Chapter 34: Recognizing the Rhetorical Situation and Rhetorical Fallacies

The term argument, like rhetoric and critique, is another term that can carry negative connotations (e.g., “We argued all day,” “He picked an argument,” or “You don’t have to be so argumentative”), but like these other terms, it’s simply a neutral term. In academic writing, an argument is using rhetorical appeals to influence an audience and achieve a certain set of purposes and outcomes.

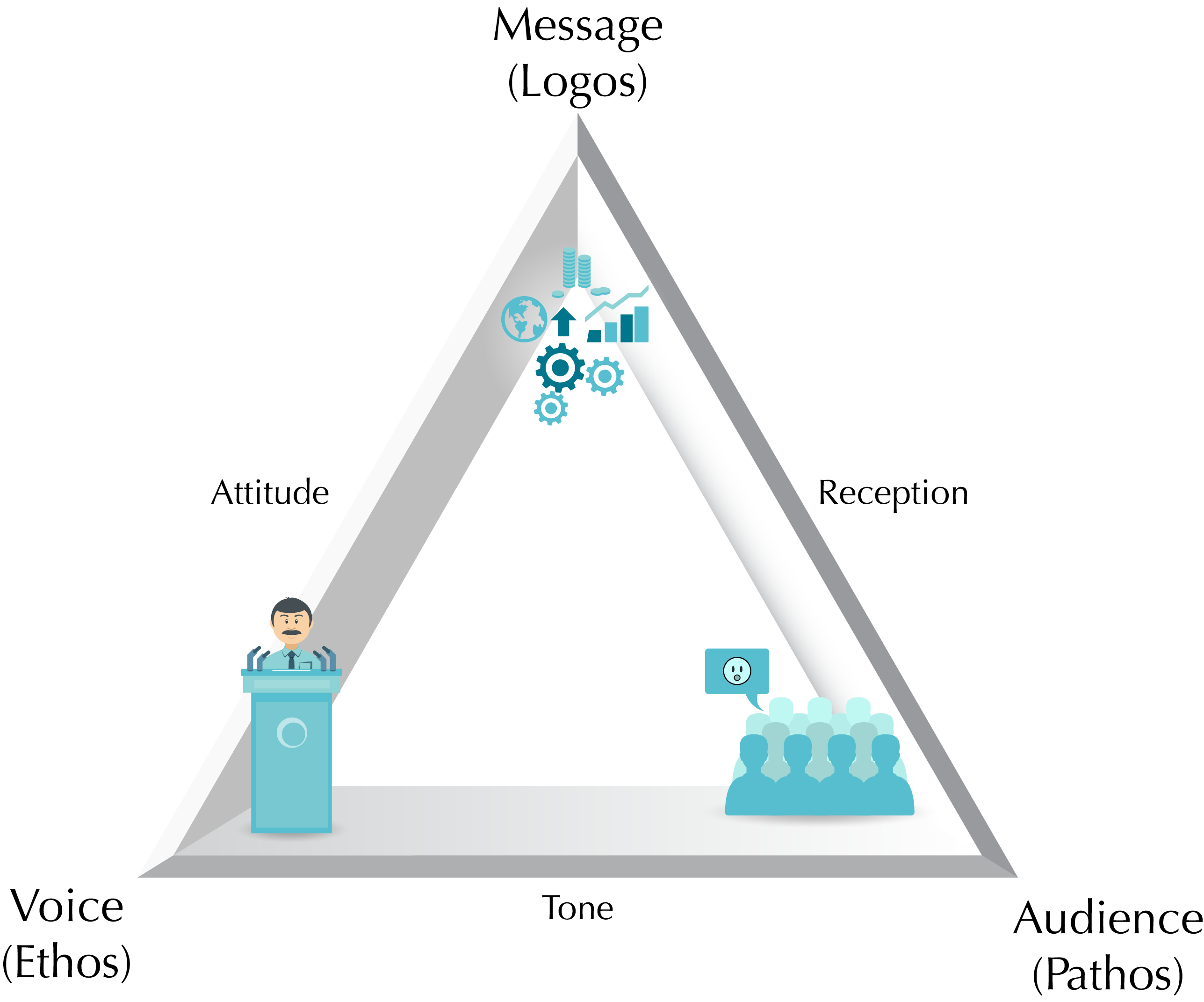

The Rhetorical Triangle

The principles Aristotle laid out in his Rhetoric nearly 2,500 years ago still form the foundation of much of our contemporary practice of argument. Teachers often use a triangle to illustrate the rhetorical situation present in any piece of communication; the triangle suggests the interdependent relationships among its three elements: the voice (the speaker or writer), the audience (the intended listeners or readers), and the message (the text being conveyed).

