Chapter 23: Cooperation

Chapter Learning Objectives

- 23.1 Define cooperation in a professional context and explain its role in fostering teamwork, productivity, and a positive workplace culture. (SLO 1, 2, 4)

- 23.2 Identify behaviors that promote cooperative work environments, such as active listening, empathy, and shared responsibility. (SLO 1, 2, 4, 5)

- 23.3 Analyze the impact of cooperation on conflict resolution, decision-making, and achieving common goals within teams and organizations. (SLO 1, 2, 4, 5)

- 23.4 Evaluate personal and team performance in terms of cooperative behavior and identify areas for improvement in collaboration skills. (SLO 1, 2, 4, 5)

People cooperate with others throughout their life. Whether on the playground with friends, at home with family, or at work with colleagues, cooperation is a natural instinct. Humans’ closest evolutionary relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, maintain long-term cooperative relationships as well, sharing resources and caring for each other’s young. Ancient animal remains found near early human settlements suggest that our ancestors hunted in cooperative groups. Cooperation, it seems, is embedded in our evolutionary heritage.

Yet, cooperation can also be difficult to achieve; there are often breakdowns in people’s ability to work effectively in teams, or in their willingness to collaborate with others. Even with issues that can only be solved through large-scale cooperation, such as climate change and world hunger, people can have difficulties joining forces with others to take collective action.

Psychologists have identified numerous individual and situational factors that influence the effectiveness of cooperation across many areas of life. From the trust that people place in others to the lines they draw between “us” and “them,” many different processes shape cooperation. This chapter will explore these individual, situational, and cultural influences on cooperation.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Imagine that you are a participant in a social experiment. As you sit down, you are told that you will be playing a game with another person in a separate room. The other participant is also part of the experiment but the two of you will never meet. In the experiment, there is the possibility that you will be awarded some money.

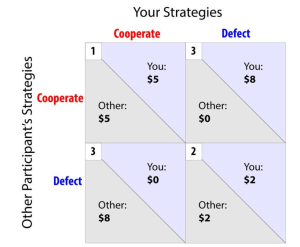

Both you and your unknown partner are required to make a choice: either choose to “cooperate,” maximizing your combined reward, or “defect,” (not cooperate) and thereby maximize your individual reward. The choice you make, along with that of the other participant, will result in one of three unique outcomes to this task.

- If you and your partner both cooperate (1), you will each receive $5.

- If you and your partner both defect (2), you will each receive $2.

- However, if one partner defects and the other partner cooperates (3), the defector will receive $8, while the cooperator will receive nothing.

Remember, you and your partner cannot discuss your strategy. Which would you choose? Striking out on your own promises big rewards but you could also lose everything. Cooperating, on the other hand, offers the best benefit for the most people but requires a high level of trust.

Video: The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Watch this animated video to help explain The Prisoner’s Dilemma more:

This scenario, in which two people independently choose between cooperation and defection, is known as the prisoner’s dilemma. It gets its name from the situation in which two prisoners who have committed a crime are given the opportunity to either (A) both confess their crime (and get a moderate sentence), (B) rat out their accomplice (and get a lesser sentence), or (C) both remain silent (and avoid punishment altogether).

Psychologists use various forms of the prisoner’s dilemma scenario to study self-interest and cooperation. Whether framed as a monetary game or a prison game, the prisoner’s dilemma illuminates a conflict at the core of many decisions to cooperate it pits the motivation to maximize personal reward against the motivation to maximize gains for the group (you and your partner combined).

For someone trying to maximize his or her own personal reward, the most “rational” choice is to defect (not cooperate), because defecting always results in a larger personal reward, regardless of the partner’s choice. However, when the two participants view their partnership as a joint effort (such as a friendly relationship), cooperating is the best strategy of all, since it provides the largest combined sum of money ($10—which they share), as opposed to partial cooperation ($8), or mutual defection ($4). In other words, although defecting represents the “best” choice from an individual perspective, it is also the worst choice to make for the group as a whole.

