3.3 Visual Perception

Gestalt Psychology

In the early part of the 20th century, Max Wertheimer published a paper demonstrating that individuals perceived motion in rapidly flickering static images—an insight that came to him as he used a child’s toy tachistoscope. Wertheimer, and his assistants Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka, who later became his partners, believed that perception involved more than simply combining sensory stimuli. This belief led to a new movement in psychology called Gestalt psychology. The word gestalt literally means form or pattern, but its use reflects the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. In other words, the brain creates a perception that is more than simply the sum of available sensory inputs, and it does so in predictable ways. Gestalt psychologists translated these predictable ways into principles by which we organize and group sensory information. As a result, Gestalt psychology has been extremely influential in the area of sensation and perception (Rock & Palmer, 1990).

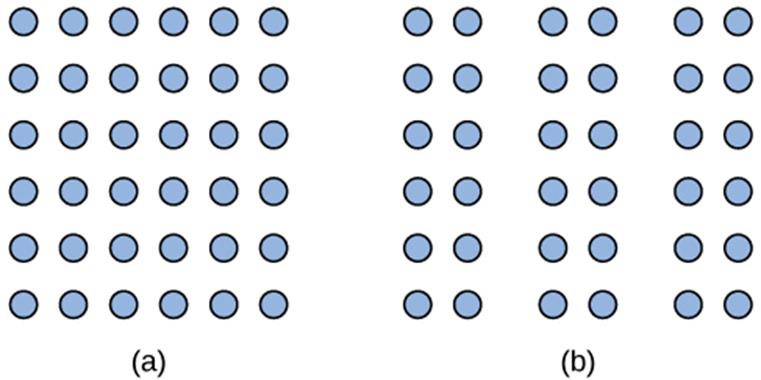

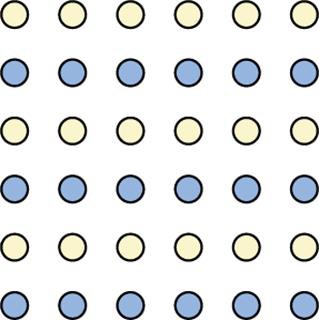

We might also use the principle of similarity to group things in our visual fields. According to this principle, things that are alike tend to be grouped together. For example, when watching a football game, we tend to group individuals based on the colors of their uniforms.

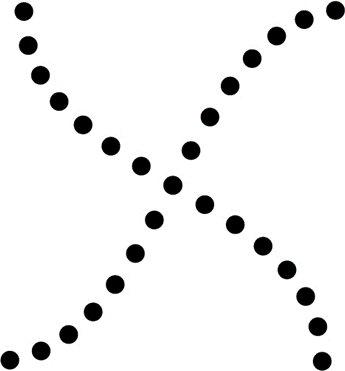

Two additional Gestalt principles are the law of continuity (or good continuation) and closure. The law of continuity suggests that we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines. The principle of closure states that we organize our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts.

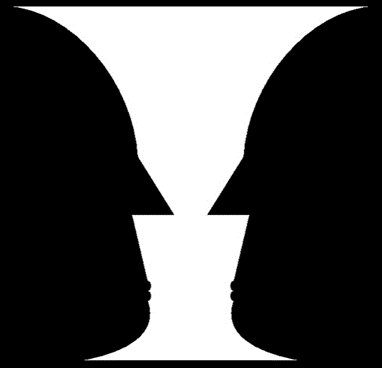

According to Gestalt theorists, pattern perception – or our ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes – occurs by following the principles grouping principles of Prägnanz (among others) described above. Prägnanz is the idea that we tend to perceive the simplest interpretation of ambiguous or complex forms.

You probably feel fairly certain that your perception accurately matches the real world, but this is not necessarily the case. Our perceptions are based on perceptual hypotheses: educated guesses that we make while interpreting sensory information. These constructed hypotheses are informed by several factors, including our personalities, experiences, and expectations.

Top-down processing in vision

As you may recall, “top-down” processing provides another context in which to discuss how our experiences and expectations can influence our interpretation of sensory events in our world. As one example, the first time you see the below image (take a look!), you may struggle to make sense of what it depicts.

However, if I tell you to find a Dalmatian in the picture, it’s hard to unsee that since your mind is “primed” with experience.

Additionally, we can receive the exact same (ambiguous) visual stimulus and interpret it differently depending on the provided context; look at the shape below. Seen alone, your brain engages in bottom-up processing. There are two thick vertical lines and three thin horizontal lines. There is no context to give it a specific meaning, so there is no top-down processing involved.

Now, look at the same shape in two different contexts. Surrounded by sequential letters, your brain expects the shape to be a letter and to complete the sequence. In that context, you perceive the lines to form the shape of the letter “B.”

