Chapter 16: Conflict and Negotiation

Chapter Learning Objectives

- 16.1 Explain the importance of professionalism, courtesy, and emotional control in maintaining a respectful and productive workplace environment. (SLO 1, 2, 5)

- 16.2 Apply strategies for handling workplace challenges such as criticism, conflict, or stress with grace, discretion and emotional intelligence. (SLO 1, 2)

- 16.3 Evaluate different approaches to managing difficult situations at work, including how to respond to gossip, maintain confidentiality, and balance authenticity with professionalism. (SLO 1, 2, 4, 5)

Conflict is a powerful part of human interaction, including among groups and teams. In this chapter, we will define conflict, consider whether conflict is functional or dysfunctional, discuss the conflict process, and identify strategies for preventing and reducing conflict in groups.

Definitions for Conflict

Conflict is an expressed struggle between interdependent parties over goals which they perceive as incompatible or resources which they perceive to be insufficient. Let’s examine the ingredients in their definition.

First of all, conflict must be expressed. If two members of a group dislike each other or disagree with each other’s viewpoints but never show those sentiments, there’s no conflict.

Second, conflict takes place between or among parties who are interdependent—that is, who need each other to accomplish something. If they can get what they want without each other, they may differ in how they do so, but they won’t come into conflict.

Finally, conflict involves clashes over what people want or over the means for them to achieve it. Party A wants X, whereas party B wants Y. If they either can’t both have what they want at all, or they can’t each have what they want to the degree that they would prefer to, conflict will arise.