This divide between personal and collective interests is a key obstacle that prevents people from cooperating. Think back to our earlier definition of cooperation is when multiple partners work together toward a common goal that will benefit everyone. As is frequent in these types of scenarios, even though cooperation may benefit the whole group, individuals are often able to earn even larger, personal rewards by defecting—as demonstrated in the prisoner’s dilemma example above.

You can see a small, real-world example of the prisoner’s dilemma phenomenon at live music concerts. At venues with seating, many audience members will choose to stand, hoping to get a better view of the musicians onstage. As a result, the people sitting directly behind those now-standing people are also forced to stand to see the action onstage. This creates a chain reaction in which the entire audience now has to stand, just to see over the heads of the crowd in front of them. While choosing to stand may improve one’s own concert experience, it creates a literal barrier for the rest of the audience, hurting the overall experience of the group.

Simple models of rational self-interest predict 100% defection in cooperative tasks. That is, if people were only interested in benefiting themselves, we would always expect to see selfish behavior. Instead, there is a surprising tendency to cooperate in the prisoner’s dilemma and similar tasks (Batson & Moran, 1999; Oosterbeek et al., 2004).

Given the clear benefits to defect, why then do some people choose to cooperate, whereas others choose to defect?

Social Value Orientation

One key factor related to individual differences in cooperation is the extent to which people value not only their own outcomes, but also the outcomes of others. Social value orientation (SVO) describes people’s preferences when dividing important resources between themselves and others (Messick & McClintock, 1968).

A person might, for example, generally be competitive with others, or cooperative, or self-sacrificing. People with different social values differ in the importance they place on their own positive outcomes relative to the outcomes of others. For example, you might give your friend gas money because she drives you to school, even though that means you will have less spending money for the weekend. In this example, you are demonstrating a cooperative orientation.

People generally fall into one of three categories of SVO: cooperative, individualistic, or competitive. While most people want to bring about positive outcomes for all (cooperative orientation), certain types of people are less concerned about the outcomes of others (individualistic), or even seek to undermine others in order to get ahead (competitive orientation).

Empathic Ability

Empathy is the ability to feel and understand another’s emotional experience. When we empathize with someone else, we take on that person’s perspective, imagining the world from his or her point of view and vicariously experiencing his or her emotions (Davis, 1994; Goetz et al., 2010). Research has shown that when people empathize with their partner, they act with greater cooperation and overall altruism—the desire to help the partner, even at a potential cost to the self. People who can experience and understand the emotions of others are better able to work with others in groups, earning higher job performance ratings on average from their supervisors, even after adjusting for different types of work and other aspects of personality (Côté & Miners, 2006).

When empathizing with a person in distress, the natural desire to help is often expressed as a desire to cooperate. Evidence of the link between empathy and cooperation has even been found in studies of preschool children (Marcus et al., 1979). From a very early age, emotional understanding can foster cooperation.

Although empathizing with a partner can lead to more cooperation between two people, it can also undercut cooperation within larger groups. In groups, empathizing with a single person can lead people to abandon broader cooperation in favor of helping only the target individual.

Though empathy can create strong cooperative bonds between individuals, it can sometimes lead to actions that, despite being well-intentioned, end up undermining the group’s best interests.

Communication and Commitment

Open communication between people is one of the best ways to promote cooperation. This is because communication provides an opportunity to size up the trustworthiness of others. It also affords us a chance to prove our own trustworthiness, by verbally committing to cooperate with others. Since cooperation requires people to enter a state of vulnerability and trust with partners, we are very sensitive to the social cues and interactions of potential partners before deciding to cooperate with them.

Trust

When it comes to cooperation, trust is key. Working with others toward a common goal requires a level of faith that our partners will repay our hard work and generosity and not take advantage of us for their own selfish gains. Social trust, or the belief that another person’s actions will be beneficial to one’s own interests (Kramer, 1999), enables people to work together as a single unit, pooling their resources to accomplish more than they could individually. Trusting others, however, depends on their actions and reputation.

One common example of the difficulties in trusting others that you might recognize from being a student occurs when you are assigned a group project. Many students dislike group projects because they worry about social loafing—the way that one person expends less effort but still benefits from the efforts of the group.

