Chapter 1: Introduction to College Writing at CNM

This textbook was designed for English 1110 and 1120, Composition I and Composition II, respectively. If you are enrolled in one of these courses, you may be nearing the end of your studies at Central New Mexico Community College (CNM), you may be just starting your studies at CNM, or you may have already taken this class but didn’t finish. The reality is every English 1110 and 1120 course at CNM contains a diverse range of students. If you are enrolled in English 1110 or 1120 at CNM, you are likely a resident of New Mexico (NM). You might have gone to an elementary or secondary school here. You might feel like a part of the unique culture here in NM. Wherever you started, we welcome you to CNM!

The graphic below lists the outcomes for English 1110 and 1120, which will be introduced by your instructor and included in your syllabus.

Course Outcomes: Composition I & II

Composition I: English 1110

- Analyze communication through reading and writing skills.

- Employ writing processes such as planning, organizing, composing, and revising.

- Express a primary purpose and organize supporting points logically.

- Use and document research evidence appropriate for college-level writing.

- Employ academic writing styles appropriate for different genres and audiences.

- Identify and correct grammatical and mechanical errors in their writing.

Composition II: English 1120

- Analyze the rhetorical situation for purpose, main ideas, support, audience, and organizational strategies in a variety of genres.

- Employ writing processes such as planning, organizing, composing, and revising.

- Use a variety of research methods to gather appropriate, credible information.

- Evaluate sources, claims, and evidence for their relevance, credibility, and purpose.

- Quote, paraphrase, and summarize sources ethically, citing and documenting them appropriately.

- Integrate information from sources to effectively support claims and for other purposes ( to provide background information, evidence/examples, illustrate an alternative view, etc.).

- Use an appropriate voice ( including syntax and word choice).

Did You Know

Being a CNM student means that you are enrolled at the largest post-secondary institution in the state.

CNM offers resources that can help you not only with your studies but also with managing your responsibilities as well. In this textbook, we’ll cover the conventions of writing, and we’ll also cover some of the resources available to you as a CNM student. And since this book is free and available on the internet, you can keep it…forever!

This textbook is an Open Educational Resource (OER) text, which means it was created using free and available sources on the Internet, namely eight different open access books. Our compiled textbook will shift between free, outside writing resources and the plural first pronoun voice, or the we voice, signaling the English teachers who compiled and developed sections of the text.

Throughout this text, the writers–all CNM English faculty, some of whom are still paying back student loans–are the we who compiled this textbook. We did so because we believe that a college education should be engaging, enlightening, informative, life-affirming, worldview-upturning and affordable. We believe it shouldn’t cost money to learn how to write, and that is why we are making this book available to you. This project also would not have happened without the support of CNM’s OER initiative and Liberal Arts administration.

This textbook will cover ways to communicate effectively as you develop insight into your own style, writing process, grammatical choices, and rhetorical situations. With these skills, you should be able to improve your writing talent regardless of the discipline you enter after completing this course. Knowing your rhetorical situation, or the circumstances under which you communicate, and knowing which tone, style, and genre will most effectively persuade your audience, will help you regardless of whether you are enrolling in history, biology, theater, or music next semester–because when you get to college, you write in every discipline. To help launch our introduction this chapter includes a section from the open access textbook Successful Writing.

As you begin this chapter, you may wonder why you need an introduction. After all, you have been writing and reading since elementary school. You completed numerous assessments of your reading and writing skills in high school and as part of your application process for college. You may write on the job, too. Why is a college writing course even necessary?

It can be difficult to feel excited about an intro writing course when you are eager to begin the coursework in your major (and if you are an English major, let your teacher know so you can talk about your future education plans). Regardless of your field of study, honing your writing skills—plus your reading and critical-thinking skills—will help you build a solid academic foundation.

