8.3 Eyewitness Testimony and Memory Biases

Eyewitnesses can provide very compelling legal testimony, but rather than recording experiences flawlessly, their memories are susceptible to a variety of errors and biases. They (like the rest of us) can make errors in remembering specific details and can even remember whole events that did not actually happen. In this module, we discuss several of the common types of errors, and what they can tell us about human memory and its interactions with the legal system.

What Is Eyewitness Testimony?

Eyewitness testimony is what happens when a person witnesses a crime (or accident, or other legally important event) and later gets up on the stand and recalls for the court all the details of the witnessed event. It involves a more complicated process than might initially be presumed. It includes what happens during the actual crime to facilitate or hamper witnessing, as well as everything that happens from the time the event is over to the later courtroom appearance. The eyewitness may be interviewed by the police and numerous lawyers, describe the perpetrator to several different people, and make an identification of the perpetrator, among other things.

What can happen to our memory from the time we witness an event to the retelling of that event later? What can influence how we remember, or misremember, highly significant events like a crime or accident? [Image: Robert Couse-Baker, https://goo.gl/OiPUmz, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7]

Why Is Eyewitness Testimony an Important Area of Psychological Research?

When an eyewitness stands up in front of the court and describes what happened from her own perspective, this testimony can be extremely compelling—it is hard for those hearing this testimony to take it “with a grain of salt,” or otherwise adjust its power. But to what extent is this necessary?

There is now a wealth of evidence, from research conducted over several decades, suggesting that eyewitness testimony is probably the most persuasive form of evidence presented in court, but in many cases, its accuracy is dubious. There is also evidence that mistaken eyewitness evidence can lead to wrongful conviction—sending people to prison for years or decades, even to death row, for crimes they did not commit. Faulty eyewitness testimony has been implicated in at least 75% of DNA exoneration cases—more than any other cause (Garrett, 2011). In a particularly famous case, a man named Ronald Cotton was identified by a rape victim, Jennifer Thompson, as her rapist, and was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. After more than 10 years, he was exonerated (and the real rapist identified) based on DNA evidence. For details on this case and other (relatively) lucky individuals whose false convictions were subsequently overturned with DNA evidence, see the Innocence Project website (http://www.innocenceproject.org/).

There is also hope, though, that many of the errors may be avoidable if proper precautions are taken during the investigative and judicial processes. Psychological science has taught us what some of those precautions might involve, and we discuss some of that science now.

Misinformation

In an early study of eyewitness memory, undergraduate subjects first watched a slideshow depicting a small red car driving and then hitting a pedestrian (Loftus, Miller, & Burns, 1978). Some subjects were then asked leading questions about what had happened in the slides. For example, subjects were asked, “How fast was the car traveling when it passed the yield sign?” But this question was actually designed to be misleading, because the original slide included a stop sign rather than a yield sign.

Later, subjects were shown pairs of slides. One of the pair was the original slide containing the stop sign; the other was a replacement slide containing a yield sign. Subjects were asked which of the pair they had previously seen. Subjects who had been asked about the yield sign were likely to pick the slide showing the yield sign, even though they had originally seen the slide with the stop sign. In other words, the misinformation in the leading question led to inaccurate memory.

This phenomenon is called the misinformation effect, because the misinformation that subjects were exposed to after the event (here in the form of a misleading question) apparently contaminates subjects’ memories of what they witnessed. Hundreds of subsequent studies have demonstrated that memory can be contaminated by erroneous information that people are exposed to after they witness an event (see Frenda, Nichols, & Loftus, 2011; Loftus, 2005). The misinformation in these studies has led people to incorrectly remember everything from small but crucial details of a perpetrator’s appearance to objects as large as a barn that wasn’t there at all.

These studies have demonstrated that young adults (the typical research subjects in psychology) are often susceptible to misinformation, but that children and older adults can be even more susceptible (Bartlett & Memon, 2007; Ceci & Bruck, 1995). In addition, misinformation effects can occur easily, and without any intention to deceive (Allan & Gabbert, 2008). Even slight differences in the wording of a question can lead to misinformation effects. Subjects in one study were more likely to say yes when asked “Did you see the broken headlight?” than when asked “Did you see a broken headlight?” (Loftus, 1975).

Other studies have shown that misinformation can corrupt memory even more easily when it is encountered in social situations (Gabbert, Memon, Allan, & Wright, 2004). This is a problem particularly in cases where more than one person witnesses a crime. In these cases, witnesses tend to talk to one another in the immediate aftermath of the crime, including as they wait for police to arrive. But because different witnesses are different people with different perspectives, they are likely to see or notice different things, and thus remember different things, even when they witness the same event. So when they communicate about the crime later, they not only reinforce common memories for the event, they also contaminate each other’s memories for the event (Gabbert, Memon, & Allan, 2003; Paterson & Kemp, 2006; Takarangi, Parker, & Garry, 2006).

