5.6 Characterizing mental imagery

The first step to understanding the phenomenon of mental imagery is (or was) simply to establish the characteristics about imagery. And the first approach to this was simply to think about it and ask people about it.

Answering questions about mental imagery requires establishing facts about the phenomena that we can trust and collectively agree upon. However, the subjective aspects of mental imagery present difficulties for objective measurement. Nevertheless, the literature contains methods and findings relevant to mental imagery phenomena, and because of the subjective nature of the topic some skepticism is required for evaluating the results of the research. We begin with the method of introspection.

Methods of Introspection and Subjective report

The technical term for “thinking about it” in Psychology is the method of introspection, which involves self-reflecting upon or scrutinizing aspects of your own cognition. You may be using introspection to think about your own mental imagery experience right now. If you described what those experiences are like, you would be using the method of subjective report. Methods of subjective report remain common today, often in the form of questionnaires that ask people to make various subjective judgments. Although introspection and subjective report have their limitations, they have successfully informed our understanding of mental imagery. We’ll start with an early example.

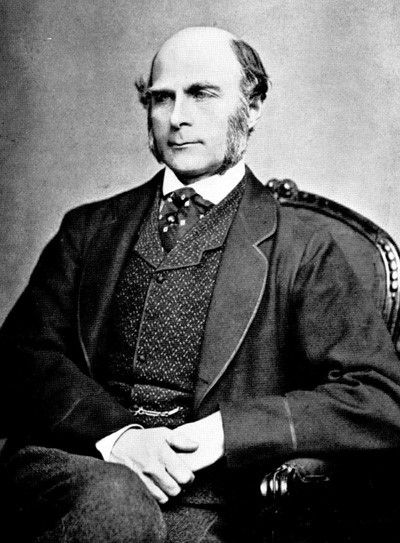

Galton’s Statistics of mental imagery

Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911) was a British psychologist who was one of the first to systematically study mental imagery. To quote from his 1880 paper titled, Statistics of mental imagery (Galton, 1880 – freely available from archive.org), Galton set out to:

“define the different degrees of vividness with which different persons have the faculty of recalling familiar scenes under the form of mental pictures, and the peculiarities of the mental visions of different persons.”

Galton’s Method of Subjective Report

Galton devised the “Breakfast table task” involving a series of structured questions about mental imagery, and sent letters to 100 people asking them to reply with answers to his questions, reprinted here (try it yourself!):

|

Galton’s Breakfast table task questions: |

|

“Before addressing yourself to any of the Questions on the opposite page, think of some definite object – suppose it is your breakfast-table as you sat down to it this morning – and consider carefully the picture that rises before your mind’s eye. |

Galton’s results

Here are some of the answers from “100 men, at least half of whom are distinguished in science or in other fields of intellectual work.” (reprinted from his original manuscript):

|

Cases where the faculty is very high |

|

1. Brilliant, distinct, never blotchy. |

|

2. Quite comparable to the real object. I feel as though I was dazzled, e.g., when recalling the sun to my mental vision. |

|

3. In some instances quite as bright as an actual scene. |

|

Cases where the faculty is mediocre |

|

46. Fairly clear and not incomparable in illumination with that of the real scene, especially when I first catch it. Apt to become fainter when more particularly attended to. |

|

47. Fairly clear, not quite comparable to that of the actual scene. Some objects are more sharply defined than others, the more familiar objects coming more distinctly in my mind. |

|

48. Fairly clear as a general image; details rather misty. |

|

Cases where the faculty is at the lowest |

|

89. Dim and indistinct, yet I can give an account of this morning’s breakfast table; – split herrings, broiled chickens, bacon, rolls, rather light coloured marmalade, faint green plates with stiff pink flowers, the girls’ dresses, &c., &c. I can also tell where all the dishes were, and where the people sat (I was on a visit). But my imagination is seldom pictorial except between sleeping and waking, when I sometimes see rather vivid forms. |

|

90. I am very rarely able to recall any object whatever with any sort of distinctness. Very occasionally an object or image will recall itself, but even then it is more like a generalised image than an individual image. I seem to be almost destitute of visualising power, as under control. |

|

91. My powers are zero. To my consciousness there is almost no association of memory with objective visual impressions. I recollect the breakfast table, but do not see it. |

Galton’s conclusion

Galton’s major conclusion / discovery was that there are considerable individual differences in mental imagery. Some people reported having very strong powers of mental visualization, some people reported having medium abilities, and other people reported having essentially no abilities to visualize anything in their mind’s eye at all.

