2.3 Research Considerations and Cautions

Conducting experiments in psychology requires researchers to consider and address some complications in how we conduct the research and how we replicate and report on existing research.

Validity and Reliability

When conducting research, we want to create measures and tasks that have what we refer to as high validity and reliability.

Validity: The extent to which our measure is accurately testing what we want to know about. This has to do with how we operationally define our variables; have we established specific and measurable definitions for our variables so that we know our measures represent the underlying factors we are interested in?

For example, take a reaction time task based on the work of Wundt and Donders (from chapter 1) that is meant to assess reaction speed related to different cognitive demands. Present-day versions of this experiment note that this task can be influenced by age, level of distraction, ability to focus, etc. It’s possible a version of this task might have a goal of measuring cognitive demand but what it is really doing is measuring your ability to focus without getting distracted – this would not have the validity we would quite like.

Reliability: A reliable measure or test is one that gives you consistent results over repeated administrations. If I were a career counselor and had a survey to help you figure out what career you should go into, it would be concerning if you were given different results every time took it. This would result in a low level of confidence in this survey.

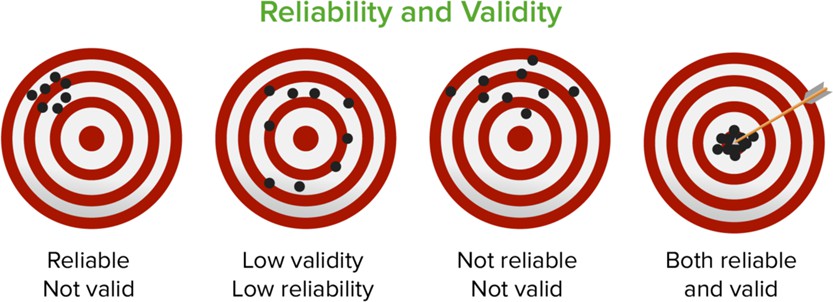

The image below offers a useful visualization. Note that you can have a test that is reliable, but not valid. For example, if a career counseling survey tells you repeatedly that you should be a tight-rope walker in the circus even though you have crippling vertigo, this survey appears to have reliability but not validity. However, for a test to have high validity, it also needs to be reliable.

Ecological Validity

In the effort to make psychology “scientific” and establish cause-and-effect relationships, we control the procedures, environments, and experiences of participants in laboratory experiments. One downside, however, is that as it carefully controls conditions and their effects, experimental research can yield findings that are out of touch with reality and have limited use when trying to understand real-world behavior. Thus, some researchers argue that we lose ecological validity when we rely on artificial environments and tasks for testing. The term ecological validity is used to refer to the degree to which an effect has been obtained under conditions that are typical for what happens in everyday life (Brewer, 2000). The question is: Do our findings in an artificial environment translate (or generalize) to the real world? If we find that, for example, children have difficulty delaying gratification on a controlled task in our lab, can we be confident that they will have difficulty on similar tasks in real life? Or on a broader range of real-life tasks?

Relatedly, here is a short video on the famous Stanford Marshmallow Test addressing issues of ecological validity, validity, and confounding variables.

Replication and Publication Bias

If you recall from our discussion of the research cycle, an important piece of this is for research to be replicated to assess how well the findings hold up. Recently, there has been growing concern as failed attempts to replicate published studies (especially in certain sub-fields of psychology) have become numerous and publicized. Some psychologists frame this as a Replication Crisis, and a more elaborate discussion of this can be found here (Diener & Biswas- Diener, 2024).

Several factors can contribute to this phenomenon:

- Some researchers may have found specific results because their sample size was too small and their findings were the result of random chance.

- In some cases, it could also be that the exact methods and procedures utilized are difficult to recreate.

- More dubiously, there are cases of researchers falsifying their data to achieve desired results (though this appears to be rare).

- It is also possible that for studies done decades ago, the world has changed enough that people have changed along with it! Or more often, that researchers generalized their results from, say, a sample of first-year college students (common research participants in the U.S.) to the human species, and such a conclusion does not hold up when we begin conducting the research across cultures, age groups, etc.

Related to this last point, some researchers (e.g. Henrich et al., 2010) have asserted that historically, Psychology has over-relied on data coming from what they call the WEIRD population – this is an acronym for Western-Educated-Industrialized-Rich-Democratic populations. Psychologists often use college students as participants because they make an easy subject pool, but you run into a problem if you start to assume that everything we’ve learned about college students generalizes to humans more universally. As such, researchers more recently have attempted to replicate foundational studies across broader populations and cultures.

A short video on this from SciShow Psych can be viewed below.

Finally, a related concern is that of Publication Bias. This can happen when the results of an experiment bias the decision to publish the results in a journal. The reality is that year after year, researchers conduct experiments and sometimes, they find statistically significant results that support their hypotheses, and other times they do not. If there is a general bias toward only publishing work that demonstrates “significant” results, then the effects of those experiments may appear stronger than they really are (since researchers in the field are not informed of the attempts where those results were not supported). Think about people posting on social media: If everyone only publicizes when they have great food, fun nights, beautiful sunsets, etc. (which makes sense; who wants to see a picture of my boring veggie wrap that I had for lunch?), then we may start getting the impression that the general population leads more interesting and happier lives than they (and we) do, because we are not given the full (representative) account of their experiences.

Conclusion

Just look at any major news outlet and you’ll find research routinely being reported. Sometimes the journalist understands the research methodology, sometimes not (e.g., correlational evidence is often incorrectly represented as causal evidence). Often, the media are quick to draw a conclusion for you. In order to be a savvy consumer of research, you need to understand the strengths and limitations of different research methods and the distinctions among them. Additionally, you have hopefully gained from this chapter an understanding that the scientific publication process can be flawed, and that it can be beneficial to remain skeptical of some findings until replication bolsters them.

The extent to which our measure is accurately testing what we want to know about.

A reliable measure or test is one that gives you consistent results over repeated administrations.

The degree to which an effect has been obtained under conditions that are typical for what happens in everyday life.

This occurs when the outcome of an experiment or research study biases the decision to publish or otherwise distribute it.