Chapter 32: The Analytical Essay: Expressing Your Point of View

Introducing the Essay

When revising your essay, you do not have to write it in the exact order that it will be read, as any section you work on in a given moment may appear anywhere in your final draft. In fact, many times it’s best to write the introduction last because we may not know how to introduce the essay until we’ve discovered and articulated the main perspectives. Eventually you will need to consider not only what your analysis consists of, but also the effect you want it to have. An essay that commands attention seems like a discussion between intelligent and aware people, in which ideas are not thrown out randomly but in a deliberate manner with each thought leading logically to the next.

For this reason, the opening paragraph or introduction should be the place where you invite your readers into this discussion, encouraging them to read what will follow, without introducing the main content in a rigid manner or announcing what you plan to accomplish in the following paragraphs. This is know as telling your reader rather than showing your reader. So, imagine being at a party, but this time instead of meeting someone who bores you by reciting irrelevant details of the past, and they tell you exactly what will follow in the near future:

Most likely, you will find an excuse to move to the other side of the room as quickly as possible. Similarly, when writers begin their essays with a step-by-step announcement of what will follow, the reader doesn’t feel the sense of anticipation that they would when the perspective unfolds more organically. Successful analytical essay writers do not begin by blatantly spelling out the main points that they will cover. In an essay, this could include phrases like “In this paragraph I will…” or “This essay will introduce the argument that…” Instead, you should create leads, openings that hook the reader into wanting to read further.

One way to capture the reader’s attention is to share a story or anecdote that directly relates to the main perspective. For instance, you can also capture your reader’s attention with a quote or perhaps you can startle the reader with an unexpected twist. These are just a few suggestions for grabbing the reader’s attention and many other possibilities exist (though try to avoid beginning with a dictionary definition unless you want to provide your own twist on it). Whichever way you decide to open your paper, make certain that you go on to relate your lead-in to the main perspective or thesis you have on your subject. For instance, you wouldn’t want to start an essay by telling a joke that has nothing to do with the subject of your analysis just to get an easy laugh. However, it would be fine if you were to write:

There’s an old Sufi joke that points out that “the moon is more valuable than the sun because at night we need the light more.” Of course the joke’s humor arises from the fact that without the sun, it would be night all the time, and yet it does seem to be human nature to take advantage of that which is constant in our lives, the people and things that add warmth and light on a daily basis. In applying this to the television show, Mad Men, it’s easy to see how Donald Draper, the main character, undervalues his wife Betty in order to chase after other women. Though these other women are as inconstant as the moon, disappearing and reappearing in new forms, they give him light during the dark times in his life when he needs it the most. His affairs, however, do not provide lasting satisfaction, but only a fleeting illusion of happiness, much like the advertisements he creates for a living.

Notice how this paragraph leads the reader from the hook to the main focus of the essay without spelling out or announcing what will follow in a rigid manner. The Sufi joke is not simply thrown out for a chuckle, but to set up the thesis that the main character of the show prefers illusions to reality in both his personal life and his work. As a result, this paragraph is likely to engage our attention and make us want to read further.

Focusing Your Analysis

After examining your subject thoroughly and reading what others have written about it, you might have so much to write that you will not be able to cover your perspective adequately without turning your essay into a book. In such a case you have two options: briefly cover all the aspects of your subject or focus on a few key elements. If you take the first option, then your essay may seem too general or too disjointed. A good maxim to keep in mind is that it is better to say a lot about a little rather than a little about a lot; when writers try to cover too many ideas, they often end up reiterating the obvious as opposed to coming up with new insights. The second option leads to more intriguing perspectives because it focuses your gaze on the most relevant parts of your subject, allowing you to discern shades of meaning that others might have missed.

