 2.27 lists sample physiologic events and the potential negative impact on swallow function.

Box 2.27: Physiologic events and possible impact on swallow function

Esophageal Disorders

SLPs do not diagnose or treat esophageal disorders. However, understanding esophageal disorders and their potential impact on the oropharynx and swallow function is important. Further, understanding common terminology around esophageal disorders improves cross-professional communication. Disorders that involve the esophageal body can be subdivided into physiologic disorders that impact motility, structural disorders that obstruct the passage of the bolus through the esophagus, or functional disorders. Box 2.28 summarizes some common motility and structural changes to the esophagus.

Box 2.28: Esophageal disorders

| Motility | Structural Issues | Consequences of GERD |

|

Achalasia |

Diffuse Esophageal Spasm |

Esophageal Mass |

Esophageal Diverticulum |

Schatzki’s Ring |

Esophagitis |

Barrett’s Esophagus |

|

Failure to relax the LES |

Motility disorder with intermittent dysphagia |

Growth |

Pocketing along the esophagus |

Localized mucosal ring found at the end of the esophagus |

Reflux esophagitis |

Precancerous condition related to chronic GER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By Farnoosh Farrokhi, Michael F. Vaezi. (CC BY 2.0) |

© Nevit Dilmen [CC BY-SA 3.0 |

Permission to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 |

By Hellerhoff [CC BY-SA 3.0 |

By Hellerhoff [CC BY-SA 3.0 |

By Donald E. Mansell, MD [CC BY-SA 3.0 |

By Samir – taken from patient with permission to place in public domain, Copyrighted free use |

For more information and images on esophageal disorders visit: Liu, J.J. & Kahrilas, P.J. (2006). Pharyngeal and esophageal diverticula, rings and webs. DOI: 10.1038/gimo41 https://www.nature.com/gimo/contents/pt1/full/gimo41.html

Esophageal motility assists the transport of food from the upper to the lower esophagus. This distally traveling muscular contraction is paired with muscular relaxation in the immediately adjacent region. Disorders of esophageal motility may impact the swallowing of both liquids and solids, although complaint of solid food dysphagia is more common. For example, achalasia, a common motility disorder, is a dysfunction of the esophagus with failure to relax the LES. In this case, an x-ray of the distal end of the esophagus may show a bird beak appearance due to absent peristalsis.

Perhaps the most common esophageal dysfunction is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). This occurs from the backflow of food and stomach acid from the stomach, through the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) into the esophagus. This backflow may continue past the esophagus and penetrate through the UES putting the airway entrance at risk. Extra-esophageal reflux, or more specifically, laryngo-pharyngeal reflux (LPR) may result in disorders of voice and respiration if the gastric content makes its way into the larynx and below the glottis. Individuals with GERD may complain of non-cardiac chest pain associated with eating, or a lump in the throat (globus sensation) that may be momentarily relieved during the swallow. While GERD is linked to poor tone in the LES, about 50% of individuals with GERD also have esophageal motility issues (de Oliveira Lemme et al., 2005; Diener, Patti, Molena, Fisichella, & Way, 2001).

Summary

Dysphagia may result from alterations to anatomy or physiology. Understanding the common signs and symptoms of swallow disorders aids in appropriate referrals and may inform the dysphagia clinician of the best diagnostic approach, as well as treatment considerations.