Chapter 3: Reading Strategies

Now that you know what adjustments students should consider as they prepare for college writing, we will discuss what students should consider about college reading. Obviously, reading and writing work together. Therefore, while reading, consider your writing situation. Your college courses, not just this one, will sharpen both your reading and your writing skills. Most of your writing assignments—from brief response papers to in-depth research projects—will depend on your understanding of course reading assignments or related readings you do on your own. And it is difficult, if not impossible, to write effectively about a text that you do not understand. Even when you do understand the reading, it can be hard to write about it if you do not feel personally engaged with the ideas discussed.

Developing Strong Reading Strategies

This section discusses strategies you can use to get the most out of your college reading assignments. These strategies fall into three broad categories:

- Planning strategies.To help you manage your reading assignments before you begin reading.

- Active Reading strategies.To help you understand the material while you read.

- Application strategies. To solidify your understanding at a higher and deeper level after you finish reading.

1. Planning Strategies: Pre-reading, Time Management, and Setting a Purpose

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam? Or found yourself skimming a detailed email from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? If so, you’ve likely experienced both situations as less than ideal. That’s because research shows that cramming and procrastinating have to do with emotional dysregulation that can be helped with good time management skills. Therefore, the first step in handling college reading successfully is planning. This involves pre-reading, managing your time, and setting a clear purpose for your reading.

Pre-reading is a smart strategy that means exactly what it sounds like. It’s something you do before you actually start reading. The time you spend on pre-reading, five to ten minutes, actually saves you time in the long run. Think of it as an investment – the more time you put in up front, the more you can learn and remember from your reading! Here is a short list of pre-reading tips:

- Ask yourself, What do I already know about this topic? Hint: Look at the title to learn the topic. Asking yourself what you already know about a topic activates your prior knowledge about it. Doing this helps your brain wake up its dendrites where that prior knowledge is stored so that it knows where the new knowledge will connect.

- Flip through the pages, reading the captions found under any pictures, tables, and other graphics.

- Pay attention to italicized or bolded Are these words defined for you in the margin or in a glossary?

- Read the comprehension questions you find in the margins or at the end of the chapter.

- Count how many sections of the chapter there are.

Managing your time – Now that you know how many sections make up the entire reading assignment, focus on setting aside enough time for reading and breaking the assignment into manageable chunks. For example, if you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, it is best not to wait until the night before to get started. How you choose to break up the reading assignment will depend on the type of reading it is. If the text is dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, you may need to read no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you will be able to handle more pages in one sitting. And if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

The third planning strategy is setting a purpose for your reading. Knowing what you want to achieve from a reading assignment not only helps you determine how to approach that task, but it also helps you stay focused during those moments when you are up late, already tired, or unmotivated because relaxing in front of the television sounds far more appealing than curling up with a stack of journal articles. Sometimes your purpose is simple. You might just need to understand the reading material well enough to discuss it intelligently in class the next day. However, your purpose will often go beyond that. For instance, you might also need to read in order to compare two texts, to formulate a personal response to a text, or to gather ideas for future research. Here are some questions to ask yourself to help determine your purpose:

- How did my instructor frame the assignment? Often your instructors will tell you what they expect you to get out of the reading:

- Read Chapter 2 and come to class prepared to discuss current teaching practices in elementary math.

- Read these two articles and compare Smith’s and Jones’s perspectives on the 2010 healthcare reform bill.

- Read Chapter 5 and think about how you could apply these guidelines to running your own business.

- How deeply do I need to understand the reading? If you are majoring in computer science and you are assigned to read Chapter 1, “Introduction to Computer Science,” it is safe to assume the chapter presents fundamental concepts that you will be expected to master. However, for some reading assignments, you may be expected to form a general understanding but not necessarily master the content. Again, pay attention to how your instructor presents the assignment.

- How does this assignment relate to other course readings or

to concepts discussed in class? Your instructor may make some of these connections explicitly, but if not, try to draw connections on your own. (Needless to say, it helps to take detailed notes both when in class and when you read.) - How might I use this text again in the future? If you are assigned to read about a topic that has always interested you, your reading assignment might help you develop ideas for a future research paper. Some reading assignments provide valuable tips or summaries worth bookmarking for future reference.

