Introduction

To introduce cognition, let’s start with murder!

Video: An exercise in problem-solving and attentional awareness (Transport for London, 2010)

How are we so good at recognizing faces and objects, and what’s happening when we fail in this recognition? How do we selectively attend to relevant pieces of information and why do we sometimes fail to do so? How do we form some memories so easily but fail to store or access others? How do we comprehend sentences, make decisions, and solve problems? The video above highlights a few of these processes and, notably, what happens when they don’t work as expected.

These abilities and activities involve Cognition, “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses” (Oxford Languages, 2024).

This encompasses cognitive and biological processes related to sensation, perception, attention, imagery, memory, language, judgment, reasoning, problem solving, decision making, and a host of other vital processes.

Cognitive Psychology, then, is the field of psychology dedicated to examining how people think and how the above-mentioned cognitive processes interact. Though not the first to use the term, Ulric Neisser popularized the term “Cognitive Psychology” in his 1967 textbook by the same name (Neisser, 1967). He defined cognition as:

“…all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used.”

Neisser’s definition suggests that cognition encompasses various mental processes that receive, change, interpret, and make sense of the sensory input from the world around us. Notably, this means that beyond being passive receivers of sensory information, we are actually “active selectors” of information, as well as “active interpreters” who make assumptions about our perceptions based on experience.

Consider reading a book at the park:

Our eyes and ears transduce wavelengths of light and sound (respectively) into electrical impulses that spread across massively interconnected groups of neurons in the brain.

The sensory input becomes transformed into visible and audible percepts.

Further processing may allow identification and recognition of objects and sounds within the scene, allowing us to select the target of focus (book), judge the situation, plan actions, etc.

In attending to the book, our interpretation of it may depend on our familiarity with the language, level of distraction, etc.

Cognitive processing also involves preserving the details of such experiences in memory, which allows previous experiences to be stored, retrieved, and used in the present moment.

Neisser’s definition remains current, but is also somewhat limited to a particular information processing view of cognition. In the subsequent content, we will expand on this definition and view.

Assumptions

Cognitive psychology is based on two assumptions: (1) Human cognition can at least in principle be fully revealed by the scientific method, that is, individual components of mental processes can be identified and understood, and (2) Internal mental processes can be described in terms of rules or algorithms in information processing models. There has been much debate on these assumptions (Costall and Still, 1987; Dreyfus, 1979; Searle, 1990).

Approaches

Very much like physics, experiments and simulations/modelling are the major research tools in cognitive psychology. Often, the predictions of the models are directly compared to human behaviour. With the ease of access and wide use of brain imaging techniques, cognitive psychology has seen increasing influence of cognitive neuroscience over the past decade. There are currently three main approaches in cognitive psychology: experimental cognitive psychology, computational cognitive psychology, and neural cognitive psychology (more often called cognitive neuroscience).

Experimental cognitive psychology treats cognitive psychology as one of the natural sciences and applies experimental methods to investigate human cognition. Psychophysical responses, response time, and eye tracking are often measured in experimental cognitive psychology. Computational cognitive psychology develops formal mathematical and computational models of human cognition based on symbolic and subsymbolic representations, and dynamical systems. Neural cognitive psychology uses brain imaging (e.g., EEG, MEG, fMRI, PET, and Optical Imaging techniques) and neurobiological methods (e.g., study of patients with brain damage) to understand the neural basis of human cognition. The three approaches are often inter-linked and provide both independent and complementary insights in every sub-domain of cognitive psychology.

A couple notes before we dive into Cognitive Psychology:

First, Cognitive Psychology represents just one approach to studying human behavior and mental processes.

It can (and does) co-exist with views such as neuroscience, behaviorism, social psychology, etc. There are many sub-disciplines in Psychology and we tend to find them to be complementary rather than in competition.

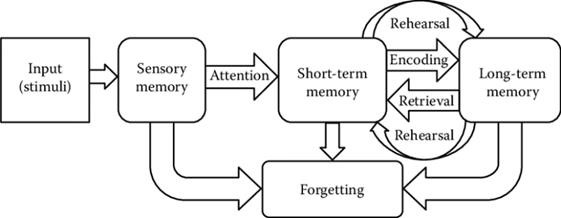

Second, a word of caution: psychologists sometimes turn abstract concepts into hypothetical “things” (constructs). For example, the boxes in the memory model below do not necessarily map onto specific/cohesive brain structures. They represent functionally separate types of processing, but the boundaries between such proposed constructs are not always clearly defined.

Be careful when making assumptions about how our cognitive processes correlate with biological events; we sometimes run the risk of concluding we can observe a process just because we have given it a name.