Chapter 33: Synthesis for Research Writing

At its most basic level, a synthesis involves combining two or more summaries, but synthesis writing is more difficult than it might at first appear because this combining must be done in a meaningful way, and the final essay must generally be thesis-driven. In composition courses, “synthesis” commonly refers to writing about printed texts, drawing together particular themes or traits that you observe in those texts, organizing the material from each text according to those themes or traits, and developing your own thesis or theory. Sometimes, you may be asked to synthesize your own ideas with those of the texts you have been assigned. In your other college classes, you’ll probably find yourself synthesizing information from graphs and tables, pieces of music, and artworks as well.

Synthesis in Everyday Life

Whenever you report to a friend about a film or podcast, you engage in synthesis. People synthesize information naturally to help other see the connections between things they learn; for example, you have probably stored up a mental data bank of the various descriptions you’ve heard about particular professors. If your data bank contains several positive descriptions, you might synthesize that information and use it to enroll in a class from that professor. Synthesis is related to but not the same as classification, division, or comparison and contrast. Instead of attending to categories or finding similarities and differences, synthesizing sources is a matter of pulling them together into some kind of harmony. Synthesis searches for links between materials for the purpose of constructing a thesis or theory.

Synthesis Writing Outside of College

The basic research report (described below as a background synthesis) is a common document in the business world. Whether one is proposing to open a new store or expand a product line, the report will synthesize information and arrange it by topic rather than by source. Whether you want to present information on child rearing to a new mother, or details about your town to a new resident, you’ll find yourself synthesizing too. And just as in college, the quality and usefulness of your synthesis will depend on your accuracy and organization.

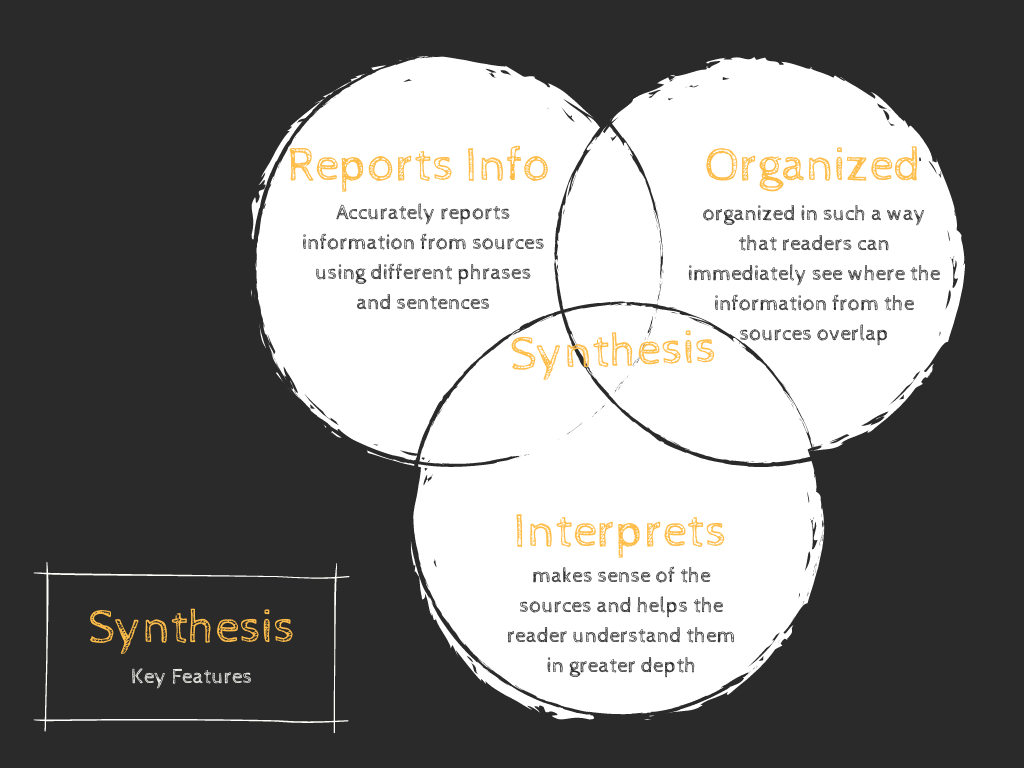

Key Features of a Research Report

(1) Accurately reports information from the sources using different phrases and sentences;

(2) Organized in such a way that readers can immediately see where the information from the sources overlap;.

(3) Makes sense of the sources and helps the reader understand them in greater depth.

Thesis Driven vs Background Synthesis for Research Writing

A synthesis can serve different purposes, depending on the assignment. In a background synthesis, your goal is to collect and organize information from various sources by topic or theme, presenting an overview of what is known about a subject. This type does not require an argument or thesis—it simply helps readers understand the current state of research or information.

In contrast, a thesis-driven synthesis not only combines information from multiple sources, but also uses that information to support a central claim or argument. Here, you evaluate and interpret the sources to develop your own perspective or theory about the topic.

