Chapter 11: Paragraph Development

Once you have the structure of your paper figured out, and the main idea you will support, you can start with the introduction and conclusion.

Not all people like to begin writing their introduction. Some writers like to begin the body paragraphs and then return to the introduction and conclusion once they know what it is they would like to focus on. There is no one right process. Find the process that works for you.

Introductions

When you are ready to write your introduction, there are multiple strategies available to help you craft a great first paragraph. Ideally the end of your first paragraph will clarify the thesis statement you will support in the rest of your paper. The video provides a quick overview of how to create an effective introduction.

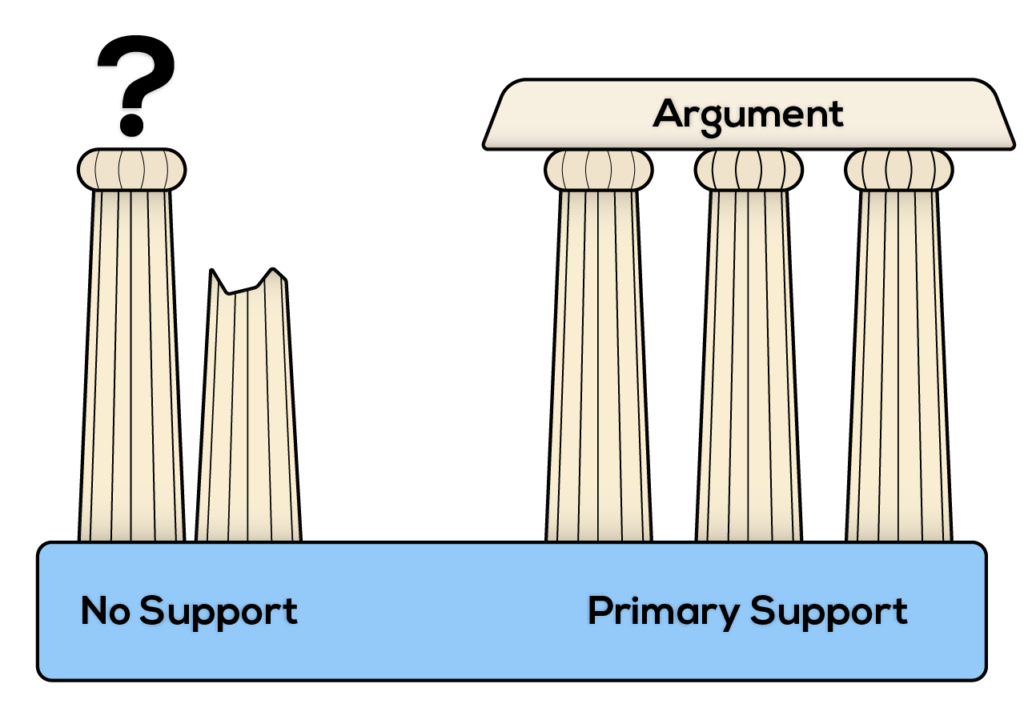

The following information from Successful Writing explains how to support your thesis statement within your body paragraphs. Without primary support, your argument may not be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on as you prove your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Identify the Characteristics of Strong Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of strong primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

-

Be specific. The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be specific. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

-

Be relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. This idea is so important, here it is again: effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

-

Be detailed. Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be overly detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Integrating Evidence

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

-

Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they cannot be disputed and help build your credibility. They support your stance by providing background information or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

-

Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

-

Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

-

Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about those experiences. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

Once you have your evidence organized, and the evidence relates to the points you have outlined for yourself, you have the scaffolding that you need to begin constructing strong body paragraphs. Now it’s time to begin constructing the building blocks that will help you create strong and developed body paragraphs.

Keep in mind that your evidence should compliment your ideas rather than overshadow them.

A chapter from Writing published by Boundless on the topic of writing effective paragraphs explains paragraph structure this way:

Topic Sentences

When you created your outline, you wrote your thesis statement and then all the claims you need to support it. Then you organized your research, finding the evidence to support each claim. You’ll be grateful to have done that sorting now that you’re ready to write your paragraphs. Each of these claims will become a topic sentence, and that sentence, along with the evidence supporting it, will become a paragraph in the body of the paper.

Paragraph Structure

While you’re writing, think of each paragraph as a self-contained portion of your argument. Each paragraph will begin by making a claim (your topic sentence) that connects back to your thesis. The body of the paragraph will present the evidence, reasoning, and conclusions that pertain to that claim. Usually, paragraphs will end by connecting their claim to the larger argument or by setting up the claim that the next paragraph will contain.

