13 1.13-1.13.4 Geoffrey Chaucer

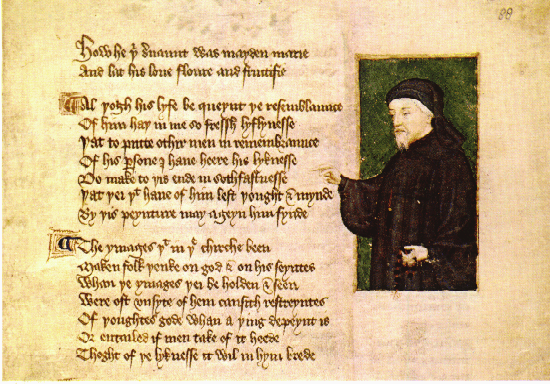

1.13 GEOFFREY CHAUCER

(ca. 1340-1400)

Geoffrey Chaucer’s influence on later British literature is difficult to overstate. The most important English writer before Shakespeare (who re-wrote Chaucer’s version of the Troilus and Criseyde story), Chaucer introduced new words into English (such as “cosmos”), and his stories draw on a wealth of previous authors, especially Ovid and Boccaccio. Part of his importance to English literature is that Chaucer chose to write in English, despite his understanding of French, Italian, and Latin; his friend and contemporary poet John Gower chose to write in French, Latin, and English, specifically because he was not sure which language would preserve his writing the best. Chaucer is part of a line of poets who chose to write in their own country’s vernacular. In the ancient world, Virgil had written in Latin, rather than in Greek, despite Greek’s prestige at the time, and in doing so had elevated Latin to a prestigious literary language. Dante had followed the same pattern with Italian. After Chaucer, Cervantes would write in his Don Quixote that the poet’s goal should be to make the literature of his own language competitive with that of any other country, citing poets such as Virgil. Chaucer lays the foundation for the English writers who followed him.

Chaucer was a product of what we would now call the middle class, although that term did not exist in Chaucer’s time. Medieval England followed the three estates model, recognizing only aristocracy, clergy, and the workers. As certain groups became more prosperous, the usual goal was to work for and marry into the lower levels of the aristocracy, which is the route that Chaucer takes. Chaucer received an excellent education, and he had the opportunity to serve as a page in the household of the Countess of Ulster. Chaucer married Philippa de Roet, a lady-in-waiting, whose sister Katherine was first the mistress and then the third wife of John of Gaunt (one of the sons of Edward III and Chaucer’s patron). Chaucer served as a soldier when younger, and he held a variety of jobs over the years: diplomat, customs official, justice of the peace, and member of parliament (MP) for Kent, among others, all while writing. Although Chaucer received royal annuities from both Edward III and Richard II, his most important patron remained John of Gaunt, whose son became Henry IV after deposing Richard II in 1399 (and granted Chaucer an annuity shortly thereafter).

For individuals who were not as highly educated as Chaucer, it was a more difficult prospect to advance. The British class system was not based on money, but on bloodlines; a dirt-poor aristocrat was still an aristocrat, while a rich peasant was still a peasant. Chaucer’s Miller in The Canterbury Tales is keenly aware of this distinction. The Miller objects to the idea that a “better man” (line 22) than he is—namely, the Monk—should tell the next tale, claiming to have a story every bit as good as the tale just finished by the Knight. If he is insulted by being forced to yield to the Monk, the Miller threatens to leave the pilgrimage. Several of the middle class characters show a similar reluctance to accept a lower place in the social hierarchy.

Social class plays a role in Chaucer’s Parlement of Fowles (sometimes called The Parliament of Birds in modern translations), which is an example of one of Chaucer’s dream visions. Dream visions were popular with medieval writers because anything can happen in a dream; the narrator can talk to anyone from the past, or find himself in any location, and the writer can

present the action metaphorically, rather than literally. As in all of his poems, a version of Chaucer appears as the narrator of the story: a socially-awkward book lover who portrays himself as a romantic failure. The poem begins with the narrator reading Cicero’s Dream of Scipio (Somnium Scipionis), after which he falls asleep. In his dream, Scipio Africanus the Elder leads him to a garden gate with inscriptions on it (a parallel to Virgil guiding Dante to the gate of Hell in Inferno). Inside, the narrator first encounters the temple of Venus, and then a gathering of birds presided over by Nature. The birds represent various groups in society, with the birds of prey as the nobility. Three male eagles use the language of courtly love poetry to attempt to win the same formel (female) eagle; when there is no immediate choice made, all the birds of lower class levels begin to offer their comic opinions. Courtly love poetry often focuses on the male perspective exclusively; the female is the object to be obtained, and she usually is not given a voice (or, ultimately, a choice) in the matter. The Parliament of Fowles gives the female a voice, if not necessarily a choice, about whether she wants any of them.

