7.4 Types of Long-Term Memory

If information makes it past short term-memory it may enter long-term memory (LTM), memory storage that can hold information for days, months, and years. The capacity of long-term memory is large, and there is no known limit to what we can remember (Wang, Liu, & Wang, 2003). Although we may forget at least some information after we learn it, other things will stay with us forever.

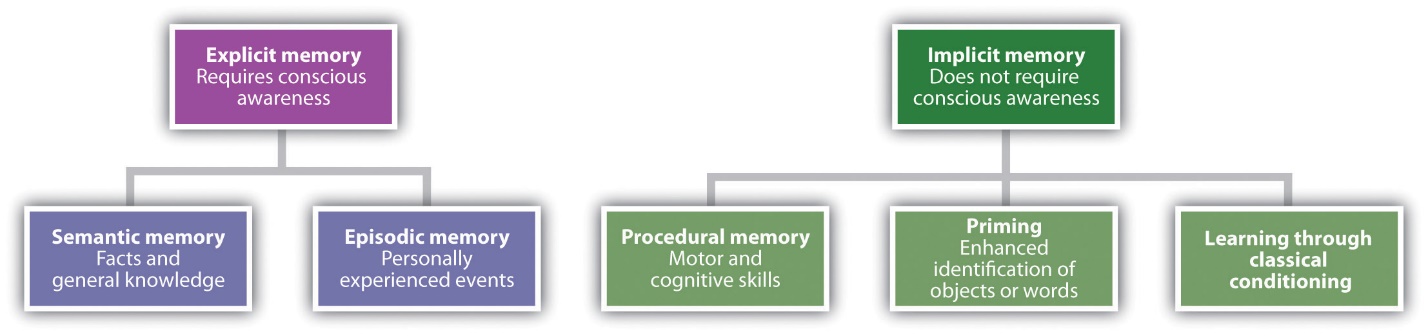

Explicit Memory

When we assess memory by asking a person to consciously remember things, we are measuring explicit memory. Explicit memory refers to knowledge or experiences that can be consciously remembered. There are two types of explicit memory: episodic and semantic. Episodic memory refers to the firsthand experiences that we have had (e.g., recollections of our high school graduation day or of the fantastic dinner we had in New York last year). Semantic memory refers to our knowledge of facts and concepts about the world (e.g., that the absolute value of −90 is greater than the absolute value of 9 and that one definition of the word “affect” is “the experience of feeling or emotion”).

Explicit memory is assessed using measures in which the individual being tested must consciously attempt to remember the information. A recall memory test is a measure of explicit memory that involves bringing from memory information that has previously been remembered. We rely on our recall memory when we take an essay test, because the test requires us to generate previously remembered information. A multiple-choice test is an example of a recognition memory test, a measure of explicit memory that involves determining whether information has been seen or learned before.

Your own experiences taking tests will probably lead you to agree with the scientific research finding that recall is more difficult than recognition. Recall, such as required on essay tests, involves two steps: first generating an answer and then determining whether it seems to be the correct one. Recognition, as on multiple-choice test, only involves determining which item from a list seems most correct (Haist, Shimamura, & Squire, 1992). Although they involve different processes, recall and recognition memory measures tend to be correlated. Students who do better on a multiple-choice exam will also, by and large, do better on an essay exam (Bridgeman & Morgan, 1996).

A third way of measuring memory is known as relearning (Nelson, 1985). Measures of relearning (or savings) assess how much more quickly information is processed or learned when it is studied again after it has already been learned but then forgotten. If you have taken some French courses in the past, for instance, you might have forgotten most of the vocabulary you learned. But if you were to work on your French again, you’d learn the vocabulary much faster the second time around. Relearning can be a more sensitive measure of memory than either recall or recognition because it allows assessing memory in terms of “how much” or “how fast” rather than simply “correct” versus “incorrect” responses. Relearning also allows us to measure memory for procedures like driving a car or playing a piano piece, as well as memory for facts and figures.

Implicit Memory

While explicit memory consists of the things that we can consciously report that we know, implicit memory refers to knowledge that we cannot consciously access. However, implicit memory is nevertheless exceedingly important to us because it has a direct effect on our behavior. Implicit memory refers to the influence of experience on behavior, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. Researchers typically distinguish between several types of implicit memory, including procedural memory, classical conditioning effects, and priming.

