Chapter 13: Proofreading and Peer Review

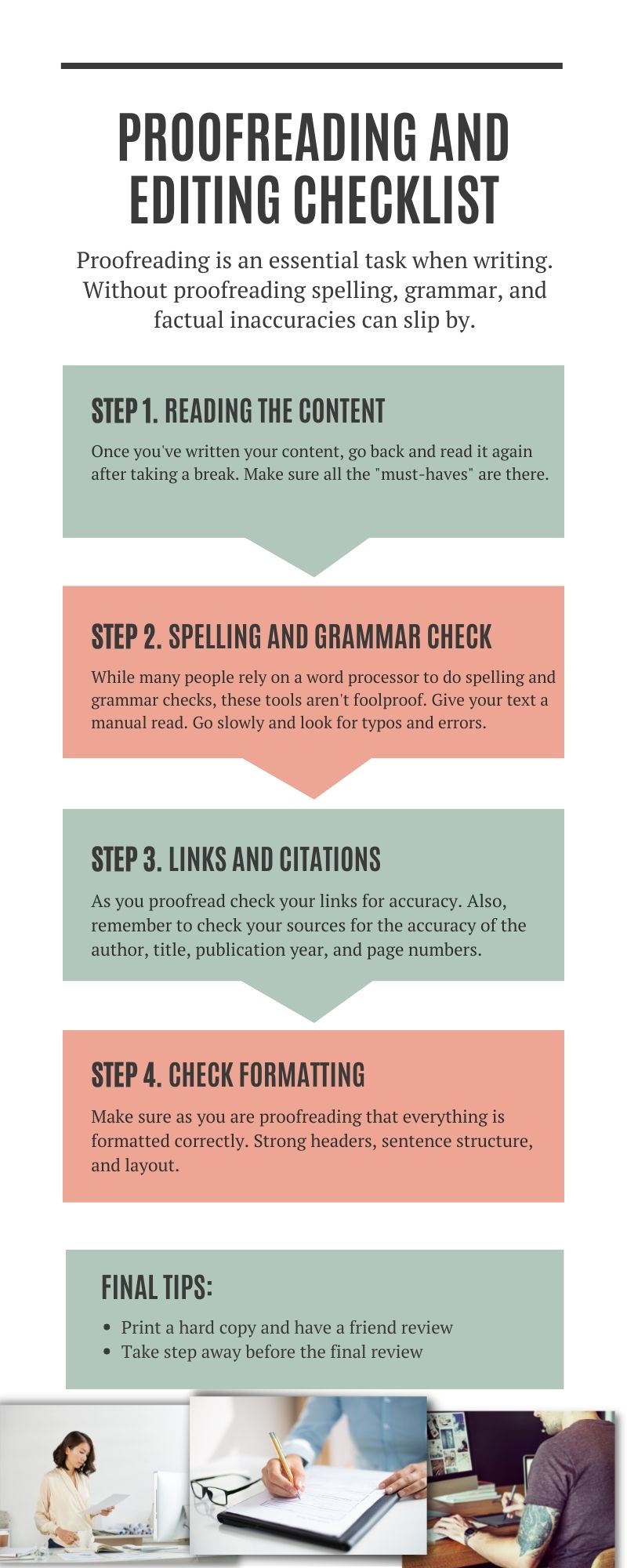

In addition to revising, you will also want to go back to your paper one more time to proofread, which will prepare you for the peer review process. The Writers’ Handbook suggests that after you have made some revisions to your draft based on feedback and your recalibration of your purpose for writing, you may now feel your essay is nearly complete. However, you should plan to read through the entire final draft at least one additional time. During this stage of editing and proofreading your entire essay, you should be looking for general consistency and clarity. Also, pay particular attention to parts of the paper you have moved around or changed in other ways to make sure that your new versions still work smoothly.

Although you might think editing and proofreading aren’t necessary since you were fairly careful when you were writing, the truth is that even the brightest people and best writers make mistakes when they write. One of the main reasons that you are likely to make mistakes is that your mind and fingers are not always moving along at the same speed nor are they necessarily in sync. So what ends up on the page isn’t always exactly what you intended. A second reason is that, as you make changes and adjustments, you might not totally match up the original parts and revised parts. Finally, a third key reason for proofreading is because you likely have errors you typically make and proofreading gives you a chance to correct those errors.

Editing and proofreading can work well with a partner. You can offer to be another pair of eyes for peers in exchange for them doing the same for you. Whether you are editing and proofreading your work or the work of a peer, the process is basically the same. Although the rest of this section assumes you are editing and proofreading your work, you can simply shift the personal issues, such as “Am I…” to a viewpoint that will work with a peer, such as “Is she…”

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for advice from a more objective reader. The textbook English for Business Success explains that what writers need most is feedback from readers who can respond to both the words on the page and critique whether the writing responds to the assignment; this process is called peer review. The in-class (and sometimes online) peer review process provides writers with the opportunity to share their drafts with someone who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses. Since your peers have participated in the same lectures, discussions, and group work, they can offer the most constructive and focused feedback based on the assignment and the instructor’s expectations.