The misinformation effect has been modeled in the laboratory. Researchers had subjects watch a video in pairs. Both subjects sat in front of the same screen, but because they wore differently polarized glasses, they saw two different versions of a video, projected onto a screen. So, although they were both watching the same screen, and believed (quite reasonably) that they were watching the same video, they were actually watching two different versions of the video (Garry, French, Kinzett, & Mori, 2008).

In the video, Eric the electrician is seen wandering through an unoccupied house and helping himself to the contents thereof. A total of eight details were different between the two videos. After watching the videos, the “co-witnesses” worked together on 12 memory test questions. Four of these questions dealt with details that were different in the two versions of the video, so subjects had the chance to influence one another. Then subjects worked individually on 20 additional memory test questions. Eight of these were for details that were different in the two videos. Subjects’ accuracy was highly dependent on whether they had discussed the details previously. Their accuracy for items they had not previously discussed with their co-witness was 79%. But for items that they had discussed, their accuracy dropped markedly, to 34%. That is, subjects allowed their co-witnesses to corrupt their memories for what they had seen.

Below, find a TED Talk by Elizabeth Loftus in which she discusses research related to misinformation, including as it pertains to our next topic: identifying perpetrators.

Identifying Perpetrators

In addition to correctly remembering many details of the crimes they witness, eyewitnesses often need to remember the faces and other identifying features of the perpetrators of those crimes. Eyewitnesses are often asked to describe that perpetrator to law enforcement and later to make identifications from books of mug shots or lineups. Here, too, there is a substantial body of research demonstrating that eyewitnesses can make serious, but often understandable and even predictable, errors (Caputo & Dunning, 2007; Cutler & Penrod, 1995).

In most jurisdictions in the United States, lineups are typically conducted with pictures, called photo spreads, rather than with actual people standing behind one-way glass (Wells, Memon, & Penrod, 2006). The eyewitness is given a set of small pictures of perhaps six or eight individuals who are dressed similarly and photographed in similar circumstances. One of these individuals is the police suspect, and the remainder are “foils” or “fillers” (people known to be innocent of the particular crime under investigation). If the eyewitness identifies the suspect, then the investigation of that suspect is likely to progress. If a witness identifies a foil or no one, then the police may choose to move their investigation in another direction.

This process is modeled in laboratory studies of eyewitness identifications. In these studies, research subjects witness a mock crime (often as a short video) and then are asked to make an identification from a photo or a live lineup. Sometimes the lineups are target present, meaning that the perpetrator from the mock crime is actually in the lineup, and sometimes they are target absent, meaning that the lineup is made up entirely of foils. The subjects, or mock witnesses, are given some instructions and asked to pick the perpetrator out of the lineup. The particular details of the witnessing experience, the instructions, and the lineup members can all influence the extent to which the mock witness is likely to pick the perpetrator out of the lineup, or indeed to make any selection at all. Mock witnesses (and indeed real witnesses) can make errors in two different ways. They can fail to pick the perpetrator out of a target present lineup (by picking a foil or by neglecting to make a selection), or they can pick a foil in a target absent lineup (wherein the only correct choice is to not make a selection).

Some factors have been shown to make eyewitness identification errors particularly likely. These include poor vision or viewing conditions during the crime, particularly stressful witnessing experiences, too little time to view the perpetrator or perpetrators, too much delay between witnessing and identifying, and being asked to identify a perpetrator from a race other than one’s own (Bornstein, Deffenbacher, Penrod, & McGorty, 2012; Brigham, Bennett, Meissner, & Mitchell, 2007; Burton, Wilson, Cowan, & Bruce, 1999; Deffenbacher, Bornstein, Penrod, & McGorty, 2004).

It is hard for the legal system to do much about most of these problems. But there are some things that the justice system can do to help lineup identifications “go right.” For example, investigators can put together high-quality, fair lineups. A fair lineup is one in which the suspect and each of the foils is equally likely to be chosen by someone who has read an eyewitness description of the perpetrator but who did not actually witness the crime (Brigham, Ready, & Spier, 1990). This means that no one in the lineup should “stick out,” and that everyone should match the description given by the eyewitness. Other important recommendations that have come out of this research include better ways to conduct lineups, “double blind” lineups, unbiased instructions for witnesses, and conducting lineups in a sequential fashion (see Technical Working Group for Eyewitness Evidence, 1999; Wells et al., 1998; Wells & Olson, 2003).

Encoding Issues

Nobody plans to witness a crime; it is not a controlled situation. There are many types of biases and attentional limitations that make it difficult to encode memories during a stressful event.

Time

When witnessing an incident, information about the event is entered into memory. However, the accuracy of this initial information acquisition can be influenced by a number of factors. One factor is the duration of the event being witnessed. In an experiment conducted by Clifford and Richards (1977), participants were instructed to approach police officers and engage in conversation for either 15 or 30 seconds. The experimenter then asked the police officer to recall details of the person to whom they had been speaking (e.g., height, hair color, facial hair, etc.). The results of the study showed that police had significantly more accurate recall of the 30-second conversation group than they did of the 15-second group. This suggests that recall is better for longer events.