The Positive and Negative Sides of Conflict

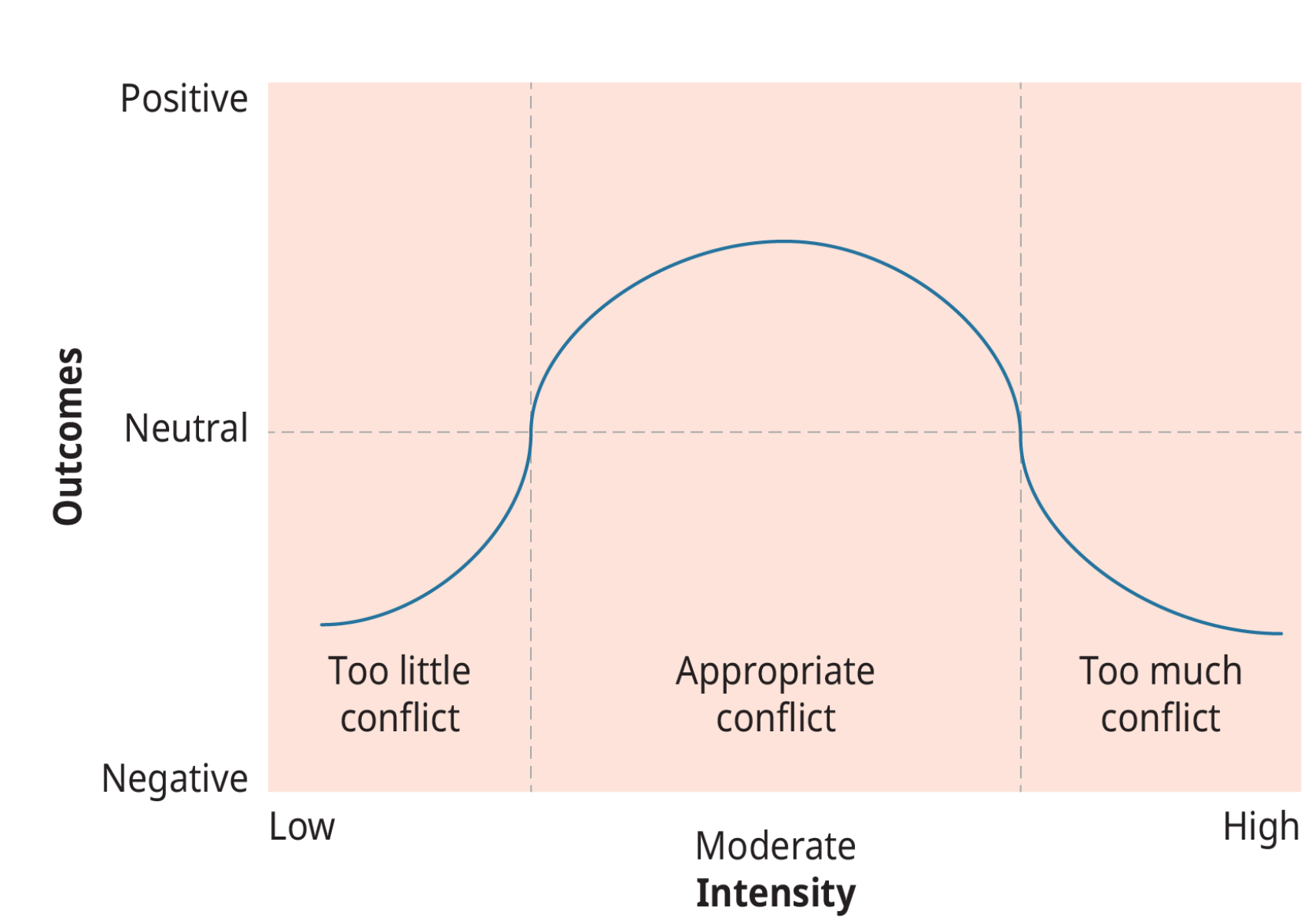

There are some circumstances in which a moderate amount of conflict can be helpful. For example, conflict can stimulate innovation and change. Conflict can help individuals and group members grow and develop self-identities.

Conflict can have negative consequences when people divert energies away from performance and goal attainment and direct them toward resolving the conflict. Continued conflict can take a heavy toll in terms of psychological well-being. Conflict has a major influence on stress and the psychophysical consequences of stress. Finally, continued conflict can also affect the social climate of the group and inhibit group cohesiveness.

Thus, conflict can be either functional or dysfunctional depending upon the nature of the conflict, its intensity, and its duration. Indeed, both too much and too little conflict can lead to a variety of negative outcomes, as discussed above. In such circumstances, a moderate amount of conflict may be the best course of action. The issue for groups, therefore, is not how to eliminate conflict but rather how to manage and resolve it when it occurs.

Types of Conflict

Group conflicts may deal with many topics, needs, and elements. Kelly (2006) identified the following five types of conflict:

First, there are conflicts of substance. These conflicts, which relate to questions about what choices to make in each situation, rest on differing views of the facts. For example, if a student thinks the biology assignment requires an annotated bibliography but another student believes a simple list of readings will suffice, they are in a conflict of substance. Another term for this kind of conflict is “intrinsic conflict.”

Conflicts of value are those in which various parties either hold totally different values or rank the same values in a significantly different order. The famous sociologist Milton Rokeach (1979), for instance, found that freedom and equality constitute values in the four major political systems of the past 100 years—communism, fascism, socialism, and capitalism. What differentiated the systems, however, was the degree to which proponents of each system ranked those two key values. According to Rokeach’s analysis, socialism holds both values highly; fascism holds them in low regard; communism values equality over freedom, and capitalism values freedom over equality. As we all know, conflict among proponents of these four political systems preoccupied people and governments for the better part of the twentieth century.

Conflicts of process arise when people differ over how to reach goals or pursue values which they share. How closely should they stick to rules and timelines, for instance, and when should they let their hair down and simply brainstorm new ideas? What about when multiple topics and challenges are intertwined; how and when should the group deal with each one? Another term for these disputes is “task conflicts.”

Conflicts of misperceived differences come up when people interpret each other’s actions or emotions erroneously. You can probably think of several times in your life when you first thought you disagreed with other people but later found out that you’d just misunderstood something they said and that you actually shared a perspective with them. Or perhaps you attributed a different motive to them than what really underlies their actions. One misconception about conflict, however, is that it always arises from misunderstandings. This isn’t the case, however. Robert Doolittle (1976) noted that “some of the most serious conflicts occur among individuals and groups who understand each other very well but who strongly disagree.”