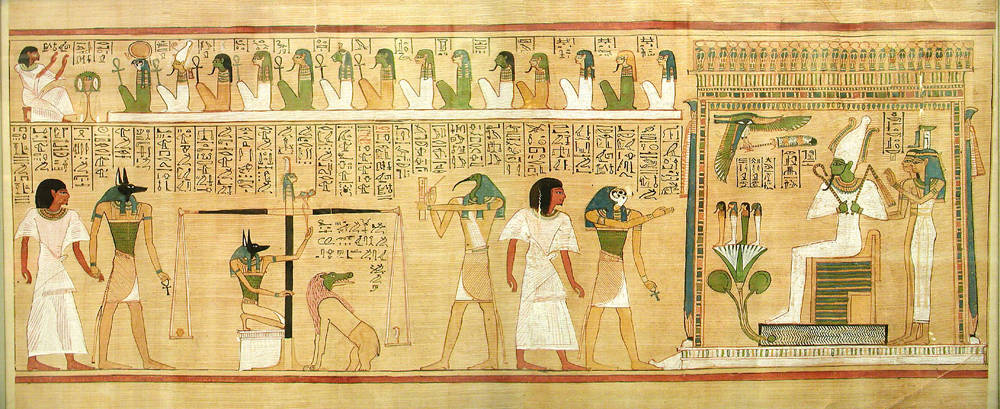

To achieve a stronger focus, you should first look again at your main perspective or working thesis to see if you can limit its scope. Consider whether you can concentrate on an important aspect of your subject. For instance, if you were writing an essay for an Anthropology class on Ancient Egyptian rituals, look over your drafts to see which particular features keep coming up. You might limit your essay to how they buried their dead, or, better, how they buried their Pharaohs, or, even better, how the legend of the God Osiris influenced the burial of the Pharaohs.

Next, see if you can delineate your perspective on the subject more clearly, clarifying your argument or the issue you wish to explore. This practice will help you move from a working thesis, such as

“Rituals played an important function in Ancient Egyptian society,”

to a strong thesis:

“Because it provided hope for an afterlife, the legend of Osiris offered both the inspiration and methodology for the burial of the Pharaohs.”

Once you have focused the scope of your thesis, revise your essay to reflect it. This practice will require you to engage in what is usually the most painful part of the writing process—cutting. If something does not fit in with your perspective, it has to go, no matter how brilliantly considered or eloquently stated. But do not throw away the parts you cut. You never know when you might find a use for them again. Just because a particular section does not fit well with the focus of one essay does not mean that you won’t be able to use it in another essay down the road. Create a second document where you can paste all the text you cut from your draft document. This allows you to go back and review the text as you continue to work on your writing.

Expanding

After cutting your essay down to the essential ideas, look it over again to make sure that you have explored each idea adequately. At this point it might help to ask yourself the following questions:

-

Do your assertions clearly reveal your perspectives on the subject?

-

Do you provide the specific examples that inspired these assertions?

-

Do you explain how you derived your assertions from a careful reading of these examples?

-

Do you explore the significance of these assertions as they relate to personal and broader concerns?

If any long sections seem lacking in any of these areas, you might explore them further by taking time out from your more formal writing to play with one of the heuristics recommended in various sections throughout this book (freewriting, brainstorming, clustering, metaphor extension, issue dialogue, and the Pentad). You can then incorporate the best ideas you discover into your essay to make each section seem more thoughtful and more thorough.

Organization of the Body Paragraphs and Transitions

Once you’ve led your readers into your essay, you can keep their attention by making certain that your ideas continue to connect with each other by writing transitions between your paragraphs and the main sections within them. At the beginning of a paragraph, a transition functions as a better kind of assertion than a topic sentence because it not only reveals what the paragraph will be about but also shows how it connects to the one that came before it. Take this paragraph you are currently reading as an example. Had I begun by simply writing a topic sentence like “A second strategy for effective writing is to develop effective transitions,” I would not only have ignored my own advice, but also would have missed an important point about how transitions, like opening paragraphs, function to lead readers through various aspects of our perspectives.

Before you can write effective transitions, you need to make certain that your paper is organized deliberately. To ensure this, you might try the oldest writing trick in the composition teacher’s handbook, the outline, discussed in more depth in Chapter 7. But wait until after you have already come up with most of your analysis.

To begin a paper with an outline requires that you know the content before you have a chance to consider it. Writing is a process of discovery—so how can you possibly put an order to ideas that you have not yet articulated? After you have written several paragraphs, you should read them again and write down the main points you conveyed in each of them on a separate piece of paper. Then consider how these points connect with each other and determine the best order for articulating them, creating a reverse outline from the content that you’ve already developed. Using this outline as a guide, you can then reorganize the paper and write transitions between the paragraphs to make certain that they connect and flow for the reader.

An excellent method for producing effective transitions is to underline the keywords in one paragraph and the keywords in the one that follows and then to write a sentence that contains all of these words. Try to show the relationship by adding linking words that reveal a causal connection (however, therefore, alternatively) as opposed to ones that simply announce a new idea (another, in addition to, also). For example, if I were to write about how I feel about having to pay taxes, the main idea of one paragraph could be:

Original assertion: Like everyone else, I hate to see so much of my paycheck disappear in taxes.

The main idea of the paragraph that follows could be: Without taxes, we wouldn’t have any public services.

My transition could be: Despite the fact that I hate to pay taxes, I understand why they are necessary because without them, we wouldn’t be able to have a police force, fire department, public schools and a host of other essential services.

If you cannot find a way to link one paragraph to the next, then you should go back to your reverse outline to consider a better place to put it. And if you cannot find any other place where it fits, then you may need to cut the paragraph from your paper (but remember to save it for potential use in a future essay).

