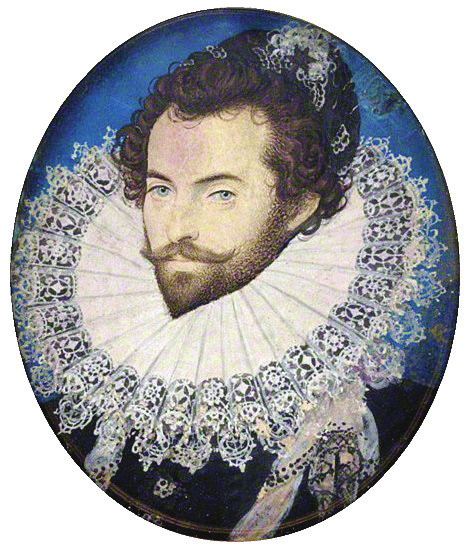

28 2.9-2.9.7 Sir Walter Raleigh

2.9 SIR WALTER RALEIGH

(1552-1618)

A soldier, explorer, scholar, and courtier, Walter Raleigh fought on the side of the French Protestants, the Huguenots, possibly in the Battle of Jarnac during the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598). He also participated in the massacre at Smerwick, brutally suppressing Irish rebels and slaughtering papal troops. He was tutored by the vicar John Ford, enrolled at Oriel College, Oxford University, and studied at one of the Inns of Court, the Middle Temple. Family connections probably won him a place in Elizabeth I’s court, as Esquire of the Body Extraordinary.

His own charisma won him many favors from Elizabeth I, including a license to tax vintners for retailing wine in England, Durham House, a knighthood, the title of Lord and Governor of Virginia, thousands of acres of land in Ireland, and an appointment as Captain of the Guard. He also was elected to Parliament and appointed Lord Warden of the Stanneries, Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall, and Vice-Admiral of Cornwall and Devon. He used his wealth to fund voyages to Roanoke Island in hopes of settling a colony there and instead mysteriously losing the colonists. Although he did not introduce the potato and tobacco in Virginia, as he is often credited for doing, he did popularize smoking at Court.

He lost Elizabeth I’s favor when he secretly married one of her maids of honor, Elizabeth Throckmorton (1565-1647), who as a royal attendant could only marry with the Queen’s permission. She briefly imprisoned them both in the Tower of London. He soon continued his colonizing efforts by exploring Guiana in South America and futilely searching for El Dorado, the so-called Lost City of Gold.

Much of what he gained from Elizabeth Raleigh lost when she was succeeded by James I. Raleigh was implicated in two conspiracies against James I, the Bye and the Main Plots, for which he was condemned of treason and imprisoned for over ten years in the Tower. Upon his release, he courted James I’s favor by again voyaging to Guiana in search of gold. He failed in this intention and, worse, disobeyed James I’s injunction not to violate Spanish rights when his men destroyed the village of Santo Tome de Guyana. For endangering England’s peace with Spain, Raleigh was beheaded.

Raleigh’s writing records the fierce, cynical, plausible voice of the man and his many exploits. His love poetry wooed and “won” Elizabeth I; his book The during his imprisonment. His pastoral poetry both repeats and renews that classical genre, with his reply to Marlowe’s Passionate Shepherd gaining much attention. His poem The Lie, with its all-encompassing attacks on the Court, Church, Men of High Condition, faith, wit, and learning, provoked several answering, often defensive, poems. His travelogue, like many that follow, blends fiction with “fact.” And his History recovers the past in an attempt to shape the future.

2.9.1 “Farewell, False Love”

(1588)

Farewell, false love, the oracle of lies,

A mortal foe and enemy to rest,

An envious boy, from whom all cares arise,

A bastard vile, a beast with rage possessed,

A way of error, a temple full of treason,

In all effects contrary unto reason.

A poisoned serpent covered all with flowers,

Mother of sighs, and murderer of repose,

A sea of sorrows whence are drawn such showers

As moisture lend to every grief that grows;

A school of guile, a net of deep deceit,

A gilded hook that holds a poisoned bait.

A fortress foiled, which reason did defend,

A siren song, a fever of the mind,

A maze wherein affection finds no end,

A raging cloud that runs before the wind,

A substance like the shadow of the sun,

A goal of grief for which the wisest run.

A quenchless fire, a nurse of trembling fear,

A path that leads to peril and mishap,

A true retreat of sorrow and despair,

An idle boy that sleeps in pleasure’s lap,

A deep mistrust of that which certain seems,

A hope of that which reason doubtful deems.

Sith then thy trains my younger years betrayed,

And for my faith ingratitude I find;

And sith repentance hath my wrongs bewrayed, Dead is the root whence all these fancies grew.