The first four kinds of conflict may interact with each other over time, either reinforcing or weakening each other’s impact. They may also ebb and flow according to the topics and conditions a group confronts. Even if they’re dealt with well, however, further emotional and personal kinds of conflict can occur in a group. Relationship conflicts, also known as personality clashes, often involve people’s egos and sense of self-worth. These conflicts tend to be particularly difficult to cope with since they frequently aren’t admitted for what they are. Many times, they arise in a struggle for superiority or status.

A Model of the Conflict Process

The most accepted model of the conflict process was developed by Kenneth Thomas (1976). This model consists of four stages: (1) frustration, (2) conceptualization, (3) behavior, and (4) outcome.

Stage 1: Frustration: As we have seen, conflict situations originate when an individual or group feels frustration in the pursuit of important goals. This frustration may be caused by a wide variety of factors, including disagreement over performance goals, failure to get a promotion or pay raise, a fight over scarce economic resources, new rules or policies, and so forth. In fact, conflict can be traced to frustration over almost anything a group or individual cares about.

Stage 2: Conceptualization: In stage 2, the conceptualization stage of the model, parties to the conflict attempt to understand the nature of the problem, what they themselves want as a resolution, what they think their opponents want as a resolution, and various strategies they feel each side may employ in resolving the conflict. This stage is really the problem-solving and strategy phase. For instance, when management and union negotiate a labor contract, both sides attempt to decide what is most important and what can be bargained away in exchange for these priority needs.