This same advice works well for writing transitions not only between paragraphs but also within them. If you do not provide transitional clues as to how the sentences link together, the reader is just as likely to get lost:

I love my two pets. My cat, Clyde is very independent. My dog, Mac, barks if I leave him alone for too long. I can leave Clyde alone for four days. I’m only taking Clyde with me to college. I have to come home twice a day to feed Mac. Mac does a lot of tricks. Clyde loves to purr on my lap.

The reason that reading this can make us tired and confused is that we can only remember a few unrelated items in a given moment. By adding transitional phrases and words, we store the items in our memory as concepts, thus making it easier to relate the previous sentences to the ones that follow. Consider how much easier it is to read an analysis with transitions between sentences:

I have two pets that I love for different reasons. For instance, I love when my cat, Clyde, sits on my lap and purrs, and I also love when my dog Mac performs many of the tricks I’ve taught him. But when I leave for college, I plan to take only Clyde with me. Unfortunately, I can only leave Mac at home for a few hours before he starts to bark; however, Clyde is very independent and can be left in my dorm for days without needing my attention.

The previous paragraph is more like a brainstorm session, while the second is more developed. This revision not only is much easier to read and recall but also gives a sense of coherence to what previously seemed liked scattered, random thoughts.

Ending the Essay

Once you’ve led your readers all the way through to the conclusion, try not to sink their enthusiasm by beginning it with the words “in conclusion.” Not only is this phrase overused and cliché, but it also sends the wrong message. The phrase implies that you have wrapped up all the loose ends on the subject and neither you nor your readers should have any need to think about it further. Rather than close off the discussion, the last paragraph should encourage it to continue by stressing how your analysis opens up new avenues for thinking about your subject (as long as these thoughts emerge from your essay and are not completely unrelated to what you wrote about before). This is the place where you should answer the “so what” question and stress the significance of your analysis, underscoring the most important insights you discovered and the implications for further thought and action.

However you choose to stress the importance of your analysis in your final paragraph, you can do so without simply repeating what you wrote before. If you have effectively led your readers through your paper, they will remember your main points and will most likely find a final summary to be repetitive and annoying. A much stronger choice is to end with a statement or observation that captures the importance of what you have written without having to repeat each of your main points. For example, in his book, City of Quartz, Mike Davis ends his discussion of how Southern Californians do not care to preserve their past by calling attention to a junkyard full of zoo and amusement park icons:

Scattered amid the broken bumper cars and ferris wheel seats are nostalgic bits and pieces of Southern California’s famous extinct amusement parks (in the pre-Disney days when admission was free or $1); the Pike, Belmont Shores, Pacific Ocean Park, and so on. Suddenly rearing up from the back of a flatbed trailer are the fabled stone elephants and pouncing lions that once stood at the gates of Selig Zoo in Eastlake (Lincoln) Park, where they had enthralled generations of Eastlake kids. I tried to imagine how a native of Manhattan would feel, suddenly discovering the New York Public Library’s stone lions discarded in a New Jersey wrecking yard. I suppose the Selig lions might be Southern California’s summary, unsentimental judgment on the value of its lost childhood. The past generations are like so much debris to be swept away by the developers’ bulldozers.

Davis, Mike. City of Quartz. New York: Vintage Books, 1990. 435

Imagine, if, instead of this paragraph, he had written:

In conclusion, I have shown many instances in which Southern Californians try to erase their past. First, I showed how they do so by constructing new buildings, concentrating especially on the Fontana region. Second, I showed…

Can’t you just feel the air leaving your sails?

In light of this advice, you have probably already discerned that certain parts of your essay will emphasize various aspects of analysis. The beginning of the paper will announce your main assertion or thesis, and the transitions in subsequent paragraphs will present corollary assertions. The bulk of your paper will most likely center on your examples and explanations, and the end will focus more on the significance. However, try to make certain that all of these elements are present to some degree throughout your essay. A long section without any significance may cause your readers to feel bored, a section without assertions may cause them to feel confused, and a section without examples or explanations may cause them to feel skeptical.

Why Good People Turn Bad Online

Gaia Vince

Why Good People Turn Bad Online

References

The New Statesman tracked abusive tweets sent to women MPs in the run-up to the 2017 UK general election.

A 2017 Pew Research Center survey showed that 41 percent of Americans have experienced online harassment.

Researchers at University College London investigated what hunter-gatherers can tell us about social networks.

Research published in PNAS showed that emotion influences how content spreads online.

In 2016, Ars Technica reported a study showing how Twitter bots can reduce racist slurs.

Community Security Trust, a charity that protects British Jews from anti-Semitism, published a report about anti-Semitic content on Twitter in 2018.

Gaia Vince is a journalist, broadcaster, and author who specializes in science, the environment, and social issues. Her article first appeared in Mosaic.

Why Good People Turn Bad Online by Gaia Vince is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.