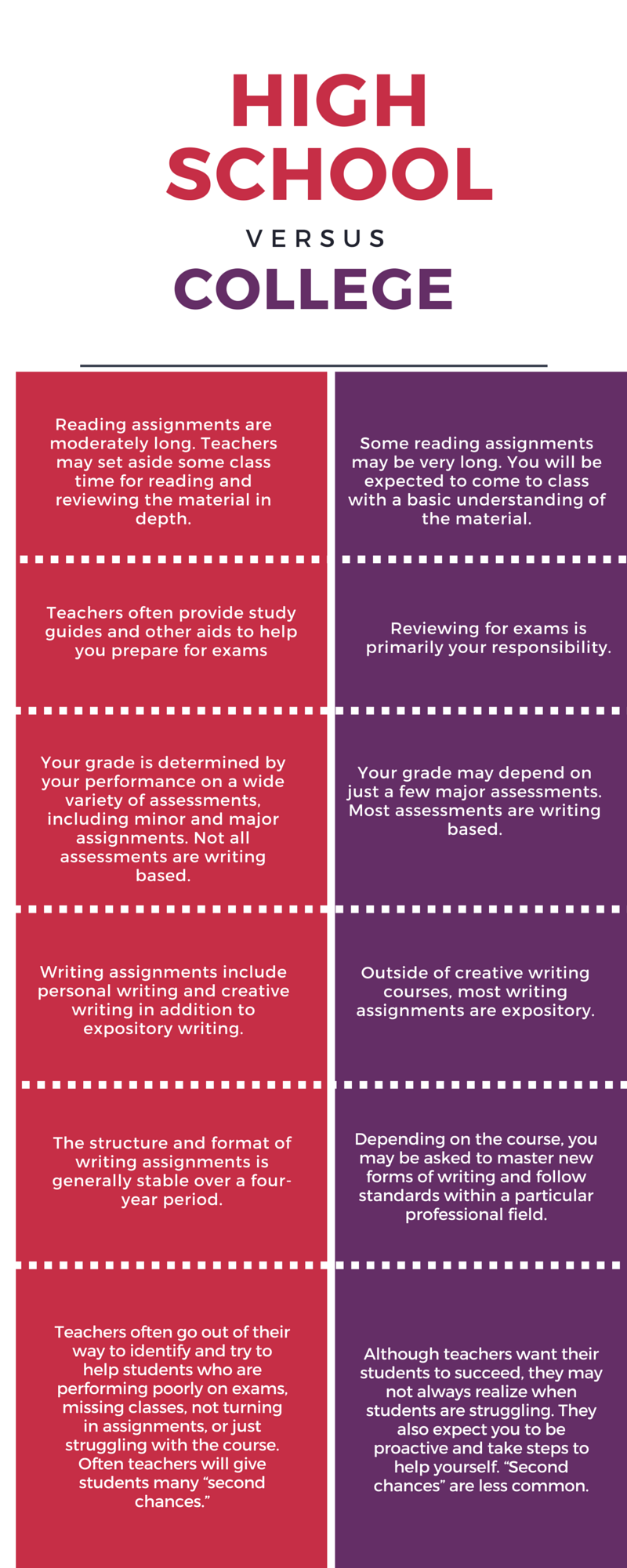

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work you are expected to complete increases. When instructors expect you to read pages upon pages or study hours and hours for one particular course, managing your workload can be challenging. This chapter includes strategies for studying efficiently and managing your time.

The quality of the work you do also changes. It is not enough to understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will also be expected to seriously engage with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about a given subject. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. A good introductory writing course will help you swim.

Seeking Help Meeting College Expectations

Depending on your education before coming to CNM, you will have varied writing experiences as compared with other students in class. Some students might have earned a GED, some might be returning to school after a decades-long break, and still other students might either be graduating high school, or be freshly graduated. If the latter is the case, you might enter college with a wealth of experience writing five-paragraph essays, book reports, and lab reports. Even the best students, however, need to make big adjustments to learn the conventions of academic writing. College-level writing obeys different rules, and learning them will help you hone your writing skills. Think of it as ascending another step up the writing ladder.

Many students feel intimidated asking for help with academic writing; after all, it’s something you’ve been doing your entire life in school. However, there’s no need to feel like it’s a sign of your lack of ability; on the contrary, many of the strongest student writers regularly seek help and support with their writing (that’s why they’re so strong). College instructors are familiar with the ups and downs of writing, and most colleges have support systems in place to help students learn how to write for an academic audience. The following sections discuss common on-campus writing services, what to expect from them, and how they can help you.

Tutoring Center

CNM students have access to The Learning and Computer Center (TLCc), which is available on six campuses: Advanced Technology Center, Main, Montoya, Rio Rancho, South Valley, and Westside. At these writing centers, trained tutors help students meet college-level expectations. The tutoring centers offer one-on-one meetings, online, and group sessions for multiple disciplines. TLCc also offers workshops on citing and learning how to develop a writing process.

Student-Led Workshops

Some courses encourage students to share their research and writing with each other, and even offer workshops where students can present their own writing and offer constructive comments to their classmates. Independent paper-writing workshops provide a space for peers with varying interests, work styles, and areas of expertise to brainstorm.

Writing in drafts makes academic work more manageable. Drafting gets your ideas onto paper, which gives you more to work with than the perfectionist’s daunting blank screen. You can always return later to fix the problems that bother you.

Communicating in a College Course

Communication courses teach students that communication involves two parties—the sender and the receiver of the communicated message. Sometimes, there is more than one sender and often, there is more than one receiver of the message. The main purpose of communication whether it be email, text, tweet, blog, discussion, presentation, written assignment, or speech is always to help the receiver(s) of the message understand the idea that the sender of the message is trying to share. This section will focus on electronic communication in a college course.

Email or message

An email or message sent to your instructor is often the result of a question you may have. Many students think contacting their instructor shows that they weren’t paying attention or that they are the only student did not understand something, so they often keep quiet and go on trying to do work that they do not understand. Other students think that their teacher is their own private tutor, so they email or message the teacher several times a day to ask questions that likely have answers in the syllabus and in the learning module instructions. Both of these behaviors are unhelpful and frustrating to the students and the instructor.