2. Active Reading Strategies: What to Do During Reading

Now that you have planned your approach to accomplishing the reading assignment and invested 5-10 minutes in pre-reading, how will you make sure you actually understand (comprehend) all the information? Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer or more complex, so you will need a plan for how to handle them.

When reading to learn, also called study reading, it is never enough to sit back with your reading material, move your eyes across page after page until you’ve reached the end of your assignment, and expect to remember what you just read, let alone actually learn what you needed to or were expected to from the reading. Therefore, you need to be an active reader. Maybe you’ve already developed your own system to remain active while you read. If you have, and it works for you, stick with it! But if you haven’t, here are several research-supported tips for you to try: *These tips can be applied to both physical texts and digital texts. With physical texts, read with a highlighter and a pen or pencil in hand. For digital texts, use a browser extension (like Scrible) that allows you to highlight and annotate your online text.

- Read when you’re awake, not when you’re about to take a nap or go to sleep for the night.

- Read with light snacks and water to drink nearby. No one can stay focused on an empty stomach!

- Highlight key terms, unknown words (Never skip over a word if you don’t know its meaning. Look it up and jot a brief, understandable definition above your highlight.), and main points. Most readers tend to highlight too much, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines, making it difficult to pick out the main points when it is time to review. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read.

- Annotate (write notes in the margins) – in the form of questions, comments, personal connections, and answers to the questions you read during pre-reading. Writing down your thoughts while you are reading serves as a visual aid for studying and makes it easier for you to remember what you’ve read. This is a brain-friendly practice because the human brain can only hold information for about 20 seconds in its working memory before the next idea comes and boots the previous thought off its workbench, so be sure to write down anything you want to remember before it evaporates into thin air!

- Develop a system of symbols. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

- Engage with digital text by highlighting, annotating, and tabbing areas you want to return to.

Watch the following video on annotating texts:

The following interactive image provides examples of different annotation tools that you can mimic when you are reading text for any of your college courses. Please engage with this image to learn more about annotation options.

3. Application Strategies: Reflect and Encode After Reading

Don’t allow the time you just invested in actively reading go to waste! Take a few additional minutes, just as you did for pre-reading, to reflect and to encode the information. Using these strategies is brain-friendly, and they will help you remember what you’ve read so that you can retrieve the information when you need it again for a class discussion, a test, or an application in your daily life.

Reflect – You should go through what you read and try to answer the questions you noted before during the pre-reading stage. Check in after every section, chapter or topic to make sure you understand the material and can explain it, in your own words. Pretend you are responsible for teaching this section to someone else. Can you do it? It’s at this stage that you consolidate knowledge, so refrain from moving on until you can recall the core information.

Here is a list of ideas to reflect on after you’ve completed a reading assignment:

- What is the CONTEXT in which this text was written? (This writing contributes to what topic, discussion, or controversy? Context is bigger than this one written text.)

- Who is the intended AUDIENCE? (There’s often more than one intended audience.)

- What is the author’s PURPOSE? To entertain? To explain? To persuade? (There’s usually more than one purpose, and essays almost always have an element of persuasion.)

- How is this writing ORGANIZED? Compare and contrast? Classification? Chronological? Cause and effect? (There’s often more than one organizational form.)

- What is the author’s TONE? (What are the emotions behind the words? Are there places where the tone changes or shifts?)

- What TOOLS does the author use to accomplish her/his purpose? Facts and figures? Direct quotations? Fallacies in logic? Personal experience? Repetition? Sarcasm? Humor? Brevity?

- What is the author’s THESIS—the main argument or idea, condensed into one or two sentences?

Encode – Last, look back at all of your highlights and annotations and create a separate, organized study tool. Some students like to use the Cornell Notes format for this. The benefits of doing this step are enormous. Research shows that not only do students encode the material at a deeper level than students who do not do this step, but while you organize your annotations, your brain is reviewing the information, so you will spend less time studying later.