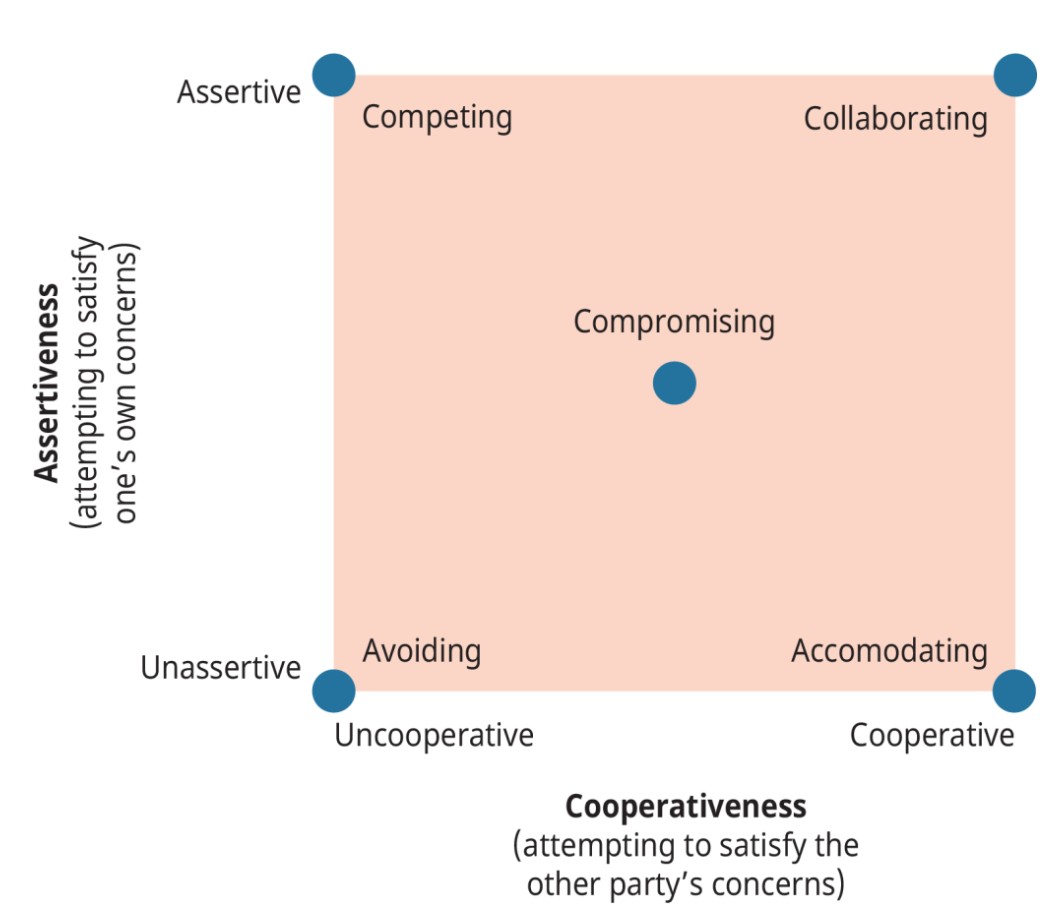

Stage 3: Behavior: The third stage in Thomas’s model is actual behavior. As a result of the conceptualization process, parties to a conflict attempt to implement their resolution mode by competing or accommodating in the hope of resolving problems. A major task here is determining how best to proceed strategically. That is, what tactics will the party use to attempt to resolve the conflict? Thomas has identified five modes for conflict resolution: (1) competing, (2) collaborating, (3) compromising, (4) avoiding, and (5) accommodating.

Click on each mode of conflict resolution to read more about the appropriate situations:

Competing

- When quick, decisive action is vital—e.g., emergencies

- On important issues where unpopular actions need implementing—e.g., cost-cutting, enforcing unpopular rules, discipline

- On issues vital to company welfare when you know you’re right

- Against people who take advantage of noncompetitive behavior

Collaborating

- When trying to find an integrative solution when both sets of concerns are too important to be compromised

- When your objective is to learn

- When merging insights from people with different perspectives

- When gaining commitment by incorporating concerns into a consensus

- When working through feelings that have interfered with a relationship

Compromising

- When goals are important but not worth the effort or potential disruption of more assertive modes

- When opponents with equal power are committed to mutually exclusive goals

- When attempting to achieve temporary settlements to complex issues

- When arriving at expedient solutions under time pressure

- As a backup when collaboration or competition is unsuccessful

Avoiding

- When an issue is trivial, or when more important issues are pressing

- When you perceive no chance of satisfying your concerns

- When potential disruption outweighs the benefits of resolution

- When letting people cool down and regain perspective

- When gathering information supersedes the immediate decision

- When others can resolve the conflict more effectively

- When issues seem tangential or symptomatic of other issues

Accommodating

- When you find you are wrong—to allow a better position to be heard, to learn, and to show your reasonableness

- When issues are more important to others than yourself—to satisfy others and maintain cooperation

- When building social credits for later issues

- When minimizing loss when you are outmatched and losing

- When harmony and stability are especially important

- When allowing subordinates to develop by learning from mistakes

When allowing subordinates to develop by learning from mistakes.

The choice of an appropriate conflict resolution mode depends to a great extent on the situation and the goals of the party. According to this model, each party must decide the extent to which it is interested in satisfying its own concerns—called assertiveness—and the extent to which it is interested in helping satisfy the opponent’s concerns—called cooperativeness. Assertiveness can range from assertive to unassertive on one continuum, and cooperativeness can range from uncooperative to cooperative on the other continuum.

Once the parties have determined their desired balance between the two competing concerns—either consciously or unconsciously—the resolution strategy emerges. For example, if a union negotiator feels confident she can win on an issue that is of primary concern to union members (e.g., wages), a direct competition mode may be chosen. On the other hand, when the union is indifferent to an issue or when it actually supports management’s concerns (e.g., plant safety), we would expect an accommodating or collaborating mode (on the right-hand side of the figure).

What is interesting in this process is the assumptions people make about their own modes compared to their opponents’. For example, in one study of executives, it was found that the executives typically described themselves as using collaboration or compromise to resolve conflict, whereas these same executives typically described their opponents as using a competitive mode almost exclusively (Thomas & Pondy, 1967). In other words, the executives underestimated their opponents’ concerns as uncompromising. Simultaneously, the executives had flattering portraits of their own willingness to satisfy both sides in a dispute.

Stage 4: Outcome. Finally, as a result of efforts to resolve the conflict, both sides determine the extent to which a satisfactory resolution or outcome has been achieved. Where one party to the conflict does not feel satisfied or feels only partially satisfied, the seeds of discontent are sown for a later conflict, as shown in the preceding figure. One unresolved conflict episode can easily set the stage for a second episode. Action aimed at achieving quick and satisfactory resolution is vital; failure to initiate such action leaves the possibility (more accurately, the probability) that new conflicts will soon emerge.

