15 On Persona and Tone in Poetry

On Persona

Is the speaker in a poem one and the same as the writer? Stop and consider this for a few moments. Can you think of any poems you have read where a writer has created a character, or persona, whose voice we hear when we read?

Wordsworth’s The Prelude was written as an autobiographical poem, but there are many instances where it is obvious that poet and persona are different. Charlotte Mew’s poem, ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ (1916) begins like this:

Three summers since I chose a maid,

Too young maybe – but more’s to do

At harvest-time than bide and woo.

When us was wed she turned afraid

Of love and me and all things human;(Warner, 1981, pp. 1–2)

Mew invents a male character here, and clearly separates herself as a writer from the voice in her poem. Some of the most well-known created characters – or personae – in poetry are Browning’s dramatic monologues.

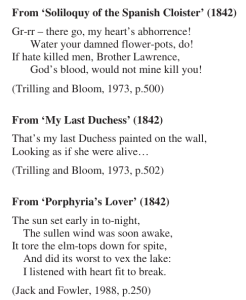

Consider the opening lines from three Browning poems. Who do you think is speaking?

Although the first speaker isn’t named, but we can infer that, like Brother Lawrence whom he hates, he’s a monk. The second must be a Duke since he refers to his ‘last Duchess’ and, if we read to the end of the third poem, we discover that the speaker is a man consumed with such jealousy that he strangles his beloved Porphyria with her own hair. Each of the poems is written in the first person (‘my heart’s abhorrence’; ‘That’s my last Duchess’; I listened with heart fit to break’). None of the characters Browning created in these poems bears any resemblance to him: the whole point of a dramatic monologue is the creation of a character who is most definitely not the poet. Charlotte Mew’s poem can be described in the same way.

On Tone

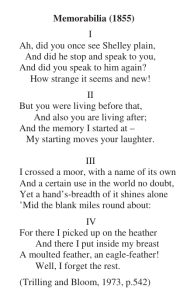

Let’s read one more poem by Robert Browning because it will help us consider a related feature of poem to persona: tone.

As you read this poem, consider: Who is speaking, and who is being addressed?

From the evidence of the poem we know that the speaker once walked across a moor, found an eagle’s feather, and has a high regard for the poet Shelley (1792–1822). The person being addressed is not named, but we discover that he (or she) once met Shelley, and this alone confers status by association. The word ‘you’ (‘your’ in one instance) is repeated in 6 out of the first 8 lines. ‘You’ becomes a rhyme word at the end of the second line, so when we reach the word ‘new’ in line four – one of the two lines in the first stanzas that doesn’t contain ‘you’ – the echo supplies the deficiency. ‘You’ clearly represents an important focus in the first half of the poem, but who exactly is ‘you’ ?

Thinking about this apparently straightforward question of who is being addressed takes us into an important area of critical debate: for each one of us who has just read the poem has, in one sense, become a person who not only knows who Shelley is (which may not necessarily be the case) but lived when he did, met him, listened to him, and indeed exchanged at least a couple of words with him. Each of us reads the poem as an individual, but the poem itself constructs a reader who is not identical to any of us. We are so used to adopting ‘reading’ roles dictated by texts like this that often we don’t even notice the way in which the text has manipulated us.

Now read the poem again, this time asking yourself if the speaking voice changes in the last two stanzas, and if the person who is being addressed remains the same.

If the first half of the poem is characterized by the repetition of ‘you’ and the sense of an audience that pronoun creates, then the second half seems quite different in content and tone. The speaker is trying to find a parallel in his experience to make sense of and explain his feeling of awe; the change of tone is subtle. Whereas someone is undoubtedly being addressed directly in the first stanza, in the third and fourth, readers overhear – as if the speaker is talking to himself.

At first the connection between the man who met Shelley and the memory of finding an eagle’s feather may not be obvious, but there is a point of comparison. As stanza 2 explains, part of the speaker’s sense of wonder stems from the fact that time did not stand still: ‘you were living before that, / And also you are living after’. The moor in stanza 3, like the listener, is anonymous – it has ‘a name of its own … no doubt’ – but where it is or what it is called is unimportant: only one ‘hand’s-breadth’ is memorable, the spot that ‘shines alone’ where the feather was found. The poem is about moments that stand out in our memories while the ordinary daily stuff of life fades. It also acknowledges that we don’t all value the same things.

There is an immediacy about the conversational opening of the poem which, I have suggested, deliberately moves into a more contemplative tone, possibly in the second stanza (think about it), but certainly by the third. We have considered some of the poetic techniques that Browning employs to convince us of the rarity of his find in the third and fourth stanzas. You might like to think more analytically about the word sounds, not just the rhyme but, for example, the repeated ‘ae’ sound in ‘breadth’ ‘heather’ ‘breast’ and ‘feather’. What, however, do you make of the tone of the last line? Try saying the last lines of each stanza out loud. Whether you can identify the meter with technical language or not is beside the point. The important thing is that ‘Well, I forget the rest’ sounds deliberately lame. After the intensity of two extraordinary memories, everything else pales into insignificance and, to reiterate this, the rhythm tails off. While the tone throughout is informal, the last remark is deliberately casual.

“8 Voice.” Approaching Poetry, The Open University, OpenLearn, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/literature/approaching-poetry/content-section-8.

Ringo, Heather, and Amar Kashyap. “Robert Browning’s Memorabilia.” Writing and Critical Thinking Through Literature, City College of San Francisco, LibreTexts, https://human.libretexts.org/Courses/City_College_of_San_Francisco/Writing_and_Critical_Thinking_Through_Literature_(Ringo_and_Kashyap)/12%3A_Writing_About_Literature/12.18%3A_Robert_Browning’s_Memorablia.