If each corner of the triangle is represented by one of the three elements of the rhetorical situation, then each side of the triangle depicts a particular relationship between two elements:

-

Tone. The connection established between the voice and the audience.

-

Attitude. The orientation of the voice toward the message it wants to convey.

-

Reception. The manner in which the audience receives the message conveyed.

Rhetorical Appeals

In this section, we’ll focus on how the rhetorical triangle can be used in service of argumentation, especially through the balanced use of ethical, logical, and emotional appeals: ethos, logos, and pathos, respectively.

In the preceding figure, you’ll note that each appeal has been placed next to the corner of the triangle with which it is most closely associated:

-

Ethos. Appeals to the credibility, reputation, and trustworthiness of the speaker or writer (most closely associated with the voice).

-

Pathos. Appeals to the emotions and cultural beliefs of the listeners or readers (most closely associated with the audience).

-

Logos. Appeals to reason, logic, and facts in the argument (most closely associated with the message).

Each of these appeals relies on a certain type of evidence: ethical, emotional, or logical. Based on your audience and purpose, you have to decide what combination of techniques will work best as you present your case.

When using a logical appeal, make sure to use sound inductive and deductive reasoning to speak to the reader’s common sense. Specifically, avoid using emotional comments or pictures if you think your audience will see their use as manipulative or inflammatory. For example, in an essay proposing that participating in high school athletics helps students develop into more successful students, you could show graphs comparing the grades of athletes and non-athletes, as well as high school graduation rates and post–high school education enrollment. These statistics would support your points in a logical way and would probably work well with a school board that is considering cutting a sports program.

The goal of an emotional appeal is to garner sympathy, develop anger, instill pride, inspire happiness, encourage a call to action, or trigger other emotions. When you choose this method, your goal is for your audience to react emotionally regardless of what they might think logically. In some situations, invoking an emotional appeal is a reasonable choice. For example, if you were trying to convince your audience that a certain drug is dangerous to take, you might choose to show a harrowing image of a person who has had a bad reaction to the drug. In this case, the image draws an emotional appeal and helps convince the audience that the drug is dangerous. Unfortunately, emotional appeals are also often used unethically to sway opinions without solid reasoning.

An ethical appeal relies on the credibility of the author. For example, a college professor who places a college logo on a website gains some immediate credibility from being associated with the college. An advertisement for tennis shoes using a well-known athlete gains some credibility. You might create an ethical appeal in an essay on solving a campus problem by noting that you are serving in student government. Ethical appeals can add an important component to your argument, but keep in mind that ethical appeals are only as strong as the credibility of the association being made.

Whether your argument relies primarily on logos, pathos, ethos, or a combination of these appeals, plan to make your case with your entire arsenal of facts, statistics, examples, anecdotes, illustrations, figurative language, quotations, expert opinions, discountable opposing views, and common ground with the audience. Carefully choosing these supporting details will control the tone of your paper as well as the success of your argument.

Logical, Emotional, and Ethical Fallacies

Rhetorical appeals have power. They can be used to motivate or to manipulate. When they are used irresponsibly, they lead to fallacies.

Bonus Video

Five Fallacies | Idea Channel | PBS Digital Studios

If you would like to dig deeper into logical fallacies, the fallacy playlist of common fallacies provided by the PBS Idea Channel.

