4.6 Levels of awareness

In 1957, a marketing researcher supposedly inserted the words “Eat Popcorn” onto one frame of a film being shown all across the United States. And although that frame was only projected onto the movie screen for 1/24th of a second—a speed too fast to be perceived by conscious awareness—the researcher reported an increase in popcorn sales by nearly 60%. Almost immediately, all forms of “subliminal messaging” were regulated in the US and banned in countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom. Even though it was later shown that the researcher had made up the data (he hadn’t even inserted the words into the film), this fear about influences on our subconscious persists. At its heart, this issue pits various levels of awareness against one another. On the one hand, we have the “low awareness” of subtle, even subliminal influences. On the other hand, there is you—the conscious thinking, feeling you which includes all that you are currently aware of, even reading this sentence. However, when we consider these different levels of awareness separately, we can better understand how they operate.

Low Awareness

You are constantly receiving and evaluating sensory information. Although each moment has too many sights, smells, and sounds for them all to be consciously considered, our brains are nonetheless processing all that information. For example, have you ever been at a party, overwhelmed by all the people and conversation, when out of nowhere you hear your name called? Even though you have no idea what else the person is saying, you are somehow conscious of your name (recall the “cocktail party effect” discussed earlier). So, even though you may not be aware of various stimuli in your environment, your brain is paying closer attention than you think.

Similar to a reflex (like jumping when startled), some cues, or significant sensory information, will automatically elicit a response from us even though we never consciously perceive it. For example, Öhman and Soares (1994) measured subtle variations in sweating of participants with a fear of snakes. The researchers flashed pictures of different objects (e.g., mushrooms, flowers, and most importantly, snakes) on a screen in front of them, but did so at speeds that left the participant clueless as to what he or she had actually seen. However, when snake pictures were flashed, these participants started sweating more (i.e., a sign of fear), even though they had no idea what they’d just viewed!

Although our brains perceive some stimuli without our conscious awareness, do they really affect our subsequent thoughts and behaviors? In a landmark study, Bargh, Chen, and Burrows (1996) had participants solve a word search puzzle where the answers pertained to words about the elderly (e.g., “old,” “grandma”) or something random (e.g., “notebook,” “tomato”).

Afterward, the researchers secretly measured how fast the participants walked down the hallway exiting the experiment. And although none of the participants were aware of a theme to the answers, those who had solved a puzzle with elderly words (vs. those with other types of words) walked more slowly down the hallway!

This effect is called priming (i.e., readily “activating” certain concepts and associations from one’s memory) has been found in a number of other studies. For example, priming people by having them drink from a warm glass (vs. a cold one) resulted in behaving more “warmly” toward others (Williams & Bargh, 2008). Although all of these influences occur beneath one’s conscious awareness, they still have a significant effect on one’s subsequent thoughts and behaviors.

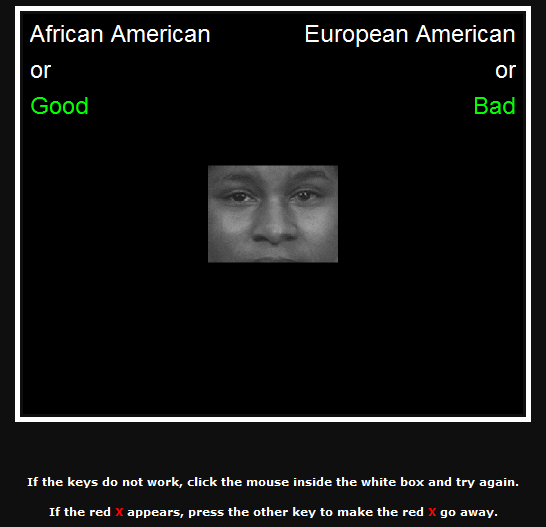

In the last two decades, researchers have made advances in studying aspects of psychology that exist beyond conscious awareness. As you can understand, it is difficult to use self-reports and surveys to ask people about motives or beliefs that they, themselves, might not even be aware of! One way of side-stepping this difficulty can be found in the implicit associations test, or IAT (Greenwald, McGhee & Schwartz, 1998). This research method uses computers to assess

people’s reaction times to various stimuli and is a very difficult test to fake because it records automatic reactions that occur in milliseconds. For instance, to shed light on deeply held biases, the IAT might present photographs of European American faces and Asian faces while asking research participants to click buttons indicating either “good” or “bad” as quickly as possible.

Even if the participant clicks “good” for every face shown, the IAT can still pick up tiny delays in responding. Delays are associated with more mental effort needed to process information.

