Chapter 22: Defining Teams & Groups

Chapter Learning Objectives

- 22.1 Differentiate between teams and groups, including their structures, purposes and dynamics. (SLO 1, 2, 4, 5)

- 22.2 Explain the different types of team structures and their potential pros/cons including The Functional Team, a Project Team, Matrix, Contractual and Mixed teams. (SLO 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

- 22.3 Analyze the benefits and challenges of teamwork, including collaboration, conflict resolution and decision-making processes. (SLO 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Our tendency to form groups is a dominant aspect of organizational work. In addition to formal groups, committees, and teams, there are informal groups, cliques, and factions. Every team works slightly different based on the goals, organizational culture and skills each member brings to the group. This chapter will start to establish what a group is, the different types of groups you might experience in business, and success strategies to make a group work.

What is a Group?

Formal groups are used to organize and distribute work, pool information, devise plans, coordinate activities, increase commitment, negotiate, resolve conflicts and conduct inquests. Group work allows the pooling of people’s individual skills and knowledge and helps compensate for individual deficiencies. Estimates suggest most managers spend 50 percent of their working day in one sort of group or another, and for top management of large organizations this can rise to 80 percent. Thus, formal groups are clearly an integral part of the functioning of an organization.

No less important are informal groups. These are usually structured more around the social needs of people than around the performance of tasks. However, these informal groups may also have an important effect on formal work tasks. For example, by exerting subtle pressures on group members to conform to a particular work rate, or as ‘places’ where news, gossip, etc., is exchanged.

Watch this video to help learn about when a group of people stops being a group of people and starts being a team: “Are you a true team or just a mere group?”

Video: What is Teamwork

What is a Team?

You probably described a team as a group of some kind. However, a team is more than just a group. When you think of all the groups that you belong to, you will probably find that very few of them are really teams. Some of them will be family or friendship groups that are formed to meet a wide range of needs such as affection, security, support, esteem, belonging, or identity. Some may be committees whose members represent different interest groups and who meet to discuss their differing perspectives on issues of interest.

In this reading, the term ‘work group’ (or ‘group’) is often used interchangeably with the word ‘team,’ although a team may be thought of as a particularly cohesive and purposeful type of work group. We can distinguish work groups or teams from more casual groupings of people by using the following set of criteria. A collection of people can be defined as a work group or team if it shows most, if not all, of the following characteristics.

Click on each heading to see the characteristics of a team:

Usually, the tasks and goals set by teams cannot be achieved by individuals working alone because of constraints on time and resources, and because few individuals possess all the relevant competences and expertise. Sports teams or orchestras clearly fit these criteria.

By contrast, many groups are much less explicitly focused on an external task. In some instances, the growth and development of the group itself is its primary purpose; process is more important than outcome. Many groups are reasonably fluid and less formally structured than teams. In the case of work groups, an agreed and defined outcome is often regarded as a sufficient basis for effective cooperation and the development of adequate relationships.

Teamwork is usually connected with project work, and this is a feature of much work. Teamwork is particularly useful when you must address risky, uncertain, or unfamiliar problems where there is a lot of choice and discretion surrounding the decision to be made. In the area of voluntary and unpaid work, where pay is not an incentive, teamwork can help to motivate support and commitment because it can offer the opportunities to interact socially and learn from others. Furthermore, people are more willing to support and defend the work they helped create.

Importantly, groups and teams are not distinct entities. Both can be pertinent in personal development as well as organizational development and management change. In such circumstances, when is it appropriate to embark on teambuilding rather than relying on ordinary group or solo working?

In general, the greater the task uncertainty the more important teamwork is, especially if it is necessary to represent the differing perspectives of concerned parties. In such situations, the facts themselves do not always point to an obvious policy or strategy for innovation, support, and development: decisions are partially based on the opinions and the personal visions of those involved.

Risks of Teamwork

There are risks associated with working in teams as well. Under some conditions, teams may produce more conventional, rather than more innovative, responses to problems. The reason for this is that team decisions may regress towards the average, with group pressures to conform cancelling out more innovative decision options. It depends on how innovative the team is, in terms of its membership, its norms, and its values.