-

Topic sentence: summarizes the main idea of the paragraph; presents a claim that supports your thesis.

-

Supporting sentences: examples, details, and explanations that support the topic sentence (and claim).

-

Concluding sentence: gives the paragraph closure by relating the claim back to the topic sentence and thesis statement.

Paragraphs should be used to develop one idea at a time. If you have several ideas and claims to address, you may be tempted to combine related claims into the same paragraph. Don’t do it! Combining different points in the same paragraph will divide your reader’s attention and dilute your argument. If you have too many claims, choose the strongest ones to expand into paragraphs, or research the counterarguments to see which of your claims speak most powerfully to those.

By dedicating each paragraph to only one part of your argument, you will give the reader time to fully evaluate and understand each claim before going on to the next one. Think of paragraphs as a way of guiding your reader’s attention—by giving them a single topic, you force them to focus on it. When you direct your readers’ focus, they will have a much easier time following your argument.

Creating Topic Sentences

Every paragraph of your argument should begin with a topic sentence that tells the reader what the paragraph will address—that is, the paragraph’s claim. By providing the reader with expectations at the start of the paragraph, you help him or her understand where you are going and how the paragraph fits in with the overall structure of your argument. Topic sentences should always connect back to and support your thesis statement.

Mistakes to Avoid in Your Topic Sentence

Creating topic sentences sounds simple, right? They are, but there are still pitfalls to avoid as you craft these important sentences.

Referring to the Paper or Paragraph Itself

You do not have to make announcements like, “This paragraph is about …” There is no need to remind your reader that he or she is reading a paper. The focus should be on the argument. This kind of announcement is unnecessary, and seeing it in a paper can be somewhat startling to the reader, who’s expecting a professional presentation.

Offering Evidence or an Example

Stick with your claim in your topic sentence, and let the rest of the paragraph address the evidence and offer examples. Keep it clear by stating the topic and the main idea. Instead of stating the following: “On one occasion, another EMT and I were held at gunpoint.” Consider a more precise example: “Twenty-first century emergency-services personnel face an ever-increasing number of security challenges compared to those working fifty to a hundred years ago.”

Being Vague

The topic may relate to your thesis statement, but you’ll need to be more specific here. Consider a sentence like this: “Cooking is difficult.” The claim is confusing because it is not clear for whom cooking is difficult and why. A better example would be, “While there are food pantries in place in some low-income areas, many recipients of these goods have neither the time nor the resources to make nutritionally sound meals from what they receive.” (Stylistically speaking, if you wanted to include “Cooking is difficult,” you could make it the first sentence, followed by the topic sentence. The topic sentence should be precise.)

In expository writing, each paragraph should articulate a single main idea that relates directly to the thesis statement. This construction creates a feeling of unity, making the paper feel cohesive and purposeful. Connections between each idea—both between sentences and between paragraphs—should enhance that sense of cohesion.

Why Use Transitions?

Following the parts of a poorly constructed argument can feel like climbing a rickety ladder. Transition words and phrases add the girders and railings, smoothing the journey of reading your paper, so it feels more like climbing a wide, comfortable staircase.

Using transitions will make your writing easier to understand by providing connections between paragraphs or between sentences within a paragraph. A transition can be a word, phrase, or sentence—in longer works, they can even be a whole paragraph. The goal of a transition is to clarify for your readers exactly how your ideas are connected.

Transitions refer to both the preceding and ensuing sentence, paragraph, or section of a written work. They remind your readers of what they just read, and tell them what will come next. By doing so, transitions help your writing feel like a unified whole.

Transitions Between Paragraphs

The textbook Write Here, Right Now argues that transitions help the reader understand how one paragraph relates to the previous one. Transitions between paragraphs and ideas are vital both the organization of your writing and your ability to keep the reader engaged.

Topic Sentences

Example

Thus, whether it is being used to foster cooperation or perpetuate conflict, language has always been a commons accessible to all members who wish to contribute meaningfully to their community.

Justice defines language as “A method of communication that is available to virtually all humans to use;” a “common property, available to everyone free.” Justice thereby establishes language as a common human right and desire—an inherent need that is obvious even in the simple naming and describing of a “proto-language” like “Me Tarzan, you Jane…”

The bolded sentence above is the topic sentence of Paragraph 3—it is what we want this paragraph to do. The final sentence of the previous paragraph and the opening sentence of the current paragraph work well to demonstrate that language, whether it is used to argue or agree, is a “commons” desired by and available to everyone. Such a connected argument solidifies our claim that Justice is establishing language as the tool that facilitates arguments but produces understanding and community through these arguments.