When information is processed quickly—as in the example of white faces being judged as “good”—it can be contrasted with slower processing—as in the example of Asian faces being judged as “good”—and the difference in processing speed is reflective of bias. In this regard, the IAT has been used for investigating stereotypes (Nosek, Banaji & Greenwald, 2002) as well as self-esteem (Greenwald & Farnam, 2000). This method can help uncover non-conscious biases as well as those that we are motivated to suppress.

High Awareness

Just because we may be influenced by these “invisible” factors, it doesn’t mean we are helplessly controlled by them. The other side of the awareness continuum is known as “high awareness.” This includes effortful attention and careful decision making. For example, when you listen to a funny story on a date, or consider which class schedule would be preferable, or complete a complex math problem, you are engaging a state of consciousness that allows you to be highly aware of and focused on particular details in your environment.

Mindfulness is a state of higher consciousness that includes an awareness of the thoughts passing through one’s head. For example, have you ever snapped at someone in frustration, only to take a moment and reflect on why you responded so aggressively? This more effortful consideration of your thoughts could be described as an expansion of your conscious awareness as you take the time to consider the possible influences on your thoughts. Research has shown that when you engage in this more deliberate consideration, you are less persuaded by irrelevant yet biasing influences, like the presence of a celebrity in an advertisement (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Higher awareness is also associated with recognizing when you’re using a stereotype, rather than fairly evaluating another person (Gilbert & Hixon, 1991).

Humans alternate between low and high thinking states. That is, we shift between focused attention and a less attentive default sate, and we have neural networks for both (Raichle, 2015). Interestingly, the the less we’re paying attention, the more likely we are to be influenced by non- conscious stimuli (Chaiken, 1980). Although these subtle influences may affect us, we can use our higher conscious awareness to protect against external influences. In what’s known as the Flexible Correction Model (Wegener & Petty, 1997), people who are aware that their thoughts or behavior are being influenced by an undue, outside source, can correct their attitude against the bias. For example, you might be aware that you are influenced by mention of specific political parties. If you were motivated to consider a government policy you can take your own biases into account to attempt to consider the policy in a fair way (on its own merits rather than being attached to a certain party).

To help make the relationship between lower and higher consciousness clearer, imagine the brain is like a journey down a river. In low awareness, you simply float on a small rubber raft and let the currents push you. It’s not very difficult to just drift along but you also don’t have total control. Higher states of consciousness are more like traveling in a canoe. In this scenario, you have a paddle and can steer, but it requires more effort.

Understanding Consciousness

Our human consciousness unavoidably colors all of our observations and our attempts to gain understanding. Nonetheless, scientific inquiries have provided useful perspectives on consciousness. The advances described above should engender optimism about the various research strategies applied to date and about the prospects for further insight into consciousness in the future.

Because conscious experiences are inherently private, they have sometimes been taken to be outside the realm of scientific inquiry. This view idealizes science as an endeavor involving only observations that can be verified by multiple observers, relying entirely on the third-person perspective, or the view from nowhere (from no particular perspective). Yet conducting science is a human activity that depends, like other human activities, on individuals and their subjective experiences. A rational scientific account of the world cannot avoid the fact that people have subjective experiences.

Subjectivity thus has a place in science. Conscious experiences can be subjected to systematic analysis and empirical tests to yield progressive understanding. Many further questions remain to be addressed by scientists of the future. Is the first-person perspective of a conscious experience basically the same for all human beings, or do individuals differ fundamentally in their introspective experiences and capabilities? Should psychological science focus only on ordinary experiences of consciousness, or are extraordinary experiences also relevant? Can training in introspection lead to a specific sort of expertise with respect to conscious experience? An individual with training, such as through extensive meditation practice, might be able to describe their experiences in a more precise manner, which could then support improved characterizations of consciousness. Such a person might be able to understand subtleties of experience that other individuals fail to notice, and thereby move our understanding of consciousness significantly forward. These and other possibilities await future scientific inquiries into consciousness.

Priming: the activation of certain thoughts or feelings that make them easier to think of and act upon.

Implicit Associations Test (IAT): A computer reaction time test that measures a person’s automatic associations with concepts. For instance, the IAT could be used to measure how quickly a person makes positive or negative evaluations of members of various ethnic groups.

A state of heightened focus on the thoughts passing through one’s head, as well as a more controlled evaluation of those thoughts (e.g., do you reject or support the thoughts you’re having?).

The ability for people to correct or change their beliefs and evaluations if they believe these judgments have been biased (e.g., if someone realizes they only thought their day was great because it was sunny, they may revise their evaluation of the day to account for this “biasing” influence of the weather).