9.3 Biases in Our Decision Process

Simon’s concept of bounded rationality taught us that judgment deviates from rationality, but it did not tell us how judgment is biased. Tversky and Kahneman’s (1974) research helped to diagnose the specific systematic, directional biases that affect human judgment. These biases are created by the tendency to short-circuit a rational decision process by relying on a number of simplifying strategies, or “rules of thumb”, known as heuristics. Heuristics allow us to cope with the complex environment surrounding our decisions. Unfortunately, they also lead to systematic and predictable biases.

To highlight some of these biases please answer the questions posed in the following three problems:

|

Problem 1 (adapted from Alpert & Raiffa, 1969) |

|

Listed below are 10 uncertain quantities. Do not look up any information on these items. For each, write down your best estimate of the quantity. Next, put a lower and upper bound around your estimate, such that you are 98 percent confident that your range surrounds the actual quantity. Respond to each of these items even if you admit to knowing very little about these quantities. |

|

Problem 2 (adapted from Joyce & Biddle, 1981) |

|

We know that executive fraud occurs and that it has been associated with many recent financial scandals. And, we know that many cases of management fraud go undetected even when annual audits are performed. Do you think that the incidence of significant executive-level management fraud is more than 10 in 1,000 firms (that is, 1 percent) audited by Big Four accounting firms? |

|

Problem 3 (adapted from Tversky & Kahneman, 1981) |

|

Imagine that the United States is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual avian disease that is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are as follows: |

Overconfidence

On the first problem, if you set your ranges so that you were justifiably 98 percent confident, you should expect that approximately 9.8, or nine to 10, of your ranges would include the actual value. So, let’s look at the correct answers:

- 1901

- 14th of July

- 384,403 km (238,857 mi)

- 56.67 m (183 ft)

- 26,497 (as of 2022)

- 676 people (as of 2023)

- $2.49 billion

- 74.3 years (as of 2019)

- 8,600

- 52

Count the number of your 98% ranges that actually surrounded the true quantities. If you surrounded nine to 10, you were appropriately confident in your judgments. But most readers surround only between three (30%) and seven (70%) of the correct answers, despite claiming 98% confidence that each range would surround the true value. As this problem shows, humans tend to be overconfident in their judgments.

Anchoring

Regarding the second problem, people vary a great deal in their final assessment of the level of executive-level management fraud, but most think that 10 out of 1,000 is too low. When I run this exercise in class, half of the students respond to the question that I asked you to answer. The other half receive a similar problem, but instead are asked whether the correct answer is higher or lower than 200 rather than 10. Most people think that 200 is high. But, again, most people claim that this anchor does not affect their final estimate. Yet, on average, people who are presented with the question that focuses on the number 10 (out of 1,000) give answers that are about one-half the size of the estimates of those facing questions that use an anchor of 200. When we are making decisions, any initial anchor that we face is likely to influence our judgments, even if the anchor is arbitrary. That is, we insufficiently adjust our judgments away from the anchor.

Framing

Turning to Problem 3, most people choose Program A, which saves 200 lives for sure, over Program B. But, again, if I was in front of a classroom, only half of my students would receive this problem. The other half would have received the same set-up, but with the following two options:

|

Problem 3 (for the other half of the participants): |

|

1. Program C: If Program C is adopted, 400 people will die. |

Careful review of the two versions of this problem clarifies that they are objectively the same. Saving 200 people (Program A) means losing 400 people (Program C), and Programs B and D are also objectively identical. Yet, in one of the most famous problems in judgment and decision making, most individuals choose Program A in the first set and Program D in the second set (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). People respond very differently to saving versus losing lives—even when the difference is based just on the framing of the choices.

The problem that I asked you to respond to was framed in terms of saving lives, and the implied reference point was the worst outcome of 600 deaths. Most of us, when we make decisions that concern gains, are risk averse; as a consequence, we lock in the possibility of saving 200 lives for sure. In the alternative version, the problem is framed in terms of losses. Now the implicit reference point is the best outcome of no deaths due to the avian disease. And in this case, most people are risk seeking when making decisions regarding losses.

The availability heuristic

Things that are more easily remembered are judged to be more prevalent. An example for this is an experiment done by Lichtenstein et al. (1978). The participants were asked to choose from two different lists the causes of death which occur more often. Because of the availability heuristic people judged more “spectacular” causes like homicide or tornado to cause more deaths than others, like asthma. The reason for the subjects answering in such a way is that for example films and news in television are very often about spectacular and interesting causes of death. This is why these information are much more available to the subjects in the experiment.