2.9.2 “If Cynthia Be a Queen, a Princess, and Supreme”

(1604/1618?)

If Cynthia be a queen, a princess, and supreme,

Keep these among the rest, or say it was a dream,

For those that like, expound, and those that loathe express Meanings according as their minds are moved more or less; For writing what thou art, or showing what thou were, Adds to the one disdain, to the other but despair,

Thy mind of neither needs, in both seeing it exceeds.

2.9.3 “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd”

(1600)

If all the world and love were young,

And truth in every Shepherd’s tongue,

These pretty pleasures might me move,

To live with thee, and be thy love.

Time drives the flocks from field to fold,

When Rivers rage and Rocks grow cold,

And Philomel becometh dumb,

The rest complains of cares to come.

The flowers do fade, and wanton fields,

To wayward winter reckoning yields,

A honey tongue, a heart of gall,

Is fancy’s spring, but sorrow’s fall.

Thy gowns, thy shoes, thy beds of Roses,

Thy cap, thy kirtle, and thy posies

Soon break, soon wither, soon forgotten:

In folly ripe, in reason rotten.

Thy belt of straw and Ivy buds,

The Coral clasps and amber studs,

All these in me no means can move

To come to thee and be thy love.

Then these delights my mind might move

To live with thee, and be thy love.

2.9.4 “The Lie”

(1608)

Go, soul, the body’s guest,

Upon a thankless errand;

Fear not to touch the best;

The truth shall be thy warrant.

Go, since I needs must die,

And give the world the lie.

Say to the court, it glows

And shines like rotten wood;

Say to the church, it shows

What’s good, and doth no good.

If church and court reply,

Then give them both the lie.

Tell potentates, they live

Acting by others’ action;

Not loved unless they give,

Not strong but by a faction.

If potentates reply,

Give potentates the lie.

Tell men of high condition,

That manage the estate,

Their purpose is ambition,

Their practice only hate.

And if they once reply,

Then give them all the lie.

Tell them that brave it most,

They beg for more by spending,

Who, in their greatest cost,

Seek nothing but commending.

And if they make reply,

Then give them all the lie.

Tell time it is but motion;

Tell flesh it is but dust.

And wish them not reply,

For thou must give the lie.

Tell age it daily wasteth;

Tell honor how it alters;

Tell beauty how she blasteth;

Tell favor how it falters.

And as they shall reply,

Give every one the lie.

Tell wit how much it wrangles

In tickle points of niceness;

Tell wisdom she entangles

Herself in overwiseness.

And when they do reply,

Straight give them both the lie.

Tell physic of her boldness;

Tell skill it is pretension;

Tell charity of coldness;

Tell law it is contention.

And as they do reply,

So give them still the lie.

Tell fortune of her blindness;

Tell nature of decay;

Tell friendship of unkindness;

Tell justice of delay.

And if they will reply,

Then give them all the lie.

Tell arts they have no soundness,

But vary by esteeming;

Tell schools they want profoundness,

And stand too much on seeming.

If arts and schools reply,

Give arts and schools the lie.

Tell manhood shakes off pity;

Tell virtue least preferreth.

And if they do reply,

Spare not to give the lie.

So when thou hast, as I

Commanded thee, done blabbing—

Although to give the lie

Deserves no less than stabbing—

Stab at thee he that will,

No stab the soul can kill.

2.9.5 “Nature, That Washed Her Hands in Milk”

(Published in 1902)

Nature, that washed her hands in milk,

And had forgot to dry them,

Instead of earth took snow and silk,

At love’s request to try them,

If she a mistress could compose

To please love’s fancy out of those.

Her eyes he would should be of light,

A violet breath, and lips of jelly;

Her hair not black, nor overbright,

And of the softest down her belly;

As for her inside he’d have it

Only of wantonness and wit.

At love’s entreaty such a one

Nature made, but with her beauty

She hath framed a heart of stone;

So as love, by ill destiny,

Must die for her whom nature gave him,

Because her darling would not save him.

But time (which nature doth despise,

And rudely gives her love the lie,

Makes hope a fool, and sorrow wise)

His hands do neither wash nor dry;

The light, the belly, lips, and breath,

He dims, discolors, and destroys;

With those he feeds but fills not death,

Which sometimes were the food of joys.

Yea, time doth dull each lively wit,

And dries all wantonness with it.

Oh, cruel time! which takes in trust

Our youth, our joys, and all we have,

And pays us but with age and dust;

Who in the dark and silent grave

When we have wandered all our ways

Shuts up the story of our days.