On the other hand, avoid monopolizing your teacher’s email inbox with dozens of emails and messages per week and expecting her to respond immediately. Nobody enjoys having their inbox blown up with multiple messages by the same person. Try to remember your instructor will likely have many other emails from administrators, staff, and other students.

Avoid sending harsh or demanding emails or messages when you are panicked, frustrated, or angry. Walk away from your computer and return at a later time when you feel calmer. Then re-read the instructions, or syllabus, or the course materials you find confusing, and if you still cannot find the answer because it is not there, definitely email or message your instructor.

Tips for Emailing Your Instructor

- Be polite: Address your professor formally, using the title “Professor” or “Instructor” with their last name. Depending on how formal your professor seems, use a salutation (“Dear” or “Hello” followed by your professor’s name/title (Dr. XYZ, Professor XYZ, etc.)

- Pose a question. Clearly introduce the purpose of your email and the information you are requesting. If you are not asking a specific question, be aware that you may not receive a response to your email.

- Be concise. Instructors are busy people, and although they are typically more than happy to help you, kindly get to your point quickly. Sign off with your first and last name, the course number, and the class time. This will make it easy for your professor to identify you.

- Do not ask, “When will you return our papers?” If you MUST ask, make it specific and realistic (e.g., “Will we get our papers back by the end of next week?”). Most Instructors teach multiple classes and could have hundreds of assignments to grade.

- Do not ask your Instructor if you missed anything important when you were absent. Instructors work diligently to design their coursework, so asking if any of that content was important can be considered rude or dismissive of their hard work. Instead ask if missed anything that was not included on the course schedule.

Creating an appropriate tone can feel overwhelming. We know that all emails should be polite, and emails to your instructor may be more formal or professional. Not all Instructors will expect formal emails, but it’s important to remember that your instructor is not your friend and that an email or message is not a text message. It is not appropriate to send an informal or colloquial message and to assume your instructor is your friend or acquaintance and that an email or message is the same as text message.

Sample Email to an Instructor

Subject: English 1110 Section 102: Absence

Dear/Hello Professor [Last name],

l was unable to attend class today, so I wanted to ask if there are any handouts or additional assignments I should complete before we meet on Thursday? I did review the syllabus and course outline, and I will complete the quiz and reading homework listed there.

Many thanks,

[First name] [Last name]

Communication on Public Discussion Boards

Whenever you are being asked to communicate or post in a discussion forum or other communication mode, you need to ask yourself if there will be one recipient or several. In other words, who will be your readers? Is the forum private so that only your instructor or only a group of classmates or only a specific classmate can see it or is it public so that everyone, all of your classmates and your instructor can see your post? Check the forum to which you are posting for these settings.

The discussion board is a public forum, so you might have a broad audience. Create a post according to the recipient(s). It is nice to address a classmate by name if you are responding to a specific person in a discussion forum. Online classes can be a solitary experience, so it can be nice when a classmate is actually responding to you, personally. It is also advisable to use a greeting such as “Classmates” if you are addressing a discussion post to everyone in the class. Most of the time, discussions tend to be public, so you can make sure of the assignment’s settings before you post.

Do’s: Discussions usually have specific guidelines for posts. Most require you to use college English and write in complete sentences. This chapter from CNM’s grammar OER covers appropriate language. Essentially, you should avoid text language, capitalize “I”, and check your spelling, grammar, and punctuation before submitting your posts. Sometimes there are specific questions and a certain number of sentences required, so read the instructions closely. Avoid short posts, such as “I agree” because it is too general and doesn’t encourage ongoing discussion; instead, explain what you agree with and why. Often, there is a reading that needs to be completed before you post. Make sure you read the required text before posting instead of just “winging it” because your classmates and teacher can tell.

Don’ts: Avoid copying and pasting your own post to respond to several of your classmates. Your instructor, who will be viewing and grading your posts, can tell that your posts are identical and is unlikely to give you full credit for identical posts. Second, avoid copying and pasting your classmates’ posts to present as your own. There is a timestamp on your posts in an online classroom, and your instructor will have physical evidence of who posted a response first. Also, your classmates and instructor will notice your copied post, and you will be guilty of plagiarism. Last, do not post unrelated ideas; for example, if you are asked about the main idea of a text you read, make sure to read the text, and respond by giving what you think is the main idea, not by posting that you liked the text because of a personal experience you had. It isn’t wrong to include personal content, but be sure to answer the instructor’s questions first to earn full credit.

Communicating in a college classroom with multiple audiences can be complex, but these tips will help you create respectful and thoughtful messages.

Complete this knowledge check before moving onto another chapter.

This chapter is a synthesis of three texts:

- Adapted from “Boundless Writing”

- Adapted from “Chapter One ” of Successful Writing, 2012, used according to creative commons 3.0 cc-by-nc-sa

- Some sections of this chapter written by Angelika Schwamberger, published by Central New Mexico Community College, and licensed using Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Some sections were adapted from Learning to Learn Online by Alice Macpherson and Christina Page, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.