Imagine, for example, that you and five other students are assigned to work together on a difficult class project. At first, you and your group members split the work up evenly. As the project continues, however, you notice that one member of your team isn’t doing his “fair share.” He fails to show up to meetings, his work is sloppy, and he seems generally uninterested in contributing to the project. After a while, you might begin to suspect that this student is trying to get by with minimal effort, perhaps assuming others will pick up the slack. Your group now faces a difficult choice: either join the slacker and abandon all work on the project, causing it to collapse, or keep cooperating and allow for the possibility that the uncooperative student may receive a decent grade for others’ work.

If this scenario sounds familiar to you, you’re not alone. Economists call this situation the free rider problem -when individuals benefit from the cooperation of others without contributing anything in return (Grossman & Hart, 1980). Although these sorts of actions may benefit the free rider in the short-term, free riding can have a negative impact on a person’s social reputation over time. In the above example, for instance, the “free riding” student may develop a reputation as lazy or untrustworthy, leading others to be less willing to work with him or her in the future.

Indeed, research has shown that a poor reputation for cooperation can serve as a warning sign for others not to cooperate with the person in disrepute. When someone is seen being consistently uncooperative, other people have no incentive to trust him/her, resulting in a collapse of cooperation.

On the other hand, people are more likely to cooperate with others who have a good reputation for cooperation and are therefore deemed trustworthy. Individuals seen cooperating with others were afforded a reputational advantage, earning them more partners willing to cooperate and a larger overall monetary reward.

Group Identification

Another factor that can impact cooperation is a person’s social identity, or the extent to which he or she identifies as a member of a particular social group (Tajfel & Turner, 1979/1986). People can identify with groups of all shapes and sizes: a group might be relatively small, such as a local high school class, or very large, such as a national citizenship or a political party. While these groups are often bound together by shared goals and values, they can also form according to seemingly arbitrary qualities, such as musical taste, hometown, or even completely randomized assignment, such as a coin toss. When members of a group place a high value on their group membership, their identity (the way they view themselves) can be shaped in part by the goals and values of that group.

Researchers have found that groups interacting with other groups are more competitive and less cooperative than individuals interacting with other individuals, a phenomenon known as interindividual-intergroup discontinuity (Schopler &; Insko, 1999; Wildschut et al. 2003). Such problems with trust and cooperation are largely due to people’s general reluctance to cooperate with members of an outgroup, or those outside the boundaries of one’s own social group. Outgroups do not have to be explicit rivals for this effect to take place. Though a strong group identity can bind individuals within the group together, it can also drive divisions between different groups, reducing overall trust and cooperation on a larger scope.

Under the right circumstances, however, even rival groups can be turned into cooperative partners in the presence of superordinate goals. Researchers conclude that when conflicting groups share a superordinate goal, they are capable of shifting their attitudes and bridging group differences to become cooperative partners.

Culture

Culture can have a powerful effect on people’s beliefs about and ways they interact with others. Might culture also affect a person’s tendency toward cooperation? Very few of us in industrialized societies live in houses we build ourselves, wear clothes we make ourselves, or eat food we grow ourselves. Instead, we depend on others to provide specialized resources and products, such as food, clothing, and shelter that are essential to our survival. While living in an industrialized society might not require us to hunt in groups, we still depend on others to supply the resources we need to survive.

Conclusion

Cooperation is essential for groups and teams to be effective in their work. Even with the best of intentions, psychology, culture and personal identifications can create challenges for a group.

How to cite this chapter:

Piercy, C. (2021). Chapter 23: Cooperation. In Pouska, B. (Ed.), Business Professionalism. New Mexico Open Educational Resources Consortium Pressbooks. https://nmoer.pressbooks.pub/businessprofessionalism/

Licenses and Attributions

References

Allport, F. H. (1924). Social psychology. Houghton Mifflin.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. (2001). Empathy-induced altruism in a prisoner’s dilemma II: What if the target of empathy has defected? European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(1), 25–36.