Another effect of the usage of the availability heuristic is called illusory correlations. People tend to judge according to stereotypes. It seems to them that there are correlations between certain events which in reality do not exist. This is what is known by the term “prejudice”. It means that a much oversimplified generalization about a group of people is made. Usually a correlation seems to exist between negative features and a certain class of people (often fringe groups). If, for example, one’s neighbor is jobless and very lazy one tends to correlate these two attributes and to create the prejudice that all jobless people are lazy. This illusory correlation occurs because one takes into account information which is available and judges this to be prevalent in many cases.

The representativeness heuristic

If people have to judge the probability of an event they try to find a comparable event and assume that the two events have a similar probability. Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) presented the following task to their participants in an experiment: “We randomly chose a man from the population of the U.S., Robert, who wears glasses, speaks quietly and reads a lot. Is it more likely that he is a librarian or a farmer?” More of the participants answered that Robert is a librarian which is an effect of the representativeness heuristic. The comparable event which the participants chose was the one of a typical librarian as Robert with his attributes of speaking quietly and wearing glasses resembles this event more than the event of a typical farmer. So, the event of a typical librarian is better comparable with Robert than the event of a typical farmer. Of course this effect may lead to errors as Robert is randomly chosen from the population and as it is perfectly possible that he is a farmer although he speaks quietly and wears glasses.

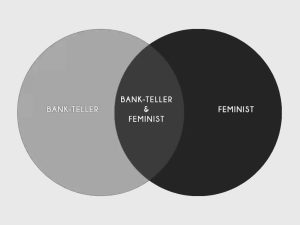

The representativeness heuristic also leads to errors in reasoning in cases where the conjunction rule is violated. This rule states that the conjunction of two events is never more likely to be the case than the single events alone. An example for this is the case of the feminist bank teller (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983). If we are introduced to a woman of whom we know that she is very interested in women’s rights and has participated in many political activities in college and we are to decide whether it is more likely that she is a bank teller or a feminist bank teller, we are drawn to conclude the latter as the facts we have learnt about her resemble the event of a feminist bank teller more than the event of only being a bank teller.

But it is in fact much more likely that somebody is just a bank teller than it is that someone is a feminist in addition to being a bank teller. This effect is illustrated in figure 6 where the green square, which stands for just being a bank teller, is much larger and thus more probable than the smaller violet square, which displays the conjunction of bank tellers and feminists, which is a subset of bank tellers.

The confirmation bias

This phenomenon describes the fact that people tend to decide in terms of what they themselves believe to be true or good. If, for example, someone believes that one has bad luck on Friday the thirteenth, he will especially look for every negative happening at this particular date but will be inattentive to negative happenings on other days. This behavior strengthens the belief that there exists a relationship between Friday the thirteenth and having bad luck.

This example shows that the actual information is not taken into account to come to a conclusion but only the information which supports one’s own belief. This effect leads to errors as people tend to reason in a subjective manner, if personal interests and beliefs are involved. All the mentioned factors influence the subjective probability of an event so that it differs from the actual probability (probability heuristic). Of course all of these factors do not always appear alone, but they influence one another and can occur in combination during the process of reasoning.

Below, find a TED Talk by Dan Gilbert discussing a number of factors that interfere with our ability to make “rational” decisions.

Contemporary Developments

Bounded rationality served as the integrating concept of the field of behavioral decision research for 40 years. Then, in 2000, Thaler (2000) suggested that decision making is bounded in two ways not precisely captured by the concept of bounded rationality. First, he argued that our willpower is bounded and that, as a consequence, we give greater weight to present concerns than to future concerns. Our immediate motivations are often inconsistent with our long-term interests in a variety of ways, such as the common failure to save adequately for retirement or the difficulty many people have staying on a diet. Second, Thaler suggested that our self-interest is bounded such that we care about the outcomes of others. Sometimes we positively value the outcomes of others—giving them more of a commodity than is necessary out of a desire to be fair, for example. And, in unfortunate contexts, we sometimes are willing to forgo our own benefits out of a desire to harm others.

In cognition, an experience-based strategy for solving a problem or making a decision that often provides an efficient means of finding an answer but cannot guarantee a correct outcome.

Anchoring is a reference used when making a series of subjective judgments. For example, in an experiment in which participants gauge distances between objects, the experimenter introduces an anchor by informing the participants that the distance between two of the stimulus objects is a given value. That value then functions as a reference point for participants in their subsequent judgments. Similarly, the options listed for a multiple-choice test item provide an anchor for the test taker to use when answering.

The process of defining the context or issues surrounding a question, problem, or event in a way that serves to influence how the context or issues are perceived and evaluated.

The appearance of a relationship between two variables that does not exist (or is much weaker than assumed).

The conjunction of two events is never more likely to be the case than the single events alone.