Other-Race Effect

The other-race effect (a.k.a., the own-race bias, cross-race effect, other-ethnicity effect, same- race advantage) is one factor thought to affect the accuracy of facial recognition. Studies investigating this effect have shown that a person is better able to recognize faces that match their own race but are less reliable at identifying other races, thus inhibiting encoding. In the context of signal detection theory, witnesses appear to have more lenient response criterion and thus tend to be more willing to make a positive identification for other-race faces than they are for own-race faces. As a result, they make more false alarms for other-race than own-race faces.

Perception may affect the immediate encoding of these unreliable notions due to prejudices, which can influence the speed of processing and classification of racially ambiguous targets. The ambiguity in eyewitness memory of facial recognition can be attributed to the divergent strategies that are used when under the influence of racial bias.

Weapon-Focus Effect

Weapon focus refers to a factor that affects the reliability of eyewitness testimony. Proponents of this view believe that all the visual attention of the eyewitness gets drawn to the weapon, thereby affecting the ability of the eyewitness to observe other details. The visual attention given by a witness to a weapon can impair his or her ability to make a reliable identification and describe what the culprit looks like if the crime is of short duration.

In a meta-analysis by Nancy Steblay and Elizabeth Loftus (1992), data from various studies on this subject was collected and analyzed to determine if the presence of a weapon may actually be a factor affecting the memory or perception of an eyewitness to a real crime. Of the 19 weapon-focus studies that involved more than 2,000 identifications, Steblay found an average decrease in accuracy of about 10 per cent when a weapon was present. In a separate study, half of the witnesses observed a person holding a syringe in a way that was personally threatening to the witness; the other half saw the same person holding a pen. Sixty-four per cent of the witnesses from the first group misidentified a filler from a target-absent lineup, compared to thirty-three from the second group.

Weapon focus can also affect a witness’s ability to describe a perpetrator. A meta- analysis of ten studies showed that “weapon-absent condition[s] generated significantly more accurate descriptions of the perpetrator than did the weapon-present condition”. Thus, especially when the interaction is brief, the presence of a visible weapon can affect the reliability of an identification and the accuracy of a witness’s description of the perpetrator.

Retrieval Issues

Trials may take many weeks and require an eyewitness to recall and describe an event many times. These conditions are not ideal for perfect recall; memories can be affected by a number of variables.

More Time Issues

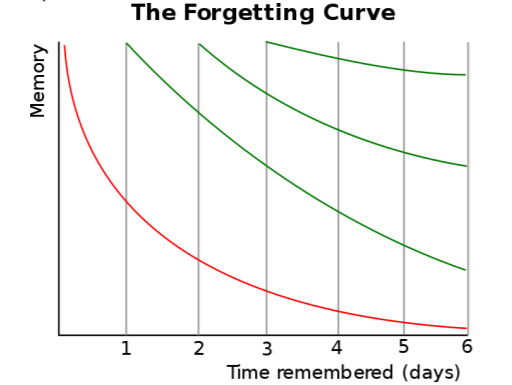

The accuracy of eyewitness memory degrades swiftly after initial encoding. The “forgetting curve” of eyewitness memory shows that memory begins to drop off sharply within 20 minutes following initial encoding, and begins to level off around the second day at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy. Unsurprisingly, research has consistently found that the longer the gap between witnessing and recalling the incident, the less accurately that memory will be recalled. There have been numerous experiments that support this claim. Malpass and Devine (1981) compared the accuracy of witness identifications after 3 days (short retention period) and 5 months (long retention period). The study found no false identifications after the 3-day period, but after 5 months, 35% of identifications were false.

Source Monitoring

One potential error in memory involves mistakes in differentiating the sources of information. Source monitoring refers to the ability to accurately identify the source of a memory. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of wondering whether you really experienced an event or only dreamed or imagined it. If so, you wouldn’t be alone. Rassin, Merkelbach, and Spaan (2001) reported that up to 25% of college students reported being confused about real versus dreamed events. Studies suggest that people who are fantasy-prone are more likely to experience source monitoring errors (Winograd, Peluso, & Glover, 1998), and such errors also occur more often for both children and the elderly than for adolescents and younger adults (Jacoby & Rhodes, 2006).

In other cases we may be sure that we remembered the information from real life but be uncertain about exactly where we heard it. Imagine that you read a news story in a tabloid magazine such as the National Enquirer. Probably you would have discounted the information because you know that its source is unreliable. But what if later you were to remember the story but forget the source of the information? If this happens, you might become convinced that the news story is true because you forget to discount it. The sleeper effect refers to attitude change that occurs over time when we forget the source of information (Pratkanis, Greenwald, Leippe, & Baumgardner, 1988). In the context of eye-witness testimony, this could happen regarding details of a crime (e.g. seeing articles or new stories about the event and confusing them with your own experience) or perhaps the recognition of a suspect (e.g. maybe the suspect is familiar but they could be familiar from a different context).

A phenomenon in which a person mistakenly recalls misleading information that an experimenter has provided, instead of accurately recalling the correct information that had been presented earlier.