6.3 Sentence Parsing

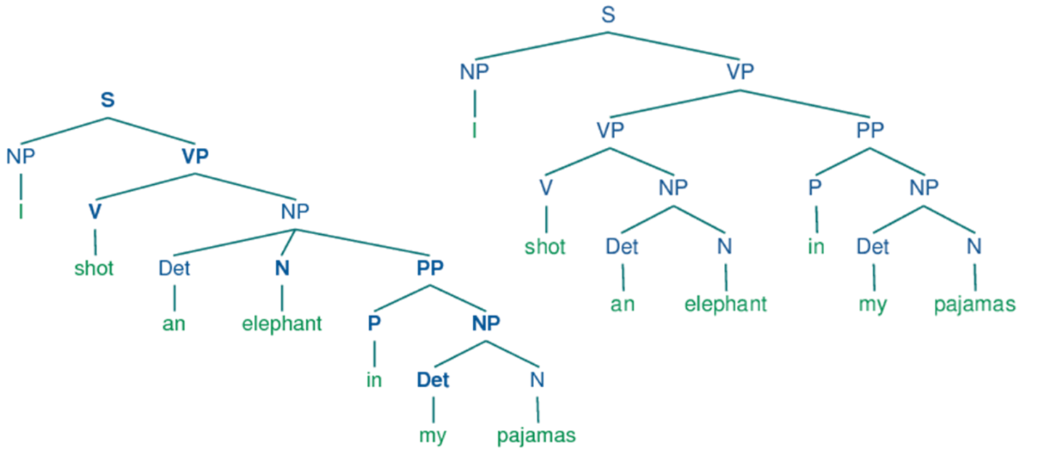

Experiments about how human beings parse (or extract meaning from the component parts of) a sentence often use syntactically ambiguous sentences. This is because it is easier to recognize what sentence-analyzing mechanisms take place when using sentences in which we cannot automatically constitute the meaning of the sentence. Take the two examples below, showing two possible interpretations of the sentence “I shot an elephant in my pajamas.”

A couple theories regarding sentence parsing are discussed below; the syntax-first approach claims that syntax plays the main part whereas semantics has only a supporting role, whereas the interactionist approach states that both syntax and semantics work together to determine the meaning of a sentence.

The Syntax-First Approach of Parsing

The syntax-first approach concentrates on the role of syntax when parsing a sentence. That humans infer the meaning of a sentence based on its syntactical structure (Kako and Wagner 2001) can easily be seen when considering Lewis Carroll´s (1872) poem ‘Jabberwocky’:

“Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe.”

Although most of the words in the poems have no meaning, one may ascribe at least some sense to the poem because of its syntactical structure.

There are many different syntactic rules that are used when parsing a sentence. One important rule is the principle of late closure which means that a person assumes that a new word he perceives is part of the current phrase he is processing. So called “garden-path” sentences offer an example of how this principle may be used in parsing. One example of a garden-path sentence is: “Because he always jogs a mile seems a short distance to him.” When reading this sentence one first wants to continue the phrase “Because he always jogs” by adding “a mile” to the initial phrase, but when reading further one realizes that the words “a mile” are the beginning of a new phrase. This suggests that we sometimes parse a sentence by trying to add new words to a phrase as long as possible.

Garden-path sentences show that we use the principle of late closure as long it syntactically makes sense to add a word to the current phrase. However, when the sentence does not make sense, semantics are often used to rearrange the sentence. The Syntax-First Approach does not disregard semantics; according to this approach, we use syntax first to parse a sentence, and semantics are used afterward to make sense of the sentence.

Apart from experiments showing how syntax is used for parsing sentences, there are also experiments emphasizing how semantics can influence sentence processing. One important experiment about this was done by Daniel Slobin in 1966. He showed that passive sentences are understood faster if the semantics of the words allow only one subject to be the actor. For example, sentences like “The spy saw the man with the binoculars” and “The bird saw the man with the binoculars” are grammatically/syntactically equal. Nevertheless, the first sentence semantically provides two subjects as possible users of binoculars (both the spy and the man can use them) and therefore it takes longer (and requires more context) to parse this sentence. By observing this significant difference in processing time between sentences, it is suggested that semantics also play a significant role in parsing a sentence, lending support to what we will refer to as the Interactionist Approach to parsing.

The Interactionist Approach of Parsing

The interactionist approach ascribes a more central (and earlier) role to semantics in parsing a sentence. In contrast to the syntax-first approach, the interactionist theory claims that syntax is not used first but that semantics and syntax are used simultaneously to parse the sentence and that they work together in clarifying the meaning. There have been several experiments providing evidence that semantics are considered from the beginning when reading a sentence. Many of these experiments utilize eye-tracking techniques and compare the time needed to read syntactically equal sentences in which critical words cause or prohibit ambiguity by semantics. One of these experiments was done by John Trueswell and coworkers in 1994. He measured the eye movement of persons when reading the following two sentences:

“The defendant examined by the lawyer turned out to be unreliable.”

“The evidence examined by the lawyer turned out to be unreliable.”

Trueswell observed that it took longer for participants to read the words “by the lawyer” in the case of the first sentence because in that sentence, the semantics first allow an interpretation in which the defendant is the one who examines, while the evidence (second sentence) can only be examined. This experiment highlights that semantics are also considered while reading the sentence, supporting the Interactionist Approach and weakening the theory that semantics are only considered after a sentence has been parsed syntactically.

An approach to sentence parsing suggesting that syntax processing plays the main role in sentence parsing; humans infer the meaning of a sentence primarily based on syntactical structure.

Contrasted with “syntax-first” sentence parsing. Suggests syntax and semantics are used simultaneously to parse sentences, giving semantics a more central and earlier role in sentence parsing.

When perceiving speech, the idea that a person assumes new incoming words are part of the current phrase being processed. Thus, the current phrase is being closed off “late” in the sequence of processing events.