7.2 Stages and Types of Memory

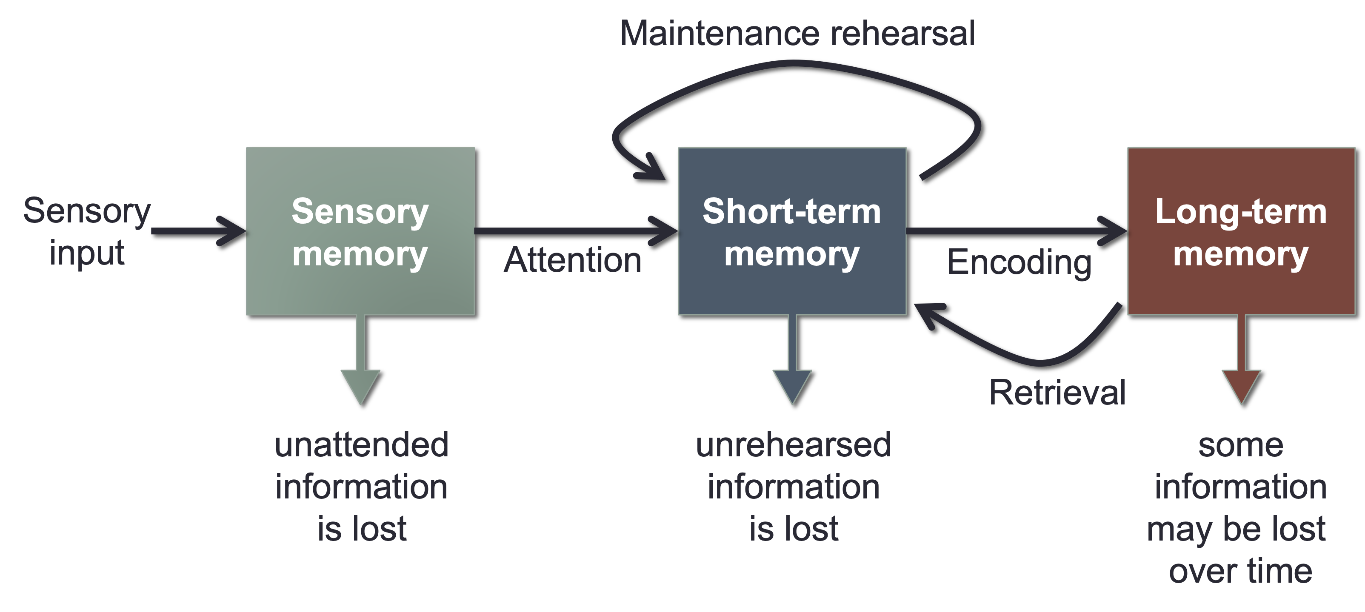

One way of understanding memory is to think about it in terms of stages that describe the length of time that information remains available to us. According to this approach, information begins in sensory memory, moves to short-term memory or working memory, and eventually moves to long-term memory (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968). But not all information makes it through all three stages; most of it is forgotten. Whether the information moves from shorter-duration memory into longer-duration memory or whether it is lost from memory entirely depends on how the information is attended to and processed. Of note is that today, this might function to conceptualize more conscious memory experiences, but there may be information that is processed in parallel (simultaneously) more automatically at a subconscious level, rather than sequentially as indicated here.

Sensory Memory

Sensory memory refers to the brief storage of sensory information. Sensory memory is a memory buffer that lasts only very briefly and then, unless it is attended to and passed on for more processing, is forgotten. Sensory memory gives the brain some time to process incoming sensations and allows us to see the world as an unbroken stream of events rather than as individual pieces.