Teamwork may also be inappropriate when you want a fast decision. Team decision making is usually slower than individual decision making because of the need for communication and consensus about the decision taken. For example, despite the business successes of Japanese companies, it is now recognized that promoting a collective organizational identity and responsibility for decisions can sometimes slow down operations significantly, in ways that are not always compensated for by better decision making.

There may be times when simply working alone is more appropriate and more effective. For example, if an individual has enough expertise to make a decision on their own and the deadline is tight, working alone might be the better choice. Some may argue that groups and teams may produce conventional rather than innovative responses to problems, because decisions may regress towards the average of the members. But depending on the group, brainstorming activities can help teams put different ideas together to select more creative decisions. Every team operates differently, so the decision of whether a team is the best choice is unique to each situation.

In general, the greater the task uncertainty, the more important it will be to work in a group or team rather than individually. The less obvious and more complex the task is, the more important a team can be. This is because there will be a greater need for different skills and perspectives, especially if it is necessary to represent the different perspectives of the different stakeholders involved.

Click on the following headings to see different reasons to work alone or in teams and reasons to work in structured teams:

Types of Teams

Different organizations or organizational settings lead to different types of teams. The type of team affects how that team is managed, what the communication needs of the team are and, where appropriate, what aspects of the project the project manager needs to emphasize.

A work group or team may be permanent, forming part of the organization’s structure, such as a top management team. They may also be temporary, such as a task force assembled to see through a particular project. Members may work continuously or meet only intermittently. The more direct contact and communication team members have with each other, the more likely they are to function well as a team. Thus, getting a group of individuals to function well together is a valuable management aim.

The following section defines common types of teams. Many teams may not fall clearly into one type but may combine elements of different types. Many organizations have traditionally been managed through a hierarchical structure with defined roles and reporting requirements.

The number of levels in the hierarchy of a team depends upon the size and to some extent on the type of organization. The span of control is the number of people each manager or supervisor is directly responsible for and varies widely. As a general rule in business, it is difficult practice for any single manager to supervise more than 7-10 people.

While the hierarchy is designed to provide a stable ‘backbone’ to the organization, projects are primarily concerned with change and so tend to be organized quite differently. Their structure needs to be more fluid than that of conventional management structures. There are four commonly used types of project team: the functional team, the project (single) team, the matrix team and the contract team.

The Functional Team

The hierarchical structure described above divides groups of people along largely functional lines: people working together carry out the same or similar functions. A functional team is a team in which work is carried out within a group organized around a similar function or task. This can be project work. In organizations in which the functional divisions are relatively rigid, project work can be handed from one functional team to another in order to complete the work.

For example, work on a new product can pass from marketing, which has the idea, to research and development, which sees whether it is technically feasible, thence to design and finally manufacturing. This is sometimes known as ‘baton passing’ – or, less flatteringly, as ‘throwing it over the wall’!

Project or Single Team

The project, or single, team consists of a group of people who come together as a distinct organizational unit to work on a project or projects. The team is often led by a project manager, though self-managing and self-organizing arrangements are also found. Quite often, a team that has been successful on one project will stay together to work on subsequent projects.

This is particularly common where an organization engages repeatedly in projects of a broadly similar nature – for example developing software, or in construction. Perhaps the most important issue in this instance is to develop the collective capability of the team, since this is the currency for continued success. “People issues” are often crucial in achieving continued success.

The closeness of the dedicated project team normally reduces communication problems within the team. However, care should be taken to ensure that communications with other stakeholders (senior management, line managers and other members of staff in the departments affected, and so on) are not neglected, as it is easy for ‘us and them’ distinctions to develop.

Matrix Team

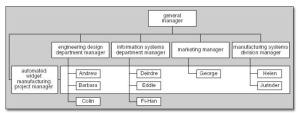

In a matrix team, staff report to different managers on different aspects of their work. Matrix structures are often, but not exclusively, found in projects. Matrix structures are more common in large and multi-national organizations. In this structure, staff are responsible to the project manager for their work on the project while their functional line manager may be responsible for other aspects of their work such as appraisal, training, and career development, and ‘routine’ tasks. Notice how the traditional hierarchy is cross-cut by the ‘automated widget manufacturing configuration.’

In this form of organization, staff from various functional areas (such as design, software development, manufacturing or marketing) are loaned or seconded to work on a particular project. Such staff may work full- or part-time on the project. The project manager thus has a recognizable team and is responsible for controlling and monitoring its work on the project.

