6.5 Language and Thought: Linguistic Relativity

What are the psychological consequences of language use? When people use language to describe an experience, their thoughts and feelings can be shaped by the linguistic representation that they have produced rather than the original experience per se (Holtgraves & Kashima, 2008). When we speak a language, we use words as representations of ideas, people, places, and events. The given language that children learn is, of course, connected to their culture and surroundings. But can words themselves shape the way we think about things and change our qualitative experience of the world?

Psychologists have long investigated whether language can shape thoughts and actions; a notion called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis or linguistic relativity (Sapir, 1921; Whorf, 1956). Early versions of this hypothesis were quite strong, suggesting, for example, that a person whose community language did not have past-tense verbs would be challenged to think about the past (Whorf, 1956). This strong linguistic determinism view has largely been unsupported, however more recent research has debated (sometimes vigorously) more subtle views.

For instance, some linguistic practices, such as pronoun drop, seem to be associated even with cultural values and social institutions. Pronouns such as “I” and “you” are used to represent the speaker and listener of a speech in English. In an English sentence, these pronouns cannot be dropped if they are used as the subject of a sentence. So, for instance, “I went to the movie last night” is fine, but “Went to the movie last night” is not in standard English. However, in other languages such as Spanish or Japanese, pronouns can be (and in fact often are) dropped from sentences. It turned out that people living in those countries where pronoun drop languages are spoken tend to have more collectivistic values (e.g., placing the good of the group before that of the individual) than those who use non–pronoun drop languages such as English (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). It may be that the explicit reference to “you” and “I” may remind speakers of the distinction between the self and other, and the differentiation between individuals. Such a linguistic practice may act as a constant reminder of the cultural value, which, in turn, may encourage people to perform the linguistic practice. Similar influences of language on cognition can be observed in other domains.

One example of this involves a phenomenon called absolute pitch (AP), in which a listener can identify the musical note label for a sound without requiring any musical context (e.g. hearing an elevator ding and determining that it was an E-flat). Several studies by Diana Deutsch and colleagues have examined the relationship between AP and language experience (as well as musical training). In one such study (Deutsch et al., 2006), researchers found that within musicians, not only were those who started musical training at an early age more likely to have AP than those who started later, but musicians who spoke a tone language (in which the meaning of their utterances varies based on the rising and falling vocal inflections used) like Mandarin Chinese were significantly more likely to have AP than English-speaking musicians. This suggests a connection between language experience and auditory perception (specifically pitch categorization), though it is likely more complicated as additional research suggests a role for working memory capacity in acquiring AP ability (e.g. Van Hedger et al., 2015).

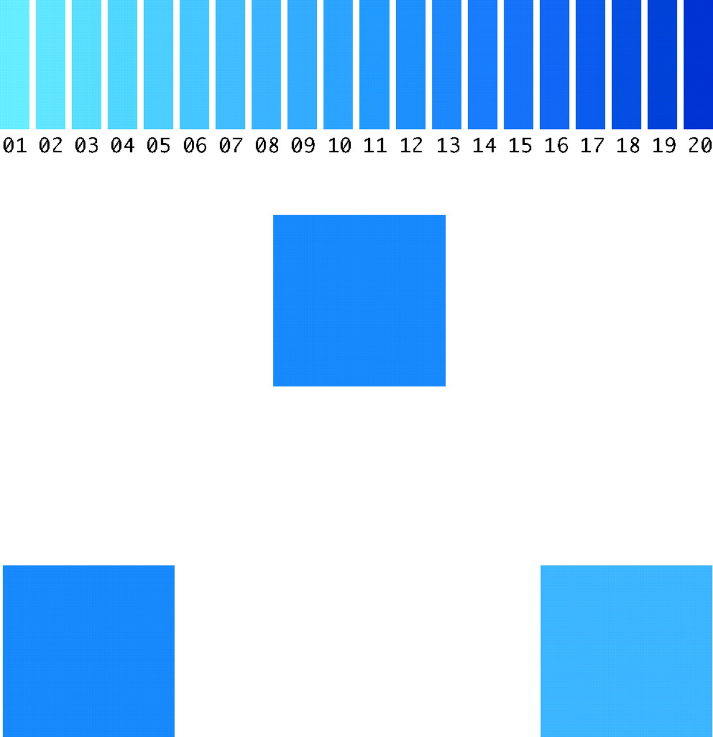

A different line of research involves the influence of language (color labeling systems) on color discrimination. In one such study (Winawer et al., 2007), researchers utilized the different color labeling systems of English and Russian. In English, dark blue and light blue are considered different shades of the same category (and label) blue, but in Russian, they have different labels for lighter blues (“goluboy”) and darker blues (“siniy”). The researchers compared how quickly English and Russian speakers were able to discriminate blue stimuli that spanned the siniy/goluboy categories. They found that on average, Russian speakers were faster to discriminate colors from across the categorical boundary than within color categories. No such difference was found for English speakers given the same stimuli. While this effect has been replicated with some other languages (like English vs. Korean), it also appears to be somewhat more nuanced and task-dependent (e.g. Roberson et al., 2009).

There are additional studies assessing the effects of language in other cognitive and perceptual domains, though the implications are not always clear. For example, Philips and Boroditsky (2003) conducted research suggesting that different grammatical gender categories for inanimate objects (e.g. “spoon” is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish) can influence similarity judgments for person-object pairs across different languages (e.g. Spanish and German). However, this finding has not been consistently replicated – one attempt (Elpers et al., 2022) did not find differences for Spanish and German speakers, but did find that English speakers trained on arbitrary gender-like categories (in which male or female character images were consistently grouped with inanimate objects in made-up categories) rated same-gender person/object pairs as more similar than different-gender person/object pairs. This suggests that in many cases, the effects of language on cognition are complicated at best and require more research to assess the importance of context on the strength of findings.

Find an interesting TED Talk by Lera Boroditsky summarizing several findings in the domain of linguistic relativity below.

See also, Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. The suggestion that our language use (e.g. bilingualism or specific language characteristics) can influence thoughts and actions.

A language in which the meaning of utterances varies based on the pitches