The Canterbury Tales is Chaucer’s masterpiece of social satire. The story was incomplete at his death (although scholars have debated whether the story is, in some ways, thematically complete). Unlike previous versions of frame tales, such as Boccaccio’s Decameron, Chaucer’s frame is every bit as important as the stories. The General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales may be about group on a pilgrimage to Canterbury, but the travelers do nothing that identifies them as pilgrims; they eat too much instead of fasting, get drunk, wear fancy clothes, ride instead of walk, and tell stories instead of saying prayers (plus it begins and will end in a tavern). The narrator offers no overt judgment of the pilgrims, while providing enough information in the General Prologue for the audience to judge for themselves. Among the many topics satirized in Chaucer’s work is, once again, courtly love. The Miller’s Tale is a mocking revision of the genre by the Miller, who is responding to the story of courtly love that had just been told by the Knight. The Wife of Bath’s Tale and The Franklin’s Tale both offer fascinating alternatives to the regular courtly love scenario, while the Pardoner’s Tale takes aim at every vice imaginable. Chaucer may follow standard medieval procedure by offering a Retraction at the end of The Canterbury Tales (asking forgiveness for anything he wrote that tended towards sin), but it is worth noting that the reader has finished his collection of stories before reaching it.

1.13.1 Bibliography

Sections taken from my introduction to Chaucer in The Compact Anthology of World

Literature and World Literature I: Beginnings to 1650

1.13.2 The Parliament of Birds

(ca. 1381-1382)

The life so short, the craft so long to learn,

Th’assay so hard, so sharp the conquering,

The dreadful joy, alway that flits so yern;

All this mean I by Love, that my feeling

Astoneth with his wonderful working,

So sore, y-wis, that, when I on him think,

Naught wit I well whether I fleet or sink,

For all be that I know not Love indeed, albeit,

Nor wot how that he quiteth folk their hire,

Yet happeth me full oft in books to read their service

Of his miracles, and of his cruel ire;

There read I well, he will be lord and sire;

I dare not saye, that his strokes be sore;

But God save such a lord! I can no more.

Of usage, what for lust and what for lore,

On bookes read I oft, as I you told.

But wherefore speak I alle this? Not yore

Agone, it happed me for to behold

Upon a book written with letters old;

And thereupon, a certain thing to learn,

The longe day full fast I read and yern.

For out of the old fieldes, as men saith,

Cometh all this new corn, from year to year;

And out of olde bookes, in good faith,

Cometh all this new science that men lear.

But now to purpose as of this mattere:

To reade forth it gan me so delight,

That all the day me thought it but a lite.

This book, of which I make mention,

Entitled was right thus, as I shall tell;

“Tullius, of the Dream of Scipion:”

Chapters seven it had, of heav’n, and hell,

And earth, and soules that therein do dwell;

Of which, as shortly as I can it treat,

Of his sentence I will you say the great.

First telleth it, when Scipio was come

To Africa, how he met Massinisse,

That him for joy in armes hath y-nome.

Then telleth he their speech, and all the bliss

That was between them till the day gan miss.

And how his ancestor Africane so dear

Gan in his sleep that night to him appear.

Then telleth it, that from a starry place

How Africane hath him Carthage y-shew’d,

And warned him before of all his grace

And said him, what man, learned either lewd,

That loveth common profit, well y-thew’d,

He should unto a blissful place wend,

Where as the joy is without any end.

Then asked he, if folk that here be dead

Have life, and dwelling, in another place?

And Africane said, “Yea, withoute dread;”

And how our present worldly lives’ space

Meant but a manner death, what way we trace;

And rightful folk should go, after they die,

To Heav’n; and showed him the galaxy.

Then show’d he him the little earth that here is,

To regard the heaven’s quantity;

And after show’d he him the nine spheres;

And after that the melody heard he,

That cometh of those spheres thrice three,

That wells of music be and melody

In this world here, and cause of harmony.

Then said he him, since earthe was so lite,

And full of torment and of harde grace,

That he should not him in this world delight.

Then told he him, in certain yeares’ space,

That ev’ry star should come into his place,

Where it was first; and all should out of mind,

That in this world is done of all mankind.

Then pray’d him Scipio, to tell him all

The way to come into that Heaven’s bliss;

And he said: “First know thyself immortal,

And look aye busily that thou work and wiss

To common profit, and thou shalt not miss

To come swiftly unto that place dear,

That full of bliss is, and of soules clear.

“And breakers of the law, the sooth to sayn,

And likerous folk, after that they be dead,

Shall whirl about the world always in pain,

Till many a world be passed, out of dread;

And then, forgiven all their wicked deed,

They shalle come unto that blissful place,

To which to come God thee sende grace!”

The day gan failen, and the darke night,

That reaveth beastes from their business,

Berefte me my book for lack of light,

And to my bed I gan me for to dress,

Full fill’d of thought and busy heaviness;

For both I hadde thing which that I n’old,

And eke I had not that thing that I wo’ld.