However, many of the project staff will still have other duties to perform in their normal functional departments. The functional line managers they report to will retain responsibility for this work and for the professional standards of their work on the project, as well as for their training and career development. It is important to overcome the problems staff might have with the dual reporting lines (the ‘two-boss’ problem). This requires building good interpersonal relationships with the team members and regular, effective communication.

Contract Team

The contract team is brought in from outside to do the project work. Here, the responsibility to deliver the project rests very firmly with the project manager. The client will find such a team harder to control directly. On the other hand, it is the client who will judge the success of the project, so the project manager has to keep an eye constantly on the physical outcomes of the project. A variant of this is the so-called ‘outsourced supply team’, which simply means that the team is physically situated remotely from the project manager, who then encounters the additional problem of ‘managing at a distance’.

Mixed Structures

Some teams have mixed structures depending on the specifics of the goal and the organization. Some members may be employed to work full-time on the project and be fully responsible to the project manager. Project managers themselves are usually employed full-time.

Others may work part time and be responsible to the project manager only during their time on the project. For example, internal staff may well work on several projects at the same time. Alternatively, an external consultant working on a given project may also be involved in a wider portfolio of activities.

Some may be part of a matrix arrangement, whereby their work on the project is overseen by the project manager and they report to their line manager for other matters. Project administrators often function in this way, serving the project for its duration, but having a career path within a wider administrative service.

Still others may be part of a functional hierarchy, undertaking work on the project under their line manager’s supervision by negotiation with their project manager. For instance, someone who works in an organization’s legal department may provide the project team with access to legal advice when needed.

In relatively small projects the last two arrangements are a very common way of accessing specialist services that will only be needed from time to time.

Modern Teams

In addition to the traditional types of teams or groups outlined above, recent years have seen the growth of interest in three other important types of team: ‘self-managed teams’, ‘self-organizing teams’, and ‘dispersed virtual teams.’

A typical self-managed team may be permanent or temporary. It operates in an informal and non-hierarchical manner and has considerable responsibility for the way it carries out its tasks. It is often found in organizations that are developing total quality management and quality assurance approaches.

In contrast, organizations that deliberately encourage the formation of self-organizing teams are comparatively rare. Teams of this type can be found in highly flexible, innovative organizations that thrive on creativity and informality. These are modern organizations that recognize the importance of learning and adaptability in ensuring their success and continued survival. However, self-organizing teams exist, unrecognized, in many organizations. For instance, in traditional, bureaucratic organizations, people who need to circumvent the red tape may get together in order to make something happen and, in so doing, spontaneously create a self-organizing team. The team will work together, operating outside the formal structures, until its task is done and then it will disband.

Many organizations set up self-managed or empowered teams as an important way of improving performance and they are often used as a way of introducing a continuous improvement approach. These teams tend to meet regularly to discuss and put forward ideas for improved methods of working or customer service in their areas.

Some manufacturers have used multi-skilled self-managed teams to improve manufacturing processes, to enhance worker participation and improve morale. Self-managed teams give employees an opportunity to take a more active role in their working lives and to develop new skills and abilities. This may result in reduced staff turnover and less absenteeism.

Self-organizing teams are usually formed spontaneously in response to an issue, idea or challenge. This may be the challenge of creating a radically new product or solving a tough production problem. In Japan, the encouragement of self-organizing teams has been used as a way of stimulating discussion and debate about strategic issues so that radical and innovative new strategies emerge. By using a self-organizing team approach companies were able to tap into the collective wisdom and energy of interested and motivated employees.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual teams are increasingly common. A virtual team is one whose primary means of communicating is electronic, with only occasional phone and face-to-face communication, if at all. Virtual teams use technologies like, Zoom, Teams, Google Meet, etc. to coordinate, meet, and share work. Table 3 contains a summary of benefits virtual groups provide to organizations and individuals, as well as the potential challenges and disadvantages virtual groups present.

Teams have organizational and individual benefits, as well as possible challenges and disadvantages. Click on each heading to see the benefits and disadvantages:

Group Development

In most cases groups do not become smooth-functioning teams overnight. As Bruce Tuckman’s (1965) theory of group development suggests, groups usually pass through several stages of development as they change from a newly formed group into an effective team:

Stage 1 – “Forming”. Members become oriented toward one another and expose information about themselves in polite but tentative interactions. They explore the purposes of the group and gather information about each other’s interests, skills, and personal tendencies.