Concluding Sentences

A paragraph’s concluding sentence also offers an excellent opportunity to begin the transition to the next paragraph—to wrap up one idea and hint at the next.

You can use a question to signal a shift:

“It’s clear, then, that the band’s biggest-selling original compositions were written early in their career, but what do we know about their later works?”

Alternatively, you could conclude by comparing the idea in the current paragraph with the idea in the next:

“While the Democratic Republic of Congo is rich in natural resources, it has led a troubled political existence.”

An “if-then” structure is a common transition technique in concluding sentences:

“If we are decided that climate change is now unavoidable, then steps must be taken to avert complete disaster.”

Here, you’re relying on the point you’ve just proven in this paragraph to serve as a springboard for the next paragraph’s main idea.

Transitions Within Paragraphs

Transitions within a paragraph help readers to anticipate what is coming before they read it. Within paragraphs, transitions tend to be single words or short phrases. Words like while, however, nevertheless, but, and similarly, as well as phrases like on the other hand and for example, can serve as transitions between sentences and ideas.

Signal Phrases

Another transitional option within a paragraph is the use of signal phrases, which alert the reader that he or she is about to read referenced material, such as a quotation, a summation of a study, or statistics verifying a claim. Ideally, your signal phrases will connect the idea of the paragraph to the information from the outside source.

-

“In support of this idea, Jennifer Aaker of the Global Business School at Stanford University writes that …”

-

“In fact, the United Nations Environmental Program found that …”

-

“However, ‘Recycling programs,’ the Northern California Recycling Association retorts …”

-

“As graph 3.2 illustrates, we can by no means be certain of the outcome.”

Such phrases prepare the reader to receive information from an authoritative source and subconsciously signal the reader to process what follows as evidence in support of the point being made. Table 9.1, “Common Signal-Phrase Verbs” displays common action words you can use to introduce quotes and evidence.

| Signal-Phrase Verbs | Signal-Phrase Verbs | Signal-Phrase Verbs | Signal-Phrase Verbs |

|---|---|---|---|

| acknowledges | confirms | implies | rejects |

| adds | contends | insists | reports |

| admits | declares | notes | responds |

| argues | denies | observes | suggests |

| asserts | disputes | points out | things |

| believes | emphasizes | reasons | writes |

| claims | grants | refutes |

Appropriate Use of Transition Words and Phrases

Before using a particular transitional word or phrase, be sure you completely understand its meaning and usage. For example, if you use a word or phrase that indicates addition (“moreover,” “in addition,” “further”), you must actually be introducing a new idea or piece of evidence. A common mistake with transitions is using such a word without actually adding an idea to the discussion. That confuses readers and puts them back on rickety footing, wondering if they missed something.

Whenever possible, stick with transition words that actually have meaning and purpose. Overusing transition words, or using them as filler, is distracting to the reader. “It is further concluded that,” for example, sounds unnatural and a little grandiose because of the passive voice. “Also,” or “Furthermore” would be clearer choices, less likely to make the reader’s eyes roll.

With that said, here are some examples of transitional devices that might be useful once you’ve verified their appropriateness:

| Result | Transitional Devices | Sample Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| To indicate addition | and, again, and then, besides, equally important, finally, further, furthermore, nor, too, next, lastly, what’s more, moreover, in addition, still, first (second, etc.) | “Strength of idea is indeed a factor in entrepreneurial success, but equally important is economic viability.” |

| To indicate comparison | whereas, but, yet, on the other hand, however, nevertheless, on the contrary, by comparison, where, compared to, up against, balanced against, although, conversely, in contrast, although this may be true, likewise, while, whilst, although, even though, on the one hand, on the other hand, in contrast, in comparison with, but, yet, alternatively, the former, the latter, respectively, all the same | “In contrast to what we now consider his pedantic prose, his poetry seemed set free to express what lies in every human heart.” |

| To indicate a logical connection | because, for, since, for the same reason, obviously, evidently, furthermore, moreover, besides, indeed, in fact, in addition, in any case, that is | “The Buddha sat under the bodhi tree for the same reason Jesus meditated in the desert: to vanquish temptation once and for all.” |

| To show exception | yet, still, however, nevertheless, in spite of, despite, of course, once in a while, sometimes | “Advocates of corporate tax incentives cite increased jobs in rural areas as an offset; still, is that sufficient justification for removing their financial responsibilities?” |

| To show time | immediately, thereafter, soon, after a while, finally, then, later, previously, formerly, first (second, etc.), next, and then | “First, the family suffered a devastating house fire that left them without any possessions, and soon thereafter learned that their passage to the New World had been revoked due to a clerical error.” |