But, finally, my spirit at the last,

Forweary of my labour all that day,

Took rest, that made me to sleepe fast;

And in my sleep I mette, as that I say,

How Africane, right in the self array

That Scipio him saw before that tide,

Was come, and stood right at my bedde’s side.

The weary hunter, sleeping in his bed,

To wood again his mind goeth anon;

The judge dreameth how his pleas be sped;

The carter dreameth how his cartes go’n;

The rich of gold, the knight fights with his fone;

The sicke mette he drinketh of the tun;

The lover mette he hath his lady won.

I cannot say, if that the cause were,

For I had read of Africane beforn,

That made me to mette that he stood there;

But thus said he; “Thou hast thee so well borne

In looking of mine old book all to-torn,

Of which Macrobius raught not a lite,

That somedeal of thy labour would I quite.”

Cytherea, thou blissful Lady sweet!

That with thy firebrand dauntest when thee lest,

That madest me this sweven for to mette,

Be thou my help in this, for thou may’st best!

As wisly as I saw the north-north-west,

When I began my sweven for to write,

So give me might to rhyme it and endite.

This foresaid Africane me hent anon,

And forth with him unto a gate brought

Right of a park, walled with greene stone;

And o’er the gate, with letters large y-wrought,

There were verses written, as me thought,

On either half, of full great difference,

Of which I shall you say the plain sentence.

“Through me men go into the blissful place

Of hearte’s heal and deadly woundes’ cure;

Through me men go unto the well of grace;

Where green and lusty May shall ever dure;

This is the way to all good adventure;

Be glad, thou reader, and thy sorrow off cast;

All open am I; pass in and speed thee fast.”

“Through me men go,” thus spake the other side,

“Unto the mortal strokes of the spear,

Of which disdain and danger is the guide;

There never tree shall fruit nor leaves bear;

This stream you leadeth to the sorrowful weir,

Where as the fish in prison is all dry;

Th’eschewing is the only remedy.”

These verses of gold and azure written were,

On which I gan astonish’d to behold;

For with that one increased all my fear,

And with that other gan my heart to bold;

That one me het, that other did me cold;

No wit had I, for error, for to choose

To enter or fly, or me to save or lose.

Right as betwixten adamantes two

Of even weight, a piece of iron set,

Ne hath no might to move to nor fro;

For what the one may hale, the other let;

So far’d I, that n’ist whether me was bet

T’ enter or leave, till Africane, my guide, better for me

Me hent and shov’d in at the gates wide.

And said, “It standeth written in thy face,

Thine error, though thou tell it not to me;

But dread thou not to come into this place;

For this writing is nothing meant by thee,

Nor by none, but he Love’s servant be; unless

For thou of Love hast lost thy taste, I guess,

As sick man hath of sweet and bitterness.

“But natheless, although that thou be dull,

That thou canst not do, yet thou mayest see;

For many a man that may not stand a pull,

Yet likes it him at wrestling for to be,

And deeme whether he doth bet, or he;

And, if thou haddest cunning to endite,

I shall thee showe matter of to write.”

With that my hand in his he took anon,

Of which I comfort caught, and went in fast.

But, Lord! so I was glad and well-begone!

For over all, where I my eyen cast,

Were trees y-clad with leaves that ay shall last,

Each in his kind, with colour fresh and green

As emerald, that joy it was to see’n.

The builder oak; and eke the hardy ash;

The pillar elm, the coffer unto carrain;

The box, pipe tree; the holm, to whippe’s lash

The sailing fir; the cypress death to plain;

The shooter yew; the aspe for shaftes plain;

Th’olive of peace, and eke the drunken vine;

The victor palm; the laurel, too, divine.

A garden saw I, full of blossom’d boughes,

Upon a river, in a greene mead,

Where as sweetness evermore enow is,

With flowers white, blue, yellow, and red,

And colde welle streames, nothing dead,

That swamme full of smalle fishes light,

With finnes red, and scales silver bright.

On ev’ry bough the birdes heard I sing,

With voice of angels in their harmony,

That busied them their birdes forth to bring;

The pretty conies to their play gan hie;

And further all about I gan espy

The dreadful roe, the buck, the hart, and hind,

Squirrels, and beastes small, of gentle kind.

Of instruments of stringes in accord

Heard I so play a ravishing sweetness,

That God, that Maker is of all and Lord,

Ne hearde never better, as I guess:

Therewith a wind, unneth it might be less,

Made in the leaves green a noise soft,

Accordant the fowles’ song on loft.

Th’air of the place so attemper was,

That ne’er was there grievance of hot nor cold;

There was eke ev’ry wholesome spice and grass,

Nor no man may there waxe sick nor old:

Yet was there more joy a thousand fold

Than I can tell, or ever could or might;

There ever is clear day, and never night.

Under a tree, beside a well, I sey

Cupid our lord his arrows forge and file;

And at his feet his bow all ready lay;

And well his daughter temper’d, all the while,

The heades in the well; and with her wile

She couch’d them after, as they shoulde serve

Some for to slay, and some to wound and kerve.