Batson, C. D., & Moran, T. (1999). Empathy-induced altruism in a prisoner’s dilemma. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(7), 909–924.

Batson, C. D., Batson, J. G., Todd, R. M., Brummett, B. H., Shaw, L. L., & Aldeguer, C. M. (1995). Empathy and the collective good: Caring for one of the others in a social dilemma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 619.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Bigler, R. S., Brown, C. S., & Markell, M. (2001). When groups are not created equal: Effects of group status on the formation of intergroup attitudes in children. Child Development, 72(4), 1151–1162.

Blascovich, J., Mendes, W. B., Hunter, S. B., & Salomon, K. (1999). Social “facilitation” as challenge and threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 68–77.

Bond, C. F., Atoum, A. O., & VanLeeuwen, M. D. (1996). Social impairment of complex learning in the wake of public embarrassment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 31–44.

Brewer, M. B., & Kramer, R. M. (1986). Choice behavior in social dilemmas: Effects of social identity, group size, and decision framing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(3), 543–549.

Buote, V. M., Pancer, S. M., Pratt, M. W., Adams, G., Birnie-Lefcovitch, S., Polivy, J., & Wintre, M. G. (2007). The importance of friends: Friendship and adjustment among first-year university students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(6), 665–689.

Chaudhuri, A., Sopher, B., & Strand, P. (2002). Cooperation in social dilemmas, trust and reciprocity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23(2), 231–249.

Côté, S., & Miners, C. T. (2006). Emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence, and job performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(1), 1–28.

Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. (1990). Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 60–67.

Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630.

Cropanzano, R., & Byrne, Z. S. (2000). Workplace justice and the dilemma of organizational citizenship. In M. Van Vugt, M. Snyder, T. Tyler, & A. Biel (Eds.), Cooperation in modern society: Promoting the welfare of communities, states, and organizations (pp. 142–161). Routledge.

Darwin, C. (1859/1963). The origin of species. Washington Square Press.

Dashiell, J. F. (1930). An experimental analysis of some group effects. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 25, 190–199.

Davis, M. H. (1994). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Westview Press.

Dawes, R. M., & Kagan, J. (1988). Rational choice in an uncertain world. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Dawes, R. M., McTavish, J., & Shaklee, H. (1977). Behavior, communication, and assumptions about other people’s behavior in a commons dilemma situation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(1), 1.

De Waal, F. B. M., & Lanting, F. (1997). Bonobo: The forgotten ape. University of California Press.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1980). Takeover bids, the free-rider problem, and the theory of the corporation. The Bell Journal of Economics, 11(1), 42–64.

Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., & McElreath, R. (2001). In search of homo economicus: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. The American Economic Review, 91(2), 73–78.

Insko, C. A., Kirchner, J. L., Pinter, B., Efaw, J., & Wildschut, T. (2005). Interindividual–intergroup discontinuity as a function of trust and categorization: The paradox of expected cooperation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(2), 365–385.

Insko, C. A., Pinkley, R. L., Hoyle, R. H., Dalton, B., Hong, G., Slim, R. M., … & Thibaut, J. (1987). Individual versus group discontinuity: The role of intergroup contact. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 23(3), 250–267.

Keltner, D., Kogan, A., Piff, P. K., & Saturn, S. R. (2014). The sociocultural appraisals, values, and emotions (SAVE) framework of prosociality: Core processes from gene to meme. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 425–460.

Kerr, N. L., & Kaufman-Gilliland, C. M. (1994). Communication, commitment, and cooperation in social dilemmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(3), 513–529.

Kerr, N. L., Garst, J., Lewandowski, D. A., & Harris, S. E. (1997). That still, small voice: Commitment to cooperate as an internalized versus a social norm. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(12), 1300–1311.

Klandermans, B. (2002). How group identification helps to overcome the dilemma of collective action. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 887–900.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 569–598.

Kramer, R. M., McClintock, C. G., & Messick, D. M. (1986). Social values and cooperative response to a simulated resource conservation crisis. Journal of Personality, 54(3), 576–582.