There are many steps and actions that group members can do to reduce or actually solve dysfunctional conflict when it occurs. These generally fall into two categories: actions directed at conflict prevention and actions directed at conflict reduction.

Strategies for Conflict Prevention

We shall start by examining conflict prevention techniques because preventing conflict is often easier than reducing it once it begins.

Video: Addressing Conflict with Care

Watch this video “Addressing Conflict with Care” where Simon Sinek discusses workplace negativity and conflict:

Click on each heading to read more about ways to prevent conflict:

Emphasizing group goals and effectiveness

Focusing on group goals and objectives should prevent goal conflict. If larger goals are emphasized, group members are more likely to see the big picture and work together to achieve corporate goals.

Providing stable, well-structured tasks

When work activities are clearly defined, understood, and accepted, conflict should be less likely to occur. Conflict is most likely to occur when task uncertainty is high; specifying or structuring roles and tasks minimizes ambiguity.

Facilitating dialogue

Misperception of the abilities, goals, and motivations of others often leads to conflict, so efforts to increase the dialogue among group members and to share information should help eliminate conflict. As group members come to know more about one another, suspicions often diminish, and greater intergroup teamwork becomes possible.

Avoiding win-lose situations

If win-lose situations are avoided, less potential for conflict exists.

Where dysfunctional conflict already exists, something must be done, and you may pursue one of at least two general approaches: you can try to change attitudes, or you can try to behaviors. If you change behavior, open conflict is often reduced, but group members may still dislike one another; the conflict simply becomes less visible.

Changing attitudes, on the other hand, often leads to fundamental changes in the ways that groups get along. However, it also takes considerably longer to accomplish than behavior change because it requires a fundamental change in social perceptions.

Conclusion

Conflict is an inevitable part of professional life, but when managed effectively, it can lead to growth, innovation, and stronger relationships. Understanding the nature of conflict—whether it stems from differences in values, goals, or communication styles—empowers individuals and teams to address challenges constructively. Ultimately, mastering conflict and negotiation skills is essential for maintaining a respectful, productive workplace and fostering long-term success in any business environment.

How to cite this chapter:

Piercy, C. (2021). Chapter 16: Conflict and Negotiation. In Pouska, B. (Ed.), Business Professionalism. New Mexico Open Educational Resources Consortium Pressbooks. https://nmoer.pressbooks.pub/businessprofessionalism/

Licenses and Attributions

References

Bach, G., & Wyden, P. (1968). The intimacy enemy. Avon.

Brown, D. L. (1986). Managing conflict at organizational interfaces. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc.

Coser, L. (1956). The functions of social conflict. Free Press.

Doolittle, R. J. (1976). Orientations to communication and conflict. Science Research Associates.

Hocker, J. L., & Wilmot, W. W. (2001). Interpersonal conflict (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Kelly, M. S. (2006). Communication @ work: Ethical, effective, and expressive communication in the workplace. Pearson.

Neilsen, E. H. (1972). Understanding and managing conflict. In J. Lorsch & P. Lawrence (Eds.), Managing group and intergroup relations. Irwin.

Rokeach, M. (1979). Understanding human values: Individual and societal. The Free Press.

Sinek, S. (2024). Addressing conflict with care: Simon Sinek’s approach to workplace negativity [Video].

Thomas, K. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational behavior. Wiley.

Thomas, K., & Pondy, L. (1967). Toward an intent model of conflict management among principal parties. Human Relations, 30, 1089–1102.

Authors and Attribution

This remix was created by Dr. Jasmine Linabary at Emporia State University. This chapter is also available in her book Small Group Communication: Forming and Sustaining Teams.

The sections “The Positive and Negative Sides of Conflict,” “A Model of the Conflict Process,” and “Managing Conflict in Groups” are adapted from Black, J. S., & Bright, D. S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/. The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY 4.0).

The sections “Definitions of Conflict,” “Types of Conflict,” and “Recognizing Emotion” are adapted from Managing Conflict in An Introduction to Group Communication. This content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

Original Chapter Source

Original chapter source: Adapted from Problem Solving in Teams and Groups by Cameron W. Piercy, PhD.