Then was I ware of Pleasance anon right,

And of Array, and Lust, and Courtesy,

And of the Craft, that can and hath the might

To do by force a wight to do folly;

Disfigured was she, I will not lie;

And by himself, under an oak, I guess,

Saw I Delight, that stood with Gentleness.

Then saw I Beauty, with a nice attire,

And Youthe, full of game and jollity,

Foolhardiness, Flattery, and Desire,

Messagerie, and Meed, and other three;

Their names shall not here be told for me:

And upon pillars great of jasper long

I saw a temple of brass y-founded strong.

And [all] about the temple danc’d alway

Women enough, of whiche some there were

Fair of themselves, and some of them were gay

In kirtles all dishevell’d went they there;

That was their office ever, from year to year;

And on the temple saw I, white and fair,

Of doves sitting many a thousand pair.

Before the temple door, full soberly,

Dame Peace sat, a curtain in her hand;

And her beside, wonder discreetely,

Dame Patience sitting there I fand,

With face pale, upon a hill of sand;

And althernext, within and eke without,

Behest, and Art, and of their folk a rout.

Within the temple, of sighes hot as fire

I heard a swough, that gan aboute ren,

Which sighes were engender’d with desire,

That made every hearte for to bren

Of newe flame; and well espied I then,

That all the cause of sorrows that they dree

Came of the bitter goddess Jealousy.

The God Priapus saw I, as I went

Within the temple, in sov’reign place stand,

In such array, as when the ass him shent

With cry by night, and with sceptre in hand:

Full busily men gan assay and fand

Upon his head to set, of sundry hue,

Garlandes full of freshe flowers new.

And in a privy corner, in disport,

Found I Venus and her porter Richess,

That was full noble and hautain of her port;

Dark was that place, but afterward lightness

I saw a little, unneth it might be less;

And on a bed of gold she lay to rest,

Till that the hote sun began to west.

Her gilded haires with a golden thread

Y-bounden were, untressed, as she lay;

And naked from the breast unto the head

Men might her see; and, soothly for to say,

The remnant cover’d, welle to my pay,

Right with a little kerchief of Valence;

There was no thicker clothe of defence.

The place gave a thousand savours swoot;

And Bacchus, god of wine, sat her beside;

And Ceres next, that doth of hunger boot;

And, as I said, amiddes lay Cypride,

To whom on knees the younge folke cried

To be their help: but thus I let her lie,

And farther in the temple gan espy,

That, in despite of Diana the chaste,

Full many a bowe broke hung on the wall,

Of maidens, such as go their time to waste

In her service: and painted over all

Of many a story, of which I touche shall

A few, as of Calist’, and Atalant’,

And many a maid, of which the name I want.

Semiramis, Canace, and Hercules,

Biblis, Dido, Thisbe and Pyramus,

Tristram, Isoude, Paris, and Achilles,

Helena, Cleopatra, Troilus,

Scylla, and eke the mother of Romulus;

All these were painted on the other side,

And all their love, and in what plight they died.

When I was come again into the place

That I of spake, that was so sweet and green,

Forth walk’d I then, myselfe to solace:

Then was I ware where there sat a queen,

That, as of light the summer Sunne sheen

Passeth the star, right so over measure

She fairer was than any creature.

And in a lawn, upon a hill of flowers,

Was set this noble goddess of Nature;

Of branches were her halles and her bowers

Y-wrought, after her craft and her measure;

Nor was there fowl that comes of engendrure

That there ne were prest, in her presence,

To take her doom, and give her audience.

For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day,

When ev’ry fowl cometh to choose her make,

Of every kind that men thinken may;

And then so huge a noise gan they make,

That earth, and sea, and tree, and ev’ry lake,

So full was, that unnethes there was space

For me to stand, so full was all the place.

And right as Alain, in his Plaint of Kind,

Deviseth Nature of such array and face;

In such array men mighte her there find.

This noble Emperess, full of all grace,

Bade ev’ry fowle take her owen place,

As they were wont alway, from year to year,

On Saint Valentine’s Day to stande there.

That is to say, the fowles of ravine

Were highest set, and then the fowles smale,

That eaten as them Nature would incline;

As worme-fowl, of which I tell no tale;

But waterfowl sat lowest in the dale,

And fowls that live by seed sat on the green,

And that so many, that wonder was to see’n.

There mighte men the royal eagle find,

That with his sharpe look pierceth the Sun;

And other eagles of a lower kind,

Of which that clerkes well devise con;

There was the tyrant with his feathers dun can describe

And green, I mean the goshawk, that doth pine

To birds, for his outrageous ravine.