2.9.6 From The Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana

(1599)

The next morning we also left the port, and sailed westward up to the river, to view the famous river called Caroli, as well because it was marvelous of itself, as also for that I understood it led to the strongest nations of all the frontiers, that were enemies to the Epuremei, which are subjects to Inga, emperor of Guiana and Manoa. And that night we anchored at another island called Caiama, of some five or six miles in length; and the next day arrived at the mouth of Caroli. When we were short of it as low or further down as the port of Morequito, we heard the great roar and fall of the river. But when we came to enter with our barge and wherries, thinking to have gone up some forty miles to the nations of the Cassipagotos, we were not able with a barge of eight oars to row one stone’s cast in an hour; and yet the river is as broad as the Thames at Woolwich, and we tried both sides, and the middle, and every part of the river. So as we encamped upon the banks adjoining, and sent off our Orenoquepone which came with us from Morequito to give knowledge to the nations upon the river of our being there, and that we desired to see the lords of Canuria, which dwelt within the province upon that river, making them know that we were enemies to the Spaniards; for it was on this river side that Morequito slew the friar, and those nine Spaniards which came from Manoa, the city of Inga, and took from them 14,000 pesos of gold. So as the next day there came down a lord or cacique, called Wanuretona, with many people with him, and brought all store of provisions to entertain us, as the rest had done. And as I had before made my coming known to Topiawari, so did I acquaint this cacique therewith, and how I was sent by her Majesty for the purpose aforesaid, to the Epuremei, which abound in gold. And by this Wanuretona I had knowledge that on the head of this river were three mighty nations, which were seated on a great lake, from whence this river descended, and were called Cassipagotos, Eparegotos, and Arawagotos; and that all those either against the Spaniards or the Epuremei would join with us, and that if we entered the land over the mountains of Curaa we should satisfy ourselves with gold and all other good things. He told us farther of a nation called Iwarawaqueri, before spoken of, that held daily war with the Epuremei that inhabited Macureguarai, and first civil town of Guiana, of the subjects of Inga, the emperor.

Upon this river one Captain George, that I took with Berreo, told me that there was a great silver mine, and that it was near the banks of the said river. But by this time as well Orenoque, Caroli, as all the rest of the rivers were risen four or five feet in height, so as it was not possible by the strength of any men, or with any boat whatsoever, to row into the river against the stream. I therefore sent Captain Thyn, Captain Greenvile, my nephew John Gilbert, my cousin Butshead Gorges, Captain Clarke, and some thirty shot more to coast the river by land, and to go to a town some twenty miles over the valley called Amnatapoi; and they found guides there to go farther towards the mountain foot to another great town called Capurepana, belonging to a cacique called Haharacoa, that was a nephew to old Topiawari, king of Aromaia, our chiefest friend, because this town and province of Capurepana adjoined to Macureguarai, which was a frontier town of the empire. And the meanwhile myself with Captain Gifford, Captain Caulfield, Edward Hancock, and some half-a-dozen shot marched overland to view the strange overfalls of the river of Caroli, which roared so far off; and also to see the plains adjoining, and the rest of the province of Canuri. I sent also Captain Whiddon, William Connock, and some eight shot with them, to see if they could find any mineral stone alongst the river’s side. When we were come to the tops of the first hills of the plains adjoining to the river, we beheld that wonderful breach of waters which ran down Caroli; and might from that mountain see the river how it ran in three parts, above twenty miles off, and there appeared some ten or twelve overfalls in sight, every one as high over the other as a church tower, which fell with that fury, that the rebound of water made it seem as if it had been all covered over with a great shower of rain; and in some places we took it at the first for a smoke that had risen over some great town. For mine own part I was well persuaded from thence to have returned, being a very ill footman; but the rest were all so desirous to go near the said strange thunder of waters, as they drew me on by little and little, till we came into the next valley, where we might better discern the same. I never saw a more beautiful country, nor more lively prospects; hills so raised here and there over the valley; the river winding into divers branches; the plains adjoining without bush or stubble, all fair green grass; the ground of hard sand, easy to march on, either for horse or foot; the deer crossing in every path; the birds towards the evening easterly wind; and every stone that we stooped to take up promised either gold or silver by his complexion. Your Lordship shall see of many sorts, and I hope some of them cannot be bettered under the sun; and yet we had no means but with our daggers and fingers to tear them out here and there, the rocks being most hard of that mineral spar aforesaid, which is like a flint, and is altogether as hard or harder, and besides the veins lie a fathom or two deep in the rocks. But we wanted all things requisite save only our desires and good will to have performed more if it had pleased God. To be short, when both our companies returned, each of them brought also several sorts of stones that appeared very fair, but were such as they found loose on the ground, and were for the most part but coloured, and had not any gold fixed in them. Yet such as had no judgment or experience kept all that glistered, and would not be persuaded but it was rich because of the lustre; and brought of those, and of marcasite withal, from Trinidad, and have delivered of those stones to be tried in many places, and have thereby bred an opinion that all the rest is of the same. Yet some of these stones I shewed afterward to a Spaniard of the Caracas, who told me that it was El Madre del Oro, that is, the mother of gold, and that the mine was farther in the ground. . . .