| To summarize or indicate repetition | in brief, as I have said, as I have noted, as has been noted, as we have seen, to summarize | “We have seen, then, that not only are rising temperatures and increased weather anomalies correlated with an increase in food and water shortages, but animal-migration patterns, too, appear to be affected.” |

| To indicate emphasis | definitely, extremely, obviously, in fact, indeed, in any case, absolutely, positively, naturally, surprisingly, notwithstanding, only, still, it cannot be denied | “Obviously, such a highly skilled architect would not usually be inclined to give his services away, and yet this man volunteered his services over and again to projects that paid him only through appreciation.” |

| To indicate sequence | first, second, third, and so forth, next, then, following this, at this time, now, at this point, after, afterward, subsequently, finally, consequently, previously, before this, simultaneously, concurrently | “So, finally, the author offers one last hint about the story’s true subject: the wistful description of the mountains in the distance.” |

| To indicate an example | for example, for instance, in this case, in another case, on this occasion, in this situation, take the case of, to demonstrate, to illustrate, consider. | “Take, for example, the famous huckster P. T. Barnum, whose reputation as ‘The Prince of Humbugs’ belied his love and support of the finer things of life, like opera.” |

| To qualify a statement | under no circumstances, mainly, generally, predominantly, usually, the majority, most of, almost all, a number of, some, a few, a little, fairly, very, quite, rather, almost | “Generally, we can assume that this statement has merit, but in this specific case, it behooves us to dig deeper.” |

Adapted from “Chapter 7” of Writing, 2015, used under Creative Commons CC-BY-SA 4.0

Two Formulas for Paragraph Structure

We have looked at the basic parts of your essay, and now we have a sample formula to help you expand your ideas about your evidence. Between the Introduction (and thesis) and the Conclusion (and reflection on the thesis) comes the body of the essay. For your essay’s body to be solid and focused, it needs to have clear, well-developed paragraphs. Even paragraphs need to have a beginning, middle, and end. To help you think about paragraph organization, think about TEAR:

T = Topic Sentence

This is like a little thesis for your paragraph. It tells the reader what that paragraph is all about. If your reader were only to read the topic sentences in your essay, he/or she should have a general idea of what you’re talking about. Of course, he/she can’t get a complete picture unless you provide…

E = Evidence

This is the “how do you know?” part of your paragraph. Evidence comes from the real world. You may present your evidence in the form of statistics, direct quotes, summaries, or paraphrases from a source, or your own observations. Evidence is available to us all. What your reader needs is for you to make sense of that evidence so that s/he understands what all this has to do with your thesis or claim. That is why you provide…

A = Analysis

This is the ‘so what?’ part of your paragraph. You say what is important and why. This isn’t just personal taste or opinion. You have to provide good reasons to support your conclusions. And just to make sure you’re still on track, you…

R = Reflection

This sentence concludes the paragraph and relates to the topic sentence and the thesis. Ideally, it should also prepare us for the next paragraph.

Note

Transitions are like the mortar between the bricks. Transitions hold our ideas together and move us gracefully from point to point. Some common transition words or phrases may include although, therefore, because, in fact, for example, on the other hand, while, in addition, in contrast, then again, furthermore, but back to our main point…

To help you think about TEAR, imagine your snarky little brother looking over your shoulder as you compose, asking you:

T = “What’s all this about?”

E = “How do you know?”

A = “Why should I care?”

R = “What does this have to do with anything?”

You may be thinking, I’ve heard this before, but it wasn’t called TEAR. It was called….

PIE

What does PIE stand for?

P = Point. This is the point of the paragraph, or the topic sentence.

I = Illustration. This is where you illustrate your point with evidence

E = Explanation. This is where you explain how that evidence supports your point. This is your analysis.

Why give you two ways to think of this? Because you may find that to fully develop your paragraph, you’ll need to add a little more evidence and analysis. And it looks a little funny to write TEAEAR. So, you can think of PIE-IE-IE will always love you.

Take a look at the picture above. Notice anything? No two slices are the same. So it should be in your essay. Each paragraph should do its own job, have its own focus. Sure, your essay may feature a variety of related paragraphs grouped in sections; however, to avoid repeating information or losing focus in your essay, remember that each slice of PIE should serve a unique purpose.

Adapted from “Chapter 9” of Successful Writing, 2012, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, Write Here, Right Now: An Interactive Introduction to Academic Writing and Research Copyright © 2018 by Ryerson University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted, and a handout created by CNM English instructor Patricia O’Connor.