10.6 Problem-Solving by Analogy

Analogies describe similar structures and interconnect them to clarify and explain certain relations. For example, in one study a song that got stuck in your head is compared to an itching of the brain that can only be scratched by repeating the song over and over again.

Restructuring by Using Analogies

If you have figured out one problems via insights from another problem’s solution, you were reasoning by analogy. This analogy heuristic is a useful approach to many real-world problems, and involves trying a solution that solves a similar problem.

One challenge with the analogy approach is to apply solutions from problems that are actually analogous (even when quite different in their surface features)–so-called problem isomorphs–and not applying solutions from problems that appear similar on the surface (e.g., are about similar topics) when the underlying problem structure is actually quite different.

One special kind of restructuring, consistent with a Gestalt approach, is Analogical Reasoning or Analogical Problem Solving. Here, to find a solution to one problem – the so-called target problem, an analogous solution to another problem – the source problem, is presented.

An example of this kind of restructuring, analogical reasoning-problem solving strategy is the Radiation Problem posed by Karl Duncker in 1945:

Radiation and Tumor Problem

“As a doctor you have to treat a patient with a malignant, inoperable tumor, buried deep inside the body. There exists a special kind of ray, which is perfectly harmless at a low intensity, but at the sufficient high intensity is able to destroy the tumor – as well as the healthy tissue on his way to it. What can be done to avoid the latter?”

When this question was asked to participants in experiments (e.g., Duncker, 1945; Gick & Holyoak, 1980, 1983), most of them couldn’t come up with the appropriate answer to the problem. Then participants in Gick & Holyoak’s (1980, 1983) classic studies were told a story that went something like this:

General and Fortress Problem

“A General wanted to capture his enemy’s fortress. He gathered a large army to launch a full-scale direct attack, but then learned, that all the roads leading directly towards the fortress were blocked by mines. These roadblocks were designed in such a way, that it was possible for small groups of the fortress-owner’s men to pass them safely, but every large group of men would initially set them off. Now the General figured out the following plan: He divided his troops into several smaller groups and made each of them march down a different road, timed in such a way, that the entire army would reunite exactly when reaching the fortress and could hit with full strength.”

Here, the story about the General is the source problem, and the radiation problem is the target problem. The fortress is analogous to the tumor and the big army corresponds to the highly intensive ray. Consequently, a small group of soldiers represents a ray at low intensity.

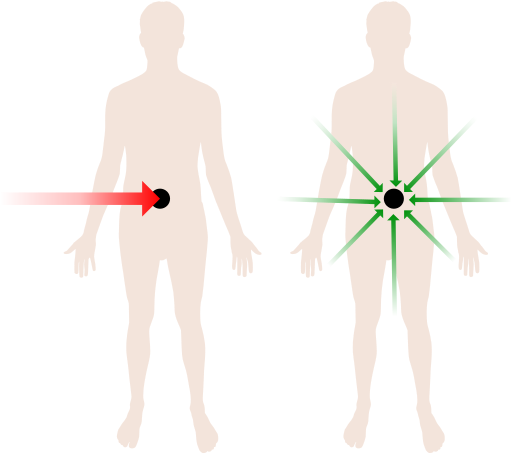

The solution to the target problem is to split the ray up, as the general did with his army, and send the now harmless rays towards the tumor from different angles in such a way that they all meet when reaching it. No healthy tissue is damaged but the tumor itself gets destroyed by the ray at its full intensity.

Gick and Holyoak (1980, 1983) presented Duncker’s radiation problem to groups of participants. Only 10 percent of them were able to solve the problem right away, and 30 percent could solve it when they read the story of the general before. However, after being given an additional hint to use the story as help, 75-92 percent of them solved the problem.

With these results, Gick and Holyoak (1980, 1983) concluded that analogical problem-solving depends on three steps:

- Noticing that an analogical connection exists between the source and the target problem.

- Mapping corresponding parts of the two problems onto each other (e.g. fortress → tumor, army → ray, etc.)

- Applying the mapping to generate a parallel solution to the target problem (e.g. using little groups of soldiers approaching from different directions → sending several weaker rays from different directions)

Next, Gick and Holyoak started looking for factors that could be helpful for the noticing and the mapping parts, for example: Discovering the basic linking concept behind the source and the target problem.

The concept that links the target problem with the analogy (the “source problem“) is called a Problem Schema or Convergence Schema. Gick and Holyoak (1983) triggered the activation of a schema by their participants by giving them two stories and asking them to compare and summarize them. This activation of problem schemas can be called “schema induction.”

One can use an existing common strategy to solve problems of a new kind. To create a good schema and finally get to a solution is a problem-solving skill that requires practice, experience, and some background knowledge. Note that these are also some of the main prerequisites for the acquisition of expertise.

Approach Life’s Problems Differently and Creatively

This is where students chime in again that we just need to “think outside the box” to facilitate creative problem solving in our lives. Maybe. But what does that mean and what would it look like?

Here are 2 readable but very different “how-to” articles for applying these ideas to your own life and approaching life’s problems differently and creatively.