Watch the following video on writing Cornell Notes from annotations:

Identifying Main Points

Regardless of what type of expository text , any non-fiction text that aims to educate the reader, you are assigned to read, your primary comprehension goal is to identify the main point: the most important idea that the writer wants to communicate and often states early on. Finding the main point gives you a framework to organize the details presented in the reading and relate the reading to concepts you learned in class or through other reading assignments. After identifying the main point, you will find the supporting points, the details, facts, and explanations that develop and clarify the main point.

In college, you will read a wide variety of materials, including the following:

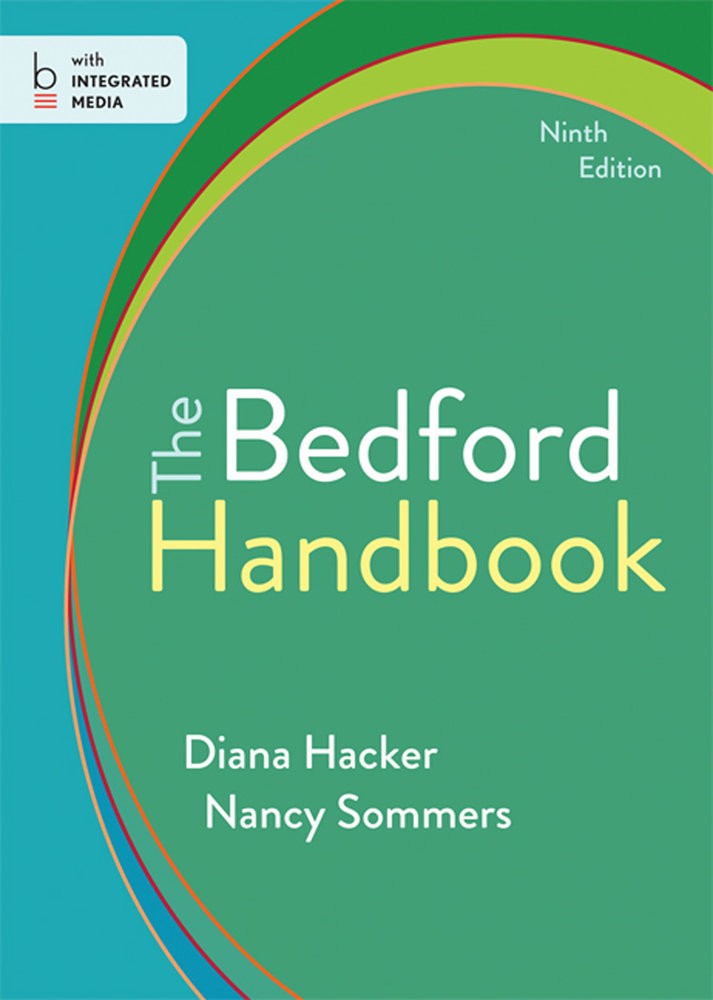

- Textbooks. These usually include summaries, glossaries, comprehension questions, and other study aids.

- Nonfiction trade books. These address a large audience and are less likely to include the study features found in textbooks. Examples include fiction, non-fiction, memoir, history, science, and more.