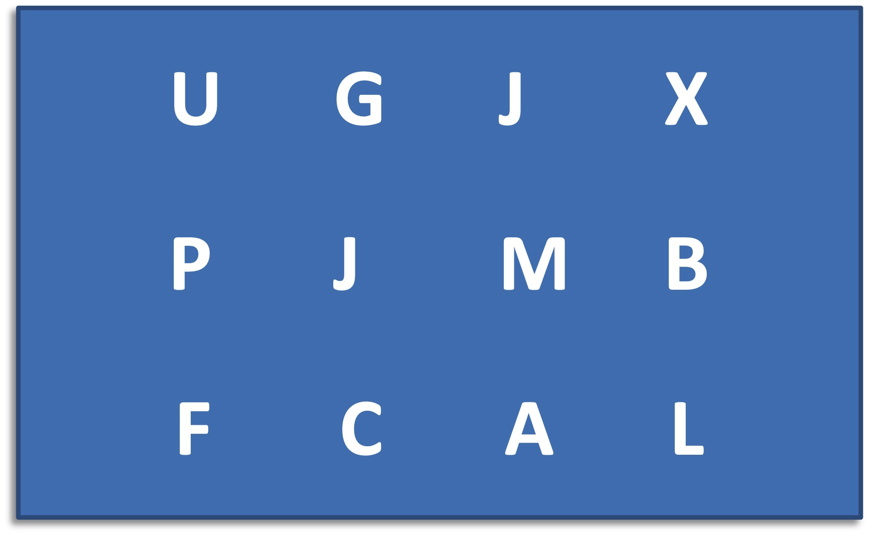

Visual sensory memory is known as iconic memory. Iconic memory was first studied by the psychologist George Sperling (1960). In his research, Sperling showed participants a display of letters in rows, similar to that shown in the figure below. However, the display lasted only about 50 milliseconds (1/20 of a second). Then, Sperling gave his participants a recall test in which they were asked to name all the letters that they could remember (whole report). On average, the participants could remember only three or four of the letters that they had seen.

Sperling reasoned that the participants had seen all the letters but could remember them only very briefly, making it impossible for them to report them all. To test this idea, in his next experiment, he first showed the same letters, but then after the display had been removed, he signaled to the participants to report only the letters from either the first, second, or third row (partial report). In this condition, the participants now reported almost all the letters in that row. This finding confirmed Sperling’s hunch: participants had access to all of the letters in their iconic memories, and if the task was short enough, they were able to report on the part of the display he asked them to. The “short enough” is the length of iconic memory, which turns out to be only a fraction of a second.

Auditory sensory memory is known as echoic memory. In contrast to iconic memories, which decay very rapidly, echoic memories can last as long as four seconds (Cowan, Lichty, & Grove, 1990). This is convenient as it allows you — among other things — to remember the words that you said at the beginning of a long sentence when you get to the end of it, and to take notes on your psychology professor’s most recent statement even after he or she has finished saying it.

In some people iconic memory seems to last longer, a phenomenon known as eidetic imagery (or photographic memory) in which people can report details of an image over long periods of time. These people, who often suffer from psychological disorders such as autism, claim that they can “see” an image long after it has been presented, and can often report accurately on that image. There is also some evidence for eidetic memories in hearing; some people report that their echoic memories persist for unusually long periods of time. The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart may have possessed eidetic memory for music, because even when he was very young and had not yet had a great deal of musical training, he could listen to long compositions and then play them back almost perfectly (Solomon, 1995).

Brief storage of information from each of the senses (in a relatively unprocessed form beyond the duration of a stimulus).

The reproduction, recognition, or recall of a limited amount of material after a period of about 10-30 seconds. STM is often theorized as a separate memory system from long-term memory (LTM).

A more recent conceptualization of short-term memory involved in the brief retention (and retrieval) of information in a highly accessible state. Some researchers have proposed sub-systems of working memory including a phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, central executive, and episodic buffer.

A relatively permanent information storage system that enables one to retain, retrieve, and make use of skills and knowledge hours, weeks, and sometimes years after they were originally learned.

The brief retention of an image of a visual stimulus after the end of the stimulus (typically less than a second).

The retention of auditory information for a brief period (2-3 seconds) after the end of the stimulus.

A clear, specific, high-quality mental image of a visual scene that is retained for a period (second to minutes) after the event.