The gentle falcon, that with his feet distraineth

The kinge’s hand; the hardy sperhawk eke,

The quaile’s foe; the merlion that paineth

Himself full oft the larke for to seek;

There was the dove, with her eyen meek;

The jealous swan, against his death that singeth;

The owl eke, that of death the bode bringeth

The crane, the giant, with his trumpet soun’;

The thief the chough; and eke the chatt’ring pie;

The scorning jay; the eel’s foe the heroun;

The false lapwing, full of treachery;

The starling, that the counsel can betray;

The tame ruddock, and the coward kite;

The cock, that horologe is of thorpes lite.

The sparrow, Venus’ son; the nightingale,

That calleth forth the freshe leaves new;

The swallow, murd’rer of the bees smale,

That honey make of flowers fresh of hue;

The wedded turtle, with his hearte true;

The peacock, with his angel feathers bright;

The pheasant, scorner of the cock by night;

The waker goose; the cuckoo ever unkind;

The popinjay, full of delicacy;

The drake, destroyer of his owen kind;

The stork, the wreaker of adultery;

The hot cormorant, full of gluttony;

The raven and the crow, with voice of care;

The throstle old; and the frosty fieldfare.

What should I say? Of fowls of ev’ry kind

That in this world have feathers and stature,

Men mighten in that place assembled find,

Before that noble goddess of Nature;

And each of them did all his busy cure

Benignely to choose, or for to take,

By her accord, his formel or his make.

But to the point. Nature held on her hand

A formel eagle, of shape the gentilest

That ever she among her workes fand,

The most benign, and eke the goodliest;

In her was ev’ry virtue at its rest,

So farforth that Nature herself had bliss

To look on her, and oft her beak to kiss.

Nature, the vicar of th’Almighty Lord, —

That hot, cold, heavy, light, and moist, and dry,

Hath knit, by even number of accord, —

In easy voice began to speak, and say:

“Fowles, take heed of my sentence,” I pray;

And for your ease, in furth’ring of your need,

As far as I may speak, I will me speed.

“Ye know well how, on Saint Valentine’s Day,

By my statute, and through my governance,

Ye choose your mates, and after fly away

With them, as I you pricke with pleasance;

But natheless, as by rightful ordinance,

May I not let, for all this world to win,

But he that most is worthy shall begin.

“The tercel eagle, as ye know full weel,

The fowl royal, above you all in degree,

The wise and worthy, secret, true as steel,

The which I formed have, as ye may see,

In ev’ry part, as it best liketh me, —

It needeth not his shape you to devise, —

He shall first choose, and speaken in his guise.

“And, after him, by order shall ye choose,

After your kind, evereach as you liketh;

And as your hap is, shall ye win or lose;

But which of you that love most entriketh,

God send him her that sorest for him siketh.”

And therewithal the tercel gan she call,

And said, “My son, the choice is to thee fall.

“But natheless, in this condition

Must be the choice of ev’reach that is here,

That she agree to his election,

Whoso he be, that shoulde be her fere;

This is our usage ay, from year to year;

And whoso may at this time have this grace,

In blissful time he came into this place.”

With head inclin’d, and with full humble cheer,

This royal tercel spake, and tarried not:

“Unto my sov’reign lady, and not my fere,

I chose and choose, with will, and heart, and thought,

The formel on your hand, so well y-wrought,

Whose I am all, and ever will her serve,

Do what her list, to do me live or sterve.

“Beseeching her of mercy and of grace,

As she that is my lady sovereign,

Or let me die here present in this place,

For certes long may I not live in pain;

For in my heart is carven ev’ry vein:

Having regard only unto my truth, wounded with love

My deare heart, have on my woe some ruth.

“And if that I be found to her untrue,

Disobeisant, or wilful negligent,

Avaunter, or in process love a new,

I pray to you, this be my judgement, of time

That with these fowles I be all to-rent,

That ilke day that she me ever find

To her untrue, or in my guilt unkind.

“And since none loveth her so well as I,

Although she never of love me behet,

Then ought she to be mine, through her mercy;

For other bond can I none on her knit;

For weal or for woe, never shall I let

To serve her, how far so that she wend;

Say what you list, my tale is at an end.”

Right as the freshe redde rose new

Against the summer Sunne colour’d is,

Right so, for shame, all waxen gan the hue

Of this formel, when she had heard all this;

Neither she answer’d well, nor said amiss,

So sore abashed was she, till Nature either well or ill

Said, “Daughter, dread you not, I you assure.”

Another tercel eagle spake anon,

Of lower kind, and said that should not be;

“I love her better than ye do, by Saint John!

Or at the least I love her as well as ye,

And longer have her serv’d in my degree;

And if she should have lov’d for long loving,

To me alone had been the guerdoning.

“I dare eke say, if she me finde false,

Unkind, janglere, rebel in any wise,

Or jealous, do me hange by the halse;

And but I beare me in her service

As well ay as my wit can me suffice,

From point to point, her honour for to save,

Take she my life and all the good I have.”