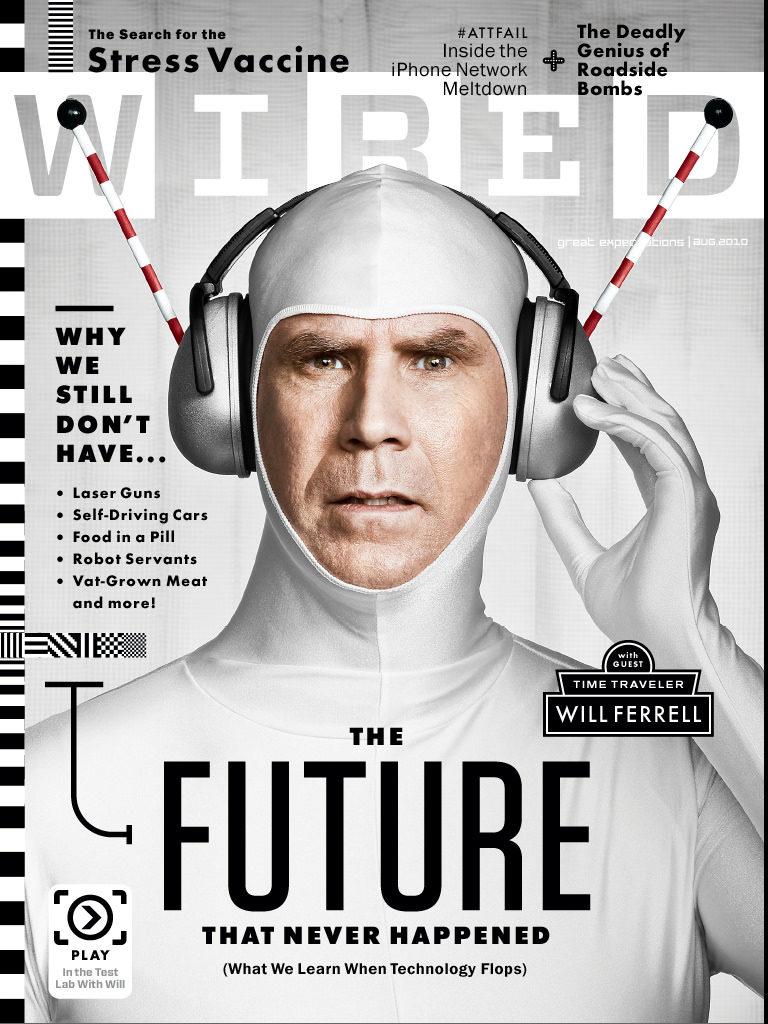

- Popular magazine, newspaper, or web articles. These are usually written for a general audience.

Some texts make the task of identifying main points relatively easy. Textbooks, for instance, include the aforementioned features as well as headings and subheadings intended to make it easier for students to identify core concepts. Graphic features, such as sidebars, diagrams, and charts, help students understand complex information and distinguish between essential and inessential points. When you are assigned to read from a textbook, be sure to use available comprehension aids to help you identify the main points.

Trade books and popular articles may not be written specifically for an educational purpose; nevertheless, they also include features that can help you identify the main ideas. These features include the following:

- Trade books. Many trade books include an introduction that presents the writer’s main ideas and purpose for writing. Reading chapter titles (and any subtitles within the chapter) will help you obtain a broad sense of what is covered. It also helps to read the beginning and ending paragraphs of a chapter closely. These paragraphs often sum up the main ideas presented.

- Popular articles. Reading the headings and introductory paragraphs carefully is crucial. In magazine articles, these features (along

with the closing paragraphs) present the main concepts. Hard news articles in newspapers present the gist of the news story in the lead paragraph, while subsequent paragraphs present increasingly general details.

At the far end of the reading difficulty scale are scholarly books and journal articles. Because these texts are written for a specialized, highly educated audience, the authors presume their readers are already familiar with the topic. The language and writing style is sophisticated and sometimes dense. To learn more about researching using these genres, check out Gathering Reliable Information.

When you read scholarly books and journal articles, try to apply the same strategies discussed in this chapter. An introduction in a scholarly article will usually present the writer’s thesis, the idea, or the hypothesis the writer is trying to prove. Headings and subheadings can help you understand how the writer has organized support for his or her thesis. Additionally, academic journal articles often include a summary at the beginning, called an abstract, and electronic databases include summaries of articles, too.

Please complete the following activity to test your knowledge:

CC Licensed Content, Original

Reading Strategies, written by Jessica Mills, 2020, published by Central New Mexico Community College, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

“Chapter One ” of Successful Writing, 2012, used according to Creative Commons 3.0 by-NC-sa

and Chapter 12: Active Reading Strategies, written by Heather Syrett, provided by Austin Community College and licensed in the Public Domain: No Known Copyright