Surrounded by numbers, the same shape now looks like the number “13.”

When given a context, your perception is driven by your cognitive expectations. Now you are processing the shape in a top-down fashion.

One way to think of this concept is that sensation is a physical process, whereas perception is psychological. For example, upon walking into a kitchen and smelling the scent of baking cinnamon rolls, the sensation is the scent receptors detecting the odor of cinnamon, but the perception may be “Mmm, this smells like the bread Grandma used to bake when the family gathered for holidays.”

Visual Illusions

Top-down processing can also fuel a number of perceptual illusions we encounter, highlighting such expectations. Artists and researchers alike have developed a number of interesting illusions (like these!) and a few are discussed here.

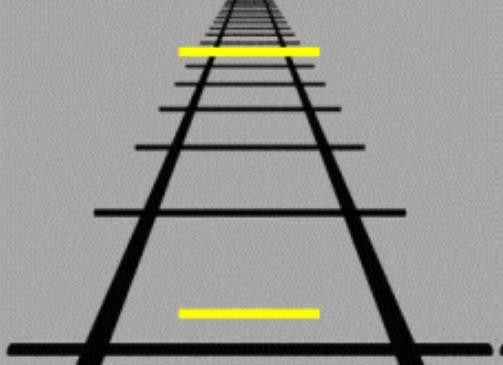

Depth Illusions: When we look at the world, we are not very good at detecting the absolute qualities of things— their exact size or color or shape. What we are particularly good at is judging objects in the context of other objects and conditions. Let’s look at a few illusions to see how they are based on insights into our perception. Look at the image below. Which of the two horizontal yellow lines looks wider, the top one or the bottom one?

Most people experience the top line as wider. They are both exactly the same length. This experience is called the Ponzo illusion. Even though you know that the lines are the same length, it is difficult to see them as identical. Our perceptual system takes the context into account, here using the converging “railroad tracks” to produce an experience of depth. Then, using some impressive mental geometry, our brain adjusts the experienced length of the top line to be consistent with the size it would have if it were that far away: if two lines are the same length on my retina, but different distances from me, the more distant line must be longer. You experience a world that “makes sense” rather than a world that reflects the actual objects in front of you. The “mental geometry” referenced above is an example of a top-down perceptual process being engaged; without the background of converging lines in the Ponzo Illusion, you would likely make fewer assumptions regarding size/distance and can typically match the line lengths more accurately.

Light and Size Illusions: Depth is not the only quality in the world that shows how we adjust what we experience to fit the surrounding world. Look at the two gray squares in the figure below. Which one looks darker?

Most people experience the square on the right as the darker of the two gray squares. You have probably already guessed that the squares are actually identical in shade, but the surrounding area—black on the left and white on the right—influence how our perceptual systems interpret the gray area. In this case, the greater difference in shading between the white surrounding area and the gray square on the right results in the experience of a darker square.

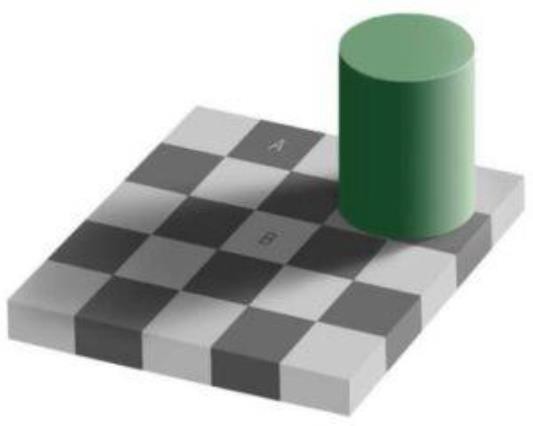

Our visual systems work with more than simple contrast. They also use our knowledge of how the world works to adjust our perceptual experience. Look at the checkerboard to the right. There are two squares with letters in them, one marked “A” and the other “B.” Which one of those two squares is darker?

This seems like an easy comparison, but the truth is that squares A and B are identical in shade. Our perceptual system adjusts our experience by taking some visual information into account. First, “A” is one of the “dark squares” and “B” is a “light square” if we take the checkerboard pattern into account. Perhaps even more impressive, our visual systems notice that “B” is in a shadow. Objects cast in shadow appear darker, so our experience is adjusted to consider the shadow’s effect. This results in perceiving square B as lighter than square A, which sits in the bright light. The utilization of such pattern recognition and shadow compensation highlights additional top-down processing mechanisms.

Literally, form or pattern (German). A perceptual configuration made up of elements such that the whole is different from the sum of its parts.

The Gestalt principle that we tend to perceive the simplest or most stable interpretation of ambiguous or complex forms.

Priming: the activation of certain thoughts or feelings that make them easier to think of and act upon.