Peer review can feel scary because you may feel uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, but remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Peer feedback activities have an educational purpose which is putting the writer into the position of the reader and with this switch, reflecting on and improving one’s own writing. You and your peers have all the tools to offer advice since you have been working together, in the classroom, to understand the essay’s topic and genre. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The sample peer review below provides a useful framework for the peer review process.

Giving Feedback

When giving feedback, try to answer your instructor’s questions, but of course, you should carefully read your classmates’ writing first. For example, if you are supposed to identify the main idea of your classmate’s writing, be sure to look for the main idea. If you can’t find it, say, “I looked but couldn’t find it”, instead of “You didn’t include one.” Both may mean the same thing, but the former sounds less aggressive and accusatory, and the reason for that is that you state that you as the reader tried to accomplish the given task of finding the thesis statement.

Good peer reviews should begin with something that the writer did well, but they should be honest in stating what needs improvement.

According to Alice Macpherson and Christina Page (Learning to Learn), good feedback should include the following:

- What the writer did well

- What needs improvement

- What the next steps are

Receiving Peer Feedback

When receiving peer feedback, remember that your classmates are being asked to perform a task and that they, just like you, are just trying to perform the task the teacher asked them to perform. With repeated practice you and your classmates will get better and better at giving each other peer review. Some of your classmates will give you great feedback and others might not have actually read your paper so their feedback might not be useful to you.

Avoid the “Ugly Baby Syndrome” that some writing teachers talk about. Someone who gives you constructive criticism on your writing may come across as someone who is calling your baby ugly. Perhaps your baby just needs a haircut. Or maybe your baby needs a diaper change. Your baby is still your creation, and you have opportunities to make your ideas shine. Fortunately, you can improve your writing, which takes us to the next point. Should you change your writing?

If two or several of your classmates make the same comment about your writing, the likely answer to that question is yes. If your teacher or a tutor has in the past commented on the same point, again the answer is yes. If the feedback is specific to the questions that your instructor asked, the answer is also yes.

If, however, your classmate’s feedback is off the topic and commenting on points not included in the peer review questions, I suggest you take a step back and return to your paper with an objective view to see if you indeed need to take action on your classmate’s feedback. And if your peer gives you feedback on grammar, and you are not certain the feedback is correct, ask for a second opinion.

Lastly, thanking your classmates for feedback is a gracious way to acknowledge that your classmates attempted to complete the assignment and took the time and care to read and comment on your writing.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

Ultimately the changes you make to your essay are up to you since it is not necessary to incorporate every recommendation you receive. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might receive feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it. These differing opinions most commonly occur when students ask people outside the classroom to review their writing. While the advice from different readers can be great, you should always value the feedback you receive from your classmates because they have participated in the class discussions, are familiar with your instructor’s expectations, and have often completed the same reading assignments as you.

When you receive differing feedback you should evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback as you work to finalize your paper.

The following matching activity will provide you with revision advice you can implement into your own writing process. Click on the cards and match the images. Each match will reveal advice provided by CNM writing instructors. Good luck!

How to Offer Your Peer Advice

Students often worry about the peer review process, especially if they have never been asked to peer review before. The best way to address this fear is to accept that you will be unable to locate every error or weakness. Once you understand that the process is not perfect, it is easier to feel comfortable with your role as the reviewer. Here are a few tips that will help you during the peer review process:

- Begin by reading the assignment instructions. Your instructor will likely have clear goals for the peer review process, and following the instructions will help you provide significant and meaningful revision ideas for your peer.

- Read your peer’s essay from the beginning to the end without adding any comments. This first read allows you to grasp your peer’s intentions and focus.

- Complete a second reading of your peer’s draft and start looking for strengths and weaknesses. Make comments on the margins of your peer’s essay. Later, you can further expand on these comments when you complete the peer review form.

- Stop when you feel stuck and ask yourself, “If this were my paper, how would I revise it?”

- Set aside time to review the organization of your peer’s essay. Read their thesis statement and make sure their body paragraphs have topic sentences that connect to their thesis statement. If there isn’t a clear connection, consider helping your peer revise their topic sentence so the connection between the thesis and body paragraph is easy to understand.

- Be honest. Your peers want to earn the best grade they can, and your advice during peer review will help them achieve this goal. Think of every piece of advice as constructive criticism. Your advice will help them to create a stronger, more focused writing sample.

The peer review process has the potential to help you create a much stronger and more focused essay. Try to be open to the process and give honest and thoughtful critiques.

Adapted from “Chapter Eight” of Writers’ Handbook, 2012, used according to Creative Commons 3.0 CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 , and “Chapter Seven” of English for Business Success, 2012, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 Student Guidelines for Effective Feedback from Write the World