Both types require you to organize information meaningfully, but a background synthesis remains neutral, while a thesis-driven synthesis aims to persuade or prove a point.

A Synthesis of the Literature

As a college student, you may be asked to begin research papers with a synthesis of the sources. Your primary purpose is to show readers that you are familiar with the field and are qualified to offer your own opinions. But your larger purpose is to show that in spite of all this wonderful research, no one has addressed the problem in the way that you intend to in your paper. This gives your synthesis a purpose and even a thesis of sorts. Because each discipline has specific rules and expectations, you should consult your professor or a guidebook for that specific discipline if you are asked to write a review of the literature and aren’t sure how to do it.

Preparing to Write Synthesis

When preparing to write a synthesis, begin by briefly summarizing the shared points or themes. Identify patterns or traits that will help you organize your essay by topic or theme. Sometimes your assignment will suggest these; other times you must choose them yourself. Making a comparison and creating outlines can help clarify your purpose before you begin writing.

Writing The Synthesis Essay

A synthesis essay should be organized so that others can understand the sources and evaluate your comprehension of them and their presentation of specific data, themes, etc. The following format works well.

The introduction of a synthesis essay:

I. The introduction (usually one paragraph)

1. Contains a one-sentence statement that sums up the focus of your synthesis.

2. Also introduces the texts to be synthesized:

(i) Gives the title of each source (following the citation guidelines of whatever style

sheet you are using);

(ii) Provides the name of each author;

(ii) Sometimes also provides pertinent background information about the authors,

about the texts to be summarized, or about the general topic from which the

texts are drawn.

The body of a synthesis essay:

I. The introduction (usually one paragraph)

1. Introduces the texts to be synthesized:

(i) Gives the title of each source (following the citation guidelines of whatever style

sheet you are using);

(ii) Provides the name of each author;

(ii) Sometimes also provides pertinent background information about the authors,

about the texts to be summarized or about the general topic from which the

texts are drawn.

This should be organized by theme, point, similarity, or aspect of the topic. Your organization will be determined by the assignment or by the patterns you see in the material you are synthesizing. The organization is the most important part of a synthesis, so try out more than one format.

Individual Paragraphs

1. Begin with a sentence or phrase that informs readers of the topic of the paragraph;

2. Include information from more than one source;

3. Clearly indicate which material comes from which source using lead-in phrases and in-text citations.

[Beware of plagiarism: Accidental plagiarism most often occurs when students are synthesizing sources and do not indicate where the synthesis ends and their own comments begin or vice versa.]

4. Show the similarities or differences between the different sources in ways that make

the paper as informative as possible;

5. Represent the texts fairly–even if that seems to weaken the paper! Look upon

yourself as a synthesizing machine; you are simply repeating what the source says

in fewer words and in your own words. But the fact that you are using your own

words does not mean that you are in anyway changing what the source says.

Conclusion

When you have finished your paper, write a conclusion reminding readers of the most significant themes you have found and the ways they connect to the overall topic. You may also want to suggest further research or comment on concepts you do not discuss in the paper. If you are writing a background synthesis, it may be appropriate for you to offer an interpretation of the material or take a position (thesis). Check this option with your instructor before you write the final draft of your paper.

After learning about synthesis, use your new knowledge by reading each example and determining which category each sentence fits into: Reports Information, Organized Information, or Interpreted Information. Select the category based on whether the information summarizes source material, groups information by theme, or explains connections and insights.

Checking your own writing or that of your peers

Read a peer’s synthesis and then answer the questions below. The information provided will help the writer check that his or her paper does what he or she intended (for example, it is not necessarily wrong for a synthesis to include any of the writer’s opinions; indeed, in a thesis-driven paper this is essential; however, the reader must be able to identify which opinions originated with the writer of the paper and which came from the sources).

- What do you like best about your peer’s synthesis? (Why? How might he or she do more of it?)

- Is it clear what is being synthesized? (i.e.: Did your peer list the source(s), and cite it/them correctly?)

- Is the thesis of each original text clear in the synthesis? (Highlight your peer’s thesis.)

- If you have read the same sources, did you identify the same theses as your peer? (If not, how do they differ?)

- Did your peer include any of his own opinions in his or her synthesis? (If so, what are they?)

- Were there any points in the synthesis where you were lost because a transition was missing or material seems to have been omitted? (If so, where and how might it be fixed?)

- What is the organizational structure of the synthesis essay? (It might help to draw a plan/diagram.)

- Does this structure work? (If not, how might your peer revise it?)

- How is each paragraph structured? (It might help to draw a plan/diagram.)

- Is this method effective? (If not, how should your peer revise?)

- Was there a mechanical, grammatical, or spelling error that annoyed you as you read the paper? (If so, how could the author fix it? Did you notice this error occurring more than once?) Do not comment on every typographical or other error you see. It is a waste of time to carefully edit a paper before it is revised.

- What other advice do you have for the author of this paper?

Adapted from “Synthesis Writing,” written By Sandra Jamieson, published by Drew University, and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 1.0 License