Stage 2 – “Storming”. The group members find themselves in conflict, and some solution is sought to improve the group environment. Disagreements about procedures and purposes surface, so criticism and conflict increase. Much of the conflict stems from challenges between members who are seeking to increase their status and control in the group.

Stage 3 – “Norming”. Standards for behavior and roles develop that regulate behavior. Once the group agrees on its goals, procedures, and leadership, norms, roles, and social relationships develop that increase the group’s stability and cohesiveness.

Stage 4 – “Performing”. The group has reached a point where it can work as a unit to achieve desired goals. The group focuses its energies and attention on its goals, displaying higher rates of task-orientation, decision-making, and problem-solving.

Stage 5 – “Adjourning”. The sequence of development ends and the group disbands. The group prepares to disband by completing its tasks, reduces levels of dependency among members, and dealing with any unresolved issues.

Sources based on Tuckman (1965) and Tuckman & Jensen (1977)

We also experience change as we pass through a group: We don’t become full-fledged members of a group in an instant. Instead, we gradually become a part of the group and remain in the group until we leave it. Moreland and Levine’s (1982) model of group socialization describes this process, beginning with initial entry into the group and ending when the member exits it.

For example, when you are thinking of joining a new group—a social club, a professional society, a fraternity or sorority, or a sports team—you investigate what the group has to offer, but the group also investigates you. During this investigation stage you are still an outsider: interested in joining the group but not yet committed to it in any way.

But once the group accepts you and you accept the group, socialization begins you learn the group’s norms and take on different responsibilities depending on your role. On a sports team, for example, you may initially hope to be a star who starts every game or plays a particular position, but the team may need something else from you. In time, though, the group will accept you as a full-fledged member and both sides in the process—you and the group itself—increase their commitment to one another. When that commitment wanes, however, your membership may come to an end as well.

Team Effectiveness

Clearly, there are no hard-and-fast rules which lead to team effectiveness. The determinants of a successful team are complex and not equivalent to following a set of prescriptions. However, the results of poor teamwork can be expensive, so it is useful to draw on research, experience and case studies to explore some general guidelines.

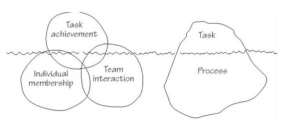

Borrowing from Adair’s (1983) leadership model, the elements of a team can be shown as an iceberg in the water. Superficial observation of teams in organizations might suggest that most, if not all, energy is devoted to the explicit task (what is to be achieved, by when, with what budget and what resources). Naturally, this is important. But too often the concealed part of the iceberg (how the team will work together) is neglected. As with real icebergs, shipwrecks can ensue.

The main constituents of team effectiveness are on the left side of the image: Task Achievement, Individual Membership and Team Interaction. These elements overlapping with Task Achievement being what is “visible” on top of the water line to those not on the team. For example, team member satisfaction will be derived not only from the achievement of tasks but also from the quality of team relationships and the more social aspects of teamworking: people who work almost entirely on their own, such as teleworkers and self-employed business owner-managers, often miss the opportunity to bounce ideas off colleagues in team situations. The experience of solitude in their work can, over time, create a sense of isolation, and impair their performance. The effectiveness of a team should also relate to the next step, to what happens after the achievement of team goals.

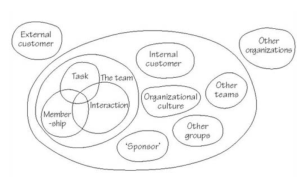

In addition to what happens inside a team there are external influences that impact upon team operations. Teams operate in complex systems composed of both internal and external stakeholders, resources, and outcomes. We don’t fully understand the complexity of these interactions and combinations. The best that we can start to understand each factor is to discuss each item in turn and consider some of the interactions as they relate to team effectiveness.

For instance, discussions about whether the wider culture of an organization supports and rewards teamworking, whether a team’s internal and/or external customers clearly specify their requirements and whether the expectations of a team match those of its sponsor will all either help or hinder a team’s ongoing vitality.