A thirde tercel eagle answer’d tho:

“Now, Sirs, ye see the little leisure here;

For ev’ry fowl cries out to be ago

Forth with his mate, or with his lady dear;

And eke Nature herselfe will not hear,

For tarrying her, not half that I would say;

And but I speak, I must for sorrow dey.

Of long service avaunt I me no thing,

But as possible is me to die to-day,

For woe, as he that hath been languishing

This twenty winter; and well happen may

A man may serve better, and more to pay,

In half a year, although it were no more.

Than some man doth that served hath full yore.

“I say not this by me for that I can

Do no service that may my lady please;

But I dare say, I am her truest man

As to my doom, and fainest would her please;

At shorte words, until that death me seize,

I will be hers, whether I wake or wink.

And true in all that hearte may bethink.”

Of all my life, since that day I was born,

So gentle plea, in love or other thing,

Ye hearde never no man me beforn;

Whoso that hadde leisure and cunning

For to rehearse their cheer and their speaking:

And from the morrow gan these speeches last,

Till downward went the Sunne wonder fast.

The noise of fowles for to be deliver’d

So loude rang, “Have done and let us wend,”

That well ween’d I the wood had all to-shiver’d:

“Come off!” they cried; “alas! ye will us shend!

When will your cursed pleading have an end?

How should a judge either party believe,

For yea or nay, withouten any preve?”

The goose, the duck, and the cuckoo also,

So cried “keke, keke,” “cuckoo,” “queke queke,” high,

That through mine ears the noise wente tho.

The goose said then, “All this n’is worth a fly!

But I can shape hereof a remedy;

And I will say my verdict, fair and swith,

For water-fowl, whoso be wroth or blith.”

“And I for worm-fowl,” said the fool cuckow;

For I will, of mine own authority,

For common speed, take on me the charge now;

For to deliver us is great charity.”

“Ye may abide a while yet, pardie,”

Quoth then the turtle; “if it be your will

A wight may speak, it were as good be still.

“I am a seed-fowl, one th’unworthiest,

That know I well, and the least of cunning;

But better is, that a wight’s tongue rest,

Than entremette him of such doing meddle with

Of which he neither rede can nor sing; counsel

And who it doth, full foul himself accloyeth,

For office uncommanded oft annoyeth.”

Nature, which that alway had an ear

To murmur of the lewedness behind,

With facond voice said, “Hold your tongues there,

And I shall soon, I hope, a counsel find,

You to deliver, and from this noise unbind;

I charge of ev’ry flock ye shall one call,

To say the verdict of you fowles all.”

The tercelet said then in this mannere;

“Full hard it were to prove it by reason,

Who loveth best this gentle formel here;

For ev’reach hath such replication,

That by skilles may none be brought adown;

I cannot see that arguments avail;

Then seemeth it that there must be battaile.”

“All ready!” quoth those eagle tercels tho;

“Nay, Sirs!” quoth he; “if that I durst it say,

Ye do me wrong, my tale is not y-do,done

For, Sirs, — and take it not agrief, I pray, —

It may not be as ye would, in this way:

Ours is the voice that have the charge in hand,

And to the judges’ doom ye muste stand.

“And therefore ‘Peace!’ I say; as to my wit,

Me woulde think, how that the worthiest

Of knighthood, and had longest used it,

Most of estate, of blood the gentilest,

Were fitting most for her, if that her lest

And, of these three she knows herself, I trow,

Which that he be; for it is light to know.” easy

The water-fowles have their heades laid

Together, and of short advisement, after brief deliberation

When evereach his verdict had y-said

They saide soothly all by one assent,

How that “The goose with the facond gent,

That so desired to pronounce our need,

Shall tell our tale;” and prayed God her speed.

And for those water-fowles then began

The goose to speak. and in her cackeling

She saide, “Peace, now! take keep ev’ry man,

And hearken what reason I shall forth bring;

My wit is sharp, I love no tarrying;

I say I rede him, though he were my brother,

But she will love him, let him love another!”

“Lo! here a perfect reason of a goose!”

Quoth the sperhawke. “Never may she the!

Lo such a thing ’tis t’have a tongue loose!

Now, pardie: fool, yet were it bet for thee

Have held thy peace, than show’d thy nicety;

It lies not in his wit, nor in his will,

But sooth is said, a fool cannot be still.”

The laughter rose of gentle fowles all;

And right anon the seed-fowls chosen had

The turtle true, and gan her to them call,

And prayed her to say the soothe sad

Of this mattere, and asked what she rad;

And she answer’d, that plainly her intent

She woulde show, and soothly what she meant.

“Nay! God forbid a lover shoulde change!”

The turtle said, and wax’d for shame all red:

“Though that his lady evermore be strange,

Yet let him serve her ay, till he be dead;

For, sooth, I praise not the goose’s rede

For, though she died, I would none other make;

I will be hers till that the death me take.”

“Well bourded!” quoth the ducke, “by my hat!

That men should loven alway causeless,

Who can a reason find, or wit, in that?