Langergraber, K. E., Mitani, J. C., & Vigilant, L. (2007). The limited impact of kinship on cooperation in wild chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(19), 7786–7790.

Locksley, A., Ortiz, V., & Hepburn, C. (1980). Social categorization and discriminatory behavior: Extinguishing the minimal intergroup discrimination effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 773–783.

Marcus, R. F., Telleen, S., & Roke, E. J. (1979). Relation between cooperation and empathy in young children. Developmental Psychology, 15(3), 346.

McClintock, C. G., & Allison, S. T. (1989). Social value orientation and helping behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19(4), 353–362.

Messick, D. M., & McClintock, C. G. (1968). Motivational bases of choice in experimental games. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4(1), 1–25.

Milinski, M., Semmann, D., Bakker, T. C., & Krambeck, H. J. (2001). Cooperation through indirect reciprocity: Image scoring or standing strategy? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 268(1484), 2495–2501.

Mithen, S. (1999). The prehistory of the mind: The cognitive origins of art, religion and science. Thames & Hudson Publishers.

One Minute Economics. (2016). The prisoner’s dilemma explained in one minute [Video]. YouTube. (Licensed under Standard YouTube License – All Rights Reserved.)

Oosterbeek, H., Sloof, R., & Van De Kuilen, G. (2004). Cultural differences in ultimatum game experiments: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Experimental Economics, 7(2), 171–188.

Parks, C. D., Henager, R. F., & Scamahorn, S. D. (1996). Trust and reactions to messages of intent in social dilemmas. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 40(1), 134–151.

Pruitt, D. G., & Kimmel, M. J. (1977). Twenty years of experimental gaming: Critique, synthesis, and suggestions for the future. Annual Review of Psychology, 28, 363–392.

Roch, S. G., & Samuelson, C. D. (1997). Effects of environmental uncertainty and social value orientation in resource dilemmas. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 70(3), 221–235.

Schopler, J., & Insko, C. A. (1999). The reduction of the interindividual–intergroup discontinuity effect: The role of future consequences. In M. Foddy, M. Smithson, S. Schneider, & M. Hogg (Eds.), Resolving social dilemmas: Dynamic, structural, and intergroup aspects (pp. 281–294). Psychology Press.

Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J., Hood, W. R., & Sherif, C. W. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment. University Book Exchange.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

Van Lange, P. A., Bekkers, R., Schuyt, T. N., & Van Vugt, M. (2007). From games to giving: Social value orientation predicts donations to noble causes. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(4), 375–384.

Van Vugt, M., Biel, A., Snyder, M., & Tyler, T. (2000). Perspectives on cooperation in modern society: Helping the self, the community, and society. In M. Van Vugt, M. Snyder, T. Tyler, & A. Biel (Eds.), Cooperation in modern society: Promoting the welfare of communities, states, and organizations (pp. 3–24). Routledge.

Van Vugt, M., & Hart, C. M. (2004). Social identity as social glue: The origins of group loyalty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(4), 585–598.

Van Vugt, M., Meertens, R. M., & Van Lange, P. A. (1995). Car versus public transportation? The role of social value orientations in a real-life social dilemma. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 258–278.

Van Vugt, M., Van Lange, P. A., & Meertens, R. M. (1996). Commuting by car or public transportation? A social dilemma analysis of travel mode judgements. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(3), 373–395.

Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Helping and cooperation at 14 months of age. Infancy, 11(3), 271–294.

Warneken, F., Chen, F., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Cooperative activities in young children and chimpanzees. Child Development, 77(3), 640–663.

Wedekind, C., & Milinski, M. (2000). Cooperation through image scoring in humans. Science, 288(5467), 850–852.

Wildschut, T., Pinter, B., Vevea, J. L., Insko, C. A., & Schopler, J. (2003). Beyond the group mind: A quantitative review of the interindividual–intergroup discontinuity effect. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 698–722.

Original Chapter Source

Original chapter source: Adapted from Problem Solving in Teams and Groups by Cameron W. Piercy, PhD.

Additional content: Portions adapted from The Noba Project by Jake P. Moskowitz and Paul K. Piff. (Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.)