Groupthink

Groups sometimes make spectacularly bad decisions. In 1961, a special advisory committee to President John F. Kennedy planned and implemented a covert invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs that ended in total disaster. In 1986, NASA carefully, and incorrectly, decided to launch the Challenger space shuttle in temperatures that were too cold.

Irving Janis (1982), intrigued by these kinds of blundering groups, carried out a number of case studies of such groups: the military experts that planned the defense of Pearl Harbor; Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs planning group; the presidential team that escalated the war in Vietnam. Each group, he concluded, fell prey to a distorted style of thinking that rendered the group members incapable of making a rational decision. Janis labeled this syndrome groupthink: “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action” (p. 9).

Janis identified both the telltale symptoms that signal the group is experiencing groupthink and the interpersonal factors that combine to cause groupthink. These symptoms include overestimating the group’s skills and wisdom, biased perceptions and evaluations of other groups and people who are outside of the group, strong conformity pressures within the group, and poor decision-making methods.

Janis also singled out four group-level factors that combine to cause groupthink: cohesion, isolation, biased leadership, and decisional stress.

- Cohesion: Groupthink only occurs in cohesive groups. Such groups have many advantages over groups that lack unity. People enjoy their membership much more in cohesive groups, they are less likely to abandon the group, and they work harder in pursuit of the group’s goals. But extreme cohesiveness can be dangerous. When cohesiveness intensifies, members become more likely to accept the goals, decisions, and norms of the group without reservation. Conformity pressures also rise as members become reluctant to say or do anything that goes against the grain of the group, and the number of internal disagreements—necessary for good decision making—decreases.

- Isolation. Groupthink groups too often work behind closed doors, keeping out of the limelight. They isolate themselves from outsiders and refuse to modify their beliefs to bring them into line with society’s beliefs. They avoid leaks by maintaining strict confidentiality and working only with people who are members of their group.

- Biased leadership. A biased leader who exerts too much authority over group members can increase conformity pressures and railroad decisions. In groupthink groups, the leader determines the agenda for each meeting, sets limits on discussion, and can even decide who will be heard.

- Decisional stress. Groupthink becomes more likely when the group is stressed, particularly by time pressures. When groups are stressed, they minimize their discomfort by quickly choosing a plan of action with little argument or dissension. Then, through collective discussion, the group members can rationalize their choice by exaggerating the positive consequences, minimizing the possibility of negative outcomes, concentrating on minor details, and overlooking larger issues.

Groupthink, thus, represents an issue with group process. Members in groups that fall victim to groupthink do not spend enough time, energy, or effort on meaningful process (Kramer & Dougherty, 2013). It is also important to note that cohesion alone is not sufficient to prompt groupthink. Teams who are vigilant against biased decision making can avoid problematic groupthink process.

Conclusion

Groups and teams in business and many aspects of our lives. They can be organized in various structures depending on the role and goals. There are pros and cons to teamwork and not every team may be successful, though there are many strategies leaders or managers or team members can take to contribute to reaching the ultimate goal.

How to cite this chapter:

Piercy, C. (2021). Chapter 22: Defining Teams and Groups. In Pouska, B. (Ed.), Business Professionalism. New Mexico Open Educational Resources Consortium Pressbooks. https://nmoer.pressbooks.pub/businessprofessionalism/

Licenses and Attributions

References

Adair, J. (1983). Effective leadership. Gower.

Industrial Society. (1995). Managing best practice: Self-managed teams (Publication No. 11). Industrial Society.

Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., … & Van Vugt, M. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

Makin, P., Cooper, C., & Cox, C. (1989). Managing people at work. The British Psychological Society and Routledge.

SACS Consulting. (2024). Are you a true team or just a mere group? – What is teamwork part 2 [Video]. YouTube. (Licensed under Standard YouTube License – All Rights Reserved.)

Stanton, A. (1992). Learning from experience of collective teamwork. In R. Paton, C. Cornforth, & J. Batsleer (Eds.), Issues in voluntary and non-profit management (pp. 95–103). Addison-Wesley.

Piercy, C. W., & Kramer, M. W. (2017). Exploring dialectical tensions of leading volunteers in two community choirs. Communication Studies, 68(2), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2017.1299023

Original Chapter Source

Original chapter source: Adapted from Problem Solving in Teams and Groups by Cameron W. Piercy, PhD.