Rhetorical fallacies are, at best, unintentional reasoning errors, and at worst, they are deliberate attempts to deceive. Fallacies are commonly used in advertising and politics, but they are not acceptable in academic arguments. The following are some examples of three kinds of fallacies that abuse the power of logical, emotional, or ethical appeals (logos, pathos, or ethos).

| Logical Fallacies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Begging the question (or circular reasoning): The point is simply restated in different words as proof to support the point. | Tall people are more successful because they accomplish more. |

| Either/or fallacy: A situation is presented as an “either/or” choice when in reality, there are more than just two options. | Either I start to college this fall, or I work in a factory for the rest of my life. |

| False analogy: A comparison is made between two things that are not enough alike to support the comparison. | This summer camp job is like a rat cage. They feed us and let us out on a schedule. |

| Hasty generalization: A conclusion is reached with insufficient evidence. | I wouldn’t go to that college if I were you because it is extremely unorganized. I had to apply twice because they lost my first application. |

| Non sequitur: Two unrelated ideas are erroneously shown to have a cause-and-effect relationship. | If you like dogs, you would like a pet lion. |

| Post hoc ergo propter hoc (or false cause and effect): The writer argues that A caused B because B happened after A. | George W. Bush was elected after Bill Clinton, so it is clear that dissatisfaction with Clinton led to Bush’s election. |

| Red herring: The writer inserts an irrelevant detail into an argument to divert the reader’s attention from the main issue. | My room might be a mess, but I got an A in math. |

| Self-contradiction: One part of the writer’s argument directly contradicts the overall argument. | Man has evolved to the point that we clearly understand that there is no such thing as evolution. |

| Straw man: The writer rebuts a competing claim by offering an exaggerated or oversimplified version of it. | Claim—You should take a long walk every day. Rebuttal—You want me to sell my car, or what? |

| Emotional Fallacies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Apple polishing: Flattery of the audience is disguised as a reason for accepting a claim. | You should wear a fedora. You have the perfect bone structure for it. |

| Flattery: The writer suggests that readers with certain positive traits would naturally agree with the writer’s point. | You are a calm and collected person, so you can probably understand what I am saying. |

| Group think (or group appeal): The reader is encouraged to decide about an issue based on identification with a popular, high-status group. | The varsity football players all bought some of our fundraising candy. Do you want to buy some? |

| Riding the bandwagon: The writer suggests that since “everyone” is doing something, the reader should do it too. | The hot trend today is to wear black socks with tennis shoes. You’ll look really out of it if you wear those white socks. |

| Scare tactics (or veiled threats): The writer uses frightening ideas to scare readers into agreeing or believing something. | If the garbage collection rates are not increased, your garbage will likely start piling up. |

| Stereotyping: The writer uses a sweeping, general statement about a group of people in order to prove a point. | Women won’t like this movie because it has too much action and violence. OR Men won’t like this movie because it’s about feelings and relationships. |

| Ethical Fallacies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Argument from outrage: Extreme outrage that springs from an overbearing reliance on the writer’s own subjective perspective is used to shock readers into agreeing instead of thinking for themselves. | I was absolutely beside myself to think that anyone could be stupid enough to believe that the Ellis Corporation would live up to its commitments. The totally unethical management there failed to require the metal grade they agreed to. This horrendous mess we now have is completely their fault, and they must be held accountable. |

| False authority (or hero worship or appeal to authority or appeal to celebrity): A celebrity is quoted or hired to support a product or idea to sway others’ opinions. | LeBron James wears Nikes, and you should too. |

| Guilt by association: An adversary’s credibility is attacked because the person has friends or relatives who possibly lack in credibility. | We do not want people like her teaching our kids. Her father is in prison for murder. |

| Personal attack (or ad hominem): An adversary’s personal attributes are used to discredit his or her argument. | I don’t care if the government hired her as an expert. If she doesn’t know enough not to wear jeans to court, I don’t trust her judgment about anything. |

| Poisoning the well: Negative information is shared about an adversary so others will later discredit his or her opinions. | I heard that he was charged with aggravated assault last year, and his rich parents got him off. |

| Scapegoating: A certain group or person is unfairly blamed for all sorts of problems. | Jake is such a terrible student government president; it is no wonder that it is raining today and our spring dance will be ruined. |

Do your best to avoid using these examples of fallacious reasoning, and be alert to their use by others so that you aren’t “tricked” into a line of unsound reasoning. Developing the habit and skill of reading academic, commercial, and political rhetoric carefully will enable you to see through manipulative, fallacious uses of verbal, written, and visual language. Being on guard for these fallacies will make you a more proficient college student, a smarter consumer, and a more careful voter, citizen, and member of your community.

Adapted from “Chapter 4” of Writers’ Handbook, 2012, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0 US