For the rest, which myself have seen, I will promise these things that follow, which I know to be true. Those that are desirous to discover and to see many nations may be satisfied within this river, which bringeth forth so many arms and branches leading to several countries and provinces, above 2,000 miles east and west and 800 miles south and north, and of these the most either rich in gold or in other merchandises. The common soldier shall here fight for gold, and pay himself, instead of pence, with plates of half-a-foot broad, whereas he breaketh his bones in other wars for provant and penury. Those commanders and chieftains that shoot at honour and abundance shall find there more rich and beautiful cities, more temples adorned with golden images, more sepulchres filled with treasure, than either Cortes found in Mexico or Pizarro in Peru. And the shining glory of this conquest will eclipse all those so far-extended beams of the Spanish nation. There is no country which yieldeth more pleasure to the inhabitants, either for those common delights of hunting, hawking, fishing, fowling, and the rest, than Guiana doth; it hath so many plains, clear rivers, and abundance of pheasants, partridges, quails, rails, cranes, herons, and all other fowl; deer of all sorts, porks, hares, lions, tigers, leopards, and divers other sorts of beasts, either for chase or food. It hath a kind of beast called cama or anta, as big as an English beef, and in great plenty. To speak of the several sorts of every kind I fear would be troublesome to the reader, and therefore I will omit them, and conclude that both for health, good air, pleasure, and riches, I am resolved it cannot be equalled by any region either in the east or west. Moreover the country is so healthful, as of an hundred persons and more, which lay without shift most sluttishly, and were every day almost melted with heat in rowing and marching, and suddenly wet again with and bad, without either order or measure, and besides lodged in the open air every night, we lost not any one, nor had one ill-disposed to my knowledge; nor found any calentura or other of those pestilent diseases which dwell in all hot regions, and so near the equinoctial line. . . .

To conclude, Guiana is a country that hath yet her maidenhead, never sacked, turned, nor wrought; the face of the earth hath not been torn, nor the virtue and salt of the soil spent by manurance. The graves have not been opened for gold, the mines not broken with sledges, nor their images pulled down out of their temples. It hath never been entered by any army of strength, and never conquered or possessed by any Christian prince. It is besides so defensible, that if two forts be builded in one of the provinces which I have seen, the flood setteth in so near the bank, where the channel also lieth, that no ship can pass up but within a pike’s length of the artillery, first of the one, and afterwards of the other. Which two forts will be a sufficient guard both to the empire of Inga, and to an hundred other several kingdoms, lying within the said river, even to the city of Quito in Peru.

There is therefore great difference between the easiness of the conquest of Guiana, and the defence of it being conquered, and the West or East Indies. Guiana hath but one entrance by the sea, if it hath that, for any vessels of burden. So as whosoever shall first possess it, it shall be found unaccessible for any enemy, except he come in wherries, barges, or canoas, or else in flat-bottomed boats; and if he do offer to enter it in that manner, the woods are so thick 200 miles together upon the rivers of such entrance, as a mouse cannot sit in a boat unhit from the bank. By land it is more impossible to approach; for it hath the strongest situation of any region under the sun, and it is so environed with impassable mountains on every side, as it is impossible to victual any company in the passage. Which hath been well proved by the Spanish nation, who since the conquest of Peru have never left five years free from attempting this empire, or discovering some way into it; and yet of three-and-twenty several gentlemen, knights, and noblemen, there was never any that knew which way to lead an army by land, or to conduct ships by sea, anything near the said country. Orellana, of whom the river of Amazons taketh name, was the first, and Don Antonio de Berreo, whom we displanted, the last: and I doubt much whether he himself or any of his yet know the best way into the said empire. It can therefore hardly be regained, if any strength be formerly set down, but in one or two places, and but two or three crumsters or galleys built and furnished upon the river within. The West Indies have many ports, watering places, and landings; and nearer than 300 miles to Guiana, no man can harbour a ship, except he know one only place, which is not learned in haste, and which I will undertake there is not any one of my companies that knoweth, whosoever hearkened most after it.