If we can trust Galton’s results, then the task of explaining mental imagery just got a little bit harder. For example, in addition to explaining how people mentally image things, we also need to explain how some people can do it very well and others can’t do it at all. This is a good example of the increasing complexity that comes along with the research cycle: asking questions uncovers more facts that raise new questions requiring additional explanation.

Limitations with Galton’s method

Galton’s methods were straightforward. He wanted to know how different people experienced mental imagery, so he asked them to think about it and tell him. Although introspection and subjective report were good starting points they also have significant shortcomings. Consider the following limitations: Galton’s participants could have lied about their mental imagery. Their statements could reflect fictional stories rather than facts about mental imagery abilities. The participants may have inaccurately described their own experiences. For example, descriptions could be exaggerated or contain mistaken impressions. People may use different words that suggest larger differences in mental imagery than actually exist.

Establishing facts about mental imagery is difficult because a person’s subjective experience of their own mental imagery is not directly observable by other people. In other domains of inquiry, direct observation can help people quickly establish a set of agreed upon facts. For example, a group of geologists can all look and point at a rock formation, and agree that the rock formation is there, and then proceed to further inspect and measure the rock formation to gather more directly observable facts about it. Galton’s method of subjective report does have some directly observable measurements, such as the words that people used to describe their mental imagery. However, people’s verbal statements are an indirect attempt to communicate an experience, and do not provide an objective lens for other observers to directly view the experience itself.

Obtaining objective facts about subjective experience is undoubtedly a challenge. One way to increase our confidence in scientific facts is to show that they are reproducible. A reproducible finding is one that reliably occurs when an exact or conceptually similar study is repeated by other researchers. So, do Galton’s core claims and findings replicate?

Reproducing Galton’s mental imagery work

Galton conducted his work in the United Kingdom throughout the last half of the 1800s and, like many of his ideas, they spread among psychologists in other countries. At the turn of the century, American psychologists were busy using Galton’s methods and publishing on the mental imagery abilities of college students. In the 1980s, Armstrong (Armstrong Jr, 1894) gave the Breakfast table task to students at Wesleyan University (which, at that time, was a male college). The general pattern of results was similar to what Galton found: The students reported a wide range of mental imagery abilities, including a small proportion of students who were classified as having little to no visual imagery.

In 1902, French (1902) asked students at Vassar college (at that time, a female college) about their mental imagery abilities with a longer mental imagery questionnaire (developed by Titchener, 1905), that was intended to improve upon Galton’s original questions. The results were mostly consistent with prior results, and the Vassar students reported a wide range of different mental imagery abilities. But one finding was not reproduced: All 118 students reported at least some mental imagery abilities, and none reported zero mental imagery abilities. This could mean all of the students happened to have mental imagery abilities, or it could call into question the claims that some people do not have mental imagery. Of course, the results could depend on the questionnaire: Galton had 10 questions about mental imagery, Titchener had almost 90 questions that covered imagery for more senses, which potentially gave students more opportunities to claim that they had at least some mental imagery. Perhaps, Galton and Armstrong would have found all of their participants reporting at least a little bit of mental imagery if they had used the more extensive questionnaire by Titchener.

Aphantasia and Hyperphantasia

Let’s skip ahead a century and ask what recent research on mental imagery looks like. In 2010, Zeman and colleagues reported a case of a patient with “imagery generation disorder” (Zeman et al., 2010) that got picked up in the media. Several people who heard about the finding contacted the researchers to let them know that they also did not experience visual imagery. This led Zeman’s research group to begin examining these claims in more detail and in 2015 they did something very similar to what Galton did; namely, ask people questions about the vividness of their mental imagery (Zeman et al., 2015). They used a newer questionnaire developed to assess the vividness of visual imagery (Marks, 1973) and gave it to people who claimed they had no visual imagery. Perhaps not surprisingly, those same people gave answers to the questionnaire that were consistent with their claims that they had no visual imagery. Zeman coined the term aphantasia to describe the condition of having little to no mental imagery.