Procedural memory refers to our often unexplainable knowledge of how to do things. When we walk from one place to another, speak to another person in English, dial a cell phone, or play a video game, we are using procedural memory. Procedural memory allows us to perform complex tasks, even though we may not be able to explain to others how we do them. There is no way to tell someone how to ride a bicycle; a person has to learn by doing it. The idea of implicit memory helps explain how infants are able to learn. The ability to crawl, walk, and talk are procedures, and these skills are easily and efficiently developed while we are children despite the fact that as adults we have no conscious memory of having learned them.

A second type of implicit memory is classical conditioning associations, in which we learn, often without effort or awareness, to associate neutral stimuli (such as a sound or a light) with another stimulus (such as food), which creates a naturally occurring response, such as enjoyment or salivation. The memory for the association is demonstrated when the conditioned stimulus (the sound) begins to create the same response as the unconditioned stimulus (the food) did before the learning.

A third type of implicit memory is known as priming, or changes in behavior as a result of experiences that have happened frequently or recently. Priming refers both to the activation of knowledge (e.g., we can prime the concept of “kindness” by presenting people with words related to kindness) and to the influence of that activation on behavior (people who are primed with the concept of kindness may act more kindly).

One measure of the influence of priming on implicit memory is the word fragment test, in which a person is asked to fill in missing letters to make words. You can try this yourself: First, try to complete the following word fragments, but work on each one for only three or four seconds. Do any words pop into mind quickly?

_ i b _ a _ y

_ h _ s _ _ i _ n

_ o _ k

_ h _ i s _

Now read the following sentence carefully:

“He got his materials from the shelves, checked them out, and then left the building.”

Then try again to make words out of the word fragments.

I think you might find that it is easier to complete fragments 1 and 3 as “library” and “book,” respectively, after you read the sentence than it was before you read it. However, reading the sentence didn’t really help you to complete fragments 2 and 4 as “physician” and “chaise.” This difference in implicit memory probably occurred because as you read the sentence, the concept of “library” (and perhaps “book”) was primed, even though they were never mentioned explicitly. Once a concept is primed it influences our behaviors, for instance, on word fragment tests.

Our everyday behaviors are influenced by priming in a wide variety of situations. Seeing an advertisement for cigarettes may make us start smoking, seeing the flag of our home country may arouse our patriotism, and seeing a student from a rival school may arouse our competitive spirit. And these influences on our behaviors may occur without our being aware of them.

Below, find a video about Clive Wearing – due to brain damage caused by a virus (destroying his hippocampus plus some additional regions), he is largely unable to retrieve old explicit (particularly episodic) memories but has retained some semantic factual memory, as well as implicit procedural memories (like the ability to play the piano). However, he is unable to retain information regarding what is happening for more than about 30 seconds so his sense of consciousness of the world is quite limited in scope. When asked about this, he displays justifiable frustration and sadness around this.

A relatively permanent information storage system that enables one to retain, retrieve, and make use of skills and knowledge hours, weeks, and sometimes years after they were originally learned.

Also: Declarative Memory. Long-term memory that can be consciously recalled: general knowledge or information about personal experiences that an individual retrieves in response to a specific need or request to do so.

The ability to remember personally experienced events associated with a particular time and place.

Memory for general factual knowledge and concepts, of the kind that endows information with meaning and ultimately allows people to engage in such complex cognitive processes as recognizing objects and using language.

A way of measuring quantitatively, without relying on an individual’s conscious memory, how much learned material is retained. In an initial learning session, the number of trials or the amount of time until the individual can achieve a goal, such as one perfect recitation of a list of nonsense syllables, is recorded. At a later time, they are retaught the same material. The difference in number of trials or time taken to achieve the goal is compared between the first and second sessions; this is the savings value (or savings score). Even if the individual has no conscious recollection of the original learning experience (e.g., because of a large time delay between the two sessions), the measurement can still be obtained. Also called the Savings Method.

Memory for a previous event or experience that is produced indirectly, without an explicit request to recall the event and without awareness that memory is involved.

A behaviorist approach to learning in which a neutral stimulus (event) comes to elicit a response through its association with an unconditioned stimulus that naturally produces a behavior.

In cognitive psychology, the effect in which recent experience of a stimulus facilitates or inhibits later processing of the same or a similar stimulus.