Besides, by keeping one good fort, or building one town of strength, the whole empire is guarded; and whatsoever companies shall be afterwards planted within land without either wood, bog, or mountain. Whereas in the West Indies there are few towns or provinces that can succour or relieve one the other by land or sea. By land the countries are either desert, mountainous, or strong enemies. By sea, if any man invade to the eastward, those to the west cannot in many months turn against the breeze and eastern wind. Besides, the Spaniards are therein so dispersed as they are nowhere strong, but in Nueva Espana only; the sharp mountains, the thorns, and poisoned prickles, the sandy and deep ways in the valleys, the smothering heat and air, and want of water in other places are their only and best defence; which, because those nations that invade them are not victualled or provided to stay, neither have any place to friend adjoining, do serve them instead of good arms and great multitudes.

The West Indies were first offered her Majesty’s grandfather by Columbus, a stranger, in whom there might be doubt of deceit; and besides it was then thought incredible that there were such and so many lands and regions never written of before. This Empire is made known to her Majesty by her own vassal, and by him that oweth to her more duty than an ordinary subject; so that it shall ill sort with the many graces and benefits which I have received to abuse her Highness, either with fables or imaginations. The country is already discovered, many nations won to her Majesty’s love and obedience, and those Spaniards which have latest and longest laboured about the conquest, beaten out, discouraged, and disgraced, which among these nations were thought invincible. Her Majesty may in this enterprise employ all those soldiers and gentlemen that are younger brethren, and all captains and chieftains that want employment, and the charge will be only the first setting out in victualling and arming them; for after the first or second year I doubt not but to see in London a Contractation-House of more receipt for Guiana than there is now in Seville for the West Indies.

And I am resolved that if there were but a small army afoot in Guiana, marching towards Manoa, the chief city of Inga, he would yield to her Majesty by composition so many hundred thousand pounds yearly as should both defend all enemies abroad, and defray all expenses at home; and that he would besides pay a garrison of three or four thousand soldiers very royally to defend him against other nations. For he cannot but know how his predecessors, yea, how his own great uncles, Guascar and Atabalipa, sons to Guiana-Capac, emperor of Peru, were, while they contended for the empire, beaten out by the Spaniards, and that both of late years and ever since the said conquest, the Spaniards have sought the passages and entry of his country; and of their cruelties used to the borderers he cannot be ignorant. In which respects no doubt but he will be brought to tribute with great gladness; if not, he hath neither shot nor iron weapon in all his empire, and therefore may easily be conquered.

And I further remember that Berreo confessed to me and others, which I protest before the Majesty of God to be true, that there was found among the prophecies empire, that from Inglatierra those Ingas should be again in time to come restored, and delivered from the servitude of the said conquerors. And I hope, as we with these few hands have displanted the first garrison, and driven them out of the said country, so her Majesty will give order for the rest, and either defend it, and hold it as tributary, or conquer and keep it as empress of the same. For whatsoever prince shall possess it, shall be greatest; and if the king of Spain enjoy it, he will become unresistible. Her Majesty hereby shall confirm and strengthen the opinions of all nations as touching her great and princely actions. And where the south border of Guiana reacheth to the dominion and empire of the Amazons, those women shall hereby hear the name of a virgin, which is not only able to defend her own territories and her neighbours, but also to invade and conquer so great empires and so far removed.

To speak more at this time I fear would be but troublesome: I trust in God, this being true, will suffice, and that he which is King of all Kings, and Lord of Lords, will put it into her heart which is Lady of Ladies to possess it. If not, I will judge those men worthy to be kings thereof, that by her grace and leave will undertake it of themselves.

2.9.7 Reading and Review Questions

1. To what degree, if any, do you see Raleigh expressing his society’s values in his poetry and prose, and how? To what degree, if any, do you see Raleigh expressing personal values in his poetry and prose, and how? How do these expressions compare to More’s or Spenser’s?

2. What attitude towards the pastoral tradition in literature does “The Nymph’s Reply” convey, and how?

3. Considering Raleigh’s determined pursuit of glory, fame, courtly influence, and wealth, how seriously, if at all, do you think he intends his readers to take the condemnations in “The Lie?”

4. In “To Cynthia,” how, if at all, does Raleigh obliquely refer to Elizabeth I, and why? What relationship, if any, between the two might we infer from this poem, and why? How does his reference to Elizabeth I compare to Spenser’s?

5. In “The Discoverie,” how, if at all, does Raleigh persuade his readers of the truth of what he is describing? What rhetorical devices, if any, does he use? What appeals to logic, if any, does he use? With what detail does Raleigh describe the native peoples, and why?