The media attention to Zeman’s work on aphantasia caused a great of deal of interest across the world. One of the research participants 2015 study created the Aphantasia Network website, which has grown into a large online community for people with aphantasia. By 2020 (Zeman et al., 2020), Zeman’s group had been contacted by 14,000 people who either claimed they had aphantasia, or the opposite – extremely vivid and life-like mental imagery, termed hyperphantasia. Some of the claims are quite extraordinary. For example, in a 2021 New York Times article (Zimmer, 2021), cognitive neuroscientist Joel Pearson claimed that ‘hyperphantasia could go far beyond just having an active imagination and that “People [with hyperphantasia] watch a movie, and then they can watch it again in their mind, and it’s indistinguishable.”

Most individuals can’t accurately replay a whole movie in their heads. However, there is no shortage of people accomplishing astounding, and objectively verifiable feats of cognition. Daniel Tammet is famous for breaking the European record for correctly reciting, from memory, the first 22,514 digits of the number pi. So, if Daniel Tammet can accurately “replay” the digits of pi for five hours, maybe someone else can replay a whole movie in their mind. Again, the role of direct observation comes into play for lending support to an extraordinary claim. The fact that Daniel could say the digits of pi out loud for other observers to hear, under controlled conditions (where those observers could verify he wasn’t cheating somehow), makes it easier to believe that Daniel’s ability is real. Similarly, if there were more direct methods to test claims about extreme differences in mental imagery abilities, this would lend more support to those claims.

Imagery Across Sensory Modalities

Another fascinating case of incredible cognitive feats can be witnessed through the following Radiolab episode in which they meet Bob Milne. Bob appears capable of “replaying” multiple pieces of music in his head simultaneously, suggesting a vivid “auditory imagery” ability. Interestingly, if you listen to his explanation of how he manages this, there actually appears to be a strong visual imagery component in which he visualizes the musicians.

Taking stock of the facts so far

We have just surveyed a few examples of research into mental imagery abilities. These examples were chosen to highlight some of the challenges with establishing facts about mental imagery, but the larger point is that these challenges apply to the study of many other cognitive abilities as well.

The work we reviewed so far might be best considered as exploratory research – a kind of fact-finding mission. From Galton to Zeman, the questionnaires have been developed to ask “what” questions, rather than “how” questions. And, it is of course useful to establish facts about “what mental imagery is like,” before developing and testing theories about “how mental imagery works.”

What facts about mental imagery can we say have been established by this research? First, we should acknowledge that reasonable people may have different answers to this question. The research we reviewed all used introspection and subjective report methods (questionnaires) to ask people about their own subjective experience of mental imagery.

These methods have limitations as we discussed previously: people might be lying, inaccurate, inattentive, unable to describe their own experience, or describe similar experiences differently. And, of course, the quality of the results is limited by the quality of the measurement tool. It is probably fair to say that these kinds of questionnaire data do not provide clear, objective facts about a person’s internal subjective experience of mental imagery.

But it is also fair to say that this research has produced some objective facts about how people describe their own mental imagery. Across centuries, and thousands of participants, people consistently claim that mental imagery is real for them, and similar proportions of people consistently claim that they have extremely different kinds of mental imagery abilities. So if you were to make your own questionnaire to ask random people on the street about their mental imagery abilities, what do you think would happen given the existing research we discussed? Most likely, you would find the same kinds of results that Galton did in 1880 and Zeman did in the 2010s.

Some takeaways from this slice of the literature:

- Asking people about their own experience can be useful, especially when you want to learn something about their subjective experience.

- People make consistent claims about mental imagery, and provide preliminary forms of subjective evidence about features of their own mental imagery.

- There are limitations due to subjective report, and it would be useful to develop alternative tools to measure different aspects of mental imagery in a more objective way.

Self-reflecting upon or scrutinizing aspects of your own cognition.

The condition of having little to no mental imagery.

Extremely vivid and life-like mental imagery.