Danceth he merry, that is mirtheless?

Who shoulde reck of that is reckeless?

Yea! queke yet,” quoth the duck, “full well and fair! no care for him

There be more starres, God wot, than a pair!”

“Now fy, churl!” quoth the gentle tercelet,

“Out of the dunghill came that word aright;

Thou canst not see which thing is well beset;

Thou far’st by love, as owles do by light,—

The day them blinds, full well they see by night;

Thy kind is of so low a wretchedness,

That what love is, thou caust not see nor guess.”

Then gan the cuckoo put him forth in press,

For fowl that eateth worm, and said belive:

“So I,” quoth he, “may have my mate in peace,

I recke not how longe that they strive.

Let each of them be solain all their life;

This is my rede, since they may not accord;

This shorte lesson needeth not record.”

“Yea, have the glutton fill’d enough his paunch,

Then are we well!” saide the emerlon;

“Thou murd’rer of the heggsugg, on the branch

That brought thee forth, thou most rueful glutton,

Live thou solain, worme’s corruption!

For no force is to lack of thy nature;

Go! lewed be thou, while the world may dare!”

“Now peace,” quoth Nature, “I commande here;

For I have heard all your opinion,

And in effect yet be we ne’er the nere.

But, finally, this is my conclusion, —

That she herself shall have her election

Of whom her list, whoso be wroth or blith;

Him that she chooseth, he shall her have as swith.

“For since it may not here discussed be

Who loves her best, as said the tercelet,

Then will I do this favour t’ her, that she

Shall have right him on whom her heart is set,

And he her, that his heart hath on her knit:

This judge I, Nature, for I may not lie

To none estate; I have none other eye.

“But as for counsel for to choose a make,

If I were Reason, [certes] then would I

Counsaile you the royal tercel take,

As saith the tercelet full skillfully,

As for the gentilest, and most worthy,

Which I have wrought so well to my pleasance,

That to you it ought be a suffisance.”

With dreadful voice the formel her answer’d:

“My rightful lady, goddess of Nature,

Sooth is, that I am ever under your yerd,

As is every other creature,

And must be yours, while that my life may dure;

And therefore grante me my firste boon,

And mine intent you will I say right soon.”

“I grant it you,” said she; and right anon

This formel eagle spake in this degree:

“Almighty queen, until this year be done

I aske respite to advise me;

And after that to have my choice all free;

This is all and some that I would speak and say;

Ye get no more, although ye do me dey.

“I will not serve Venus, nor Cupide,

For sooth as yet, by no manner [of] way.”

“Now since it may none other ways betide,”

Quoth Dame Nature, “there is no more to say;

Then would I that these fowles were away,

Each with his mate, for longer tarrying here.”

And said them thus, as ye shall after hear.

“To you speak I, ye tercels,” quoth Nature;

“Be of good heart, and serve her alle three;

A year is not so longe to endure;

And each of you pain him in his degree

For to do well, for, God wot, quit is she

From you this year, what after so befall;

This entremess is dressed for you all.”

And when this work y-brought was to an end,

To ev’ry fowle Nature gave his make,

By even accord, and on their way they wend:

And, Lord! the bliss and joye that they make!

For each of them gan other in his wings take,

And with their neckes each gan other wind,

Thanking alway the noble goddess of Kind.

But first were chosen fowles for to sing,—

As year by year was alway their usance, —

To sing a roundel at their departing,

To do to Nature honour and pleasance;

The note, I trowe, maked was in France;

The wordes were such as ye may here find

The nexte verse, as I have now in mind:

Qui bien aime, tard oublie.

“Now welcome summer, with thy sunnes soft,

That hast these winter weathers overshake

Saint Valentine, thou art full high on loft,

Which driv’st away the longe nightes blake;

Thus singe smalle fowles for thy sake:

Well have they cause for to gladden oft,

Since each of them recover’d hath his make;

Full blissful may they sing when they awake.”

And with the shouting, when their song was do,

That the fowls maden at their flight away,

I woke, and other bookes took me to,

To read upon; and yet I read alway.

I hope, y-wis, to reade so some day,

That I shall meete something for to fare

The bet; and thus to read I will not spare.

1.13.3 Selections from The Canterbury Tales

General Prologue

WHEN that Aprilis, with his showers swoot,

The drought of March hath pierced to the root,

And bathed every vein in such licour,

Of which virtue engender’d is the flower;

When Zephyrus eke with his swoote breath

Inspired hath in every holt and heath

The tender croppes and the younge sun

Hath in the Ram his halfe course y-run,

And smalle fowles make melody,

That sleepen all the night with open eye,

(So pricketh them nature in their corage);

Then longe folk to go on pilgrimages,

And palmers for to seeke strange strands,

To ferne hallows couth in sundry lands;

And specially, from every shire’s end

Of Engleland, to Canterbury they wend,

The holy blissful Martyr for to seek,

That them hath holpen, when that they were sick.

Befell that, in that season on a day,

In Southwark at the Tabard as I lay,

Ready to wenden on my pilgrimage

To Canterbury with devout corage,

At night was come into that hostelry

Well nine and twenty in a company

Of sundry folk, by aventure y-fall

In fellowship, and pilgrims were they all,

That toward Canterbury woulde ride.

The chamber, and the stables were wide,

And well we weren eased at the best.

And shortly, when the sunne was to rest,

So had I spoken with them every one,

That I was of their fellowship anon,

And made forword early for to rise,

To take our way there as I you devise.

But natheless, while I have time and space,

Ere that I farther in this tale pace,

Me thinketh it accordant to reason,

To tell you alle the condition

Of each of them, so as it seemed me,

And which they weren, and of what degree;

And eke in what array that they were in:

And at a Knight then will I first begin.

A KNIGHT there was, and that a worthy man,

That from the time that he first began

To riden out, he loved chivalry,

Truth and honour, freedom and courtesy.

Full worthy was he in his Lorde’s war,

And thereto had he ridden, no man farre,

As well in Christendom as in Heatheness,

And ever honour’d for his worthiness

At Alisandre he was when it was won.

Full often time he had the board begun

Above alle nations in Prusse.

In Lettowe had he reysed, and in Russe,

No Christian man so oft of his degree.

In Grenade at the siege eke had he be

Of Algesir, and ridden in Belmarie.

At Leyes was he, and at Satalie,

When they were won; and in the Greate Sea

At many a noble army had he be.

At mortal battles had he been fifteen,

And foughten for our faith at Tramissene.

In listes thries, and aye slain his foe.

This ilke worthy knight had been also

Some time with the lord of Palatie,

Against another heathen in Turkie:

And evermore he had a sovereign price.

And though that he was worthy he was wise,

And of his port as meek as is a maid.

He never yet no villainy ne said

In all his life, unto no manner wight.

He was a very perfect gentle knight.

But for to telle you of his array,

His horse was good, but yet he was not gay.

Of fustian he weared a gipon,

Alle besmotter’d with his habergeon,

For he was late y-come from his voyage,

And wente for to do his pilgrimage.

With him there was his son, a younge SQUIRE,

A lover, and a lusty bacheler,

With lockes crulle as they were laid in press.

Of twenty year of age he was I guess.

Of his stature he was of even length,

And wonderly deliver, and great of strength.

And he had been some time in chevachie,

In Flanders, in Artois, and Picardie,

And borne him well, as of so little space,

In hope to standen in his lady’s grace.

Embroider’d was he, as it were a mead

All full of freshe flowers, white and red.

Singing he was, or fluting all the day;

He was as fresh as is the month of May.

Short was his gown, with sleeves long and wide.

Well could he sit on horse, and faire ride.

He coulde songes make, and well indite,

Joust, and eke dance, and well pourtray and write.

So hot he loved, that by nightertale

He slept no more than doth the nightingale.

Courteous he was, lowly, and serviceable,

And carv’d before his father at the table.

A YEOMAN had he, and servants no mo’

At that time, for him list ride so

And he was clad in coat and hood of green.

A sheaf of peacock arrows bright and keen

Under his belt he bare full thriftily.

Well could he dress his tackle yeomanly:

His arrows drooped not with feathers low;

And in his hand he bare a mighty bow.

A nut-head had he, with a brown visiage:

Of wood-craft coud he well all the usage:

Upon his arm he bare a gay bracer,

And by his side a sword and a buckler,

And on that other side a gay daggere,

Harnessed well, and sharp as point of spear:

A Christopher on his breast of silver sheen.

An horn he bare, the baldric was of green:

A forester was he soothly as I guess.

There was also a Nun, a PRIORESS,

That of her smiling was full simple and coy;

Her greatest oathe was but by Saint Loy;

And she was cleped Madame Eglentine.

Full well she sang the service divine,

Entuned in her nose full seemly;

And French she spake full fair and fetisly

After the school of Stratford atte Bow,

For French of Paris was to her unknow.

At meate was she well y-taught withal;

She let no morsel from her lippes fall,

Nor wet her fingers in her sauce deep.

Well could she carry a morsel, and well keep,

That no droppe ne fell upon her breast.

In courtesy was set full much her lest.

Her over-lippe wiped she so clean,

That in her cup there was no farthing seen

Of grease, when she drunken had her draught;

Full seemely after her meat she raught:

And sickerly she was of great disport,

And full pleasant, and amiable of port,

And pained her to counterfeite cheer

Of court, and be estately of mannere,

And to be holden digne of reverence.

But for to speaken of her conscience,

She was so charitable and so pitous,

She woulde weep if that she saw a mouse

Caught in a trap, if it were dead or bled.

Of smalle houndes had she, that she fed

With roasted flesh, and milk, and wastel bread.

But sore she wept if one of them were dead,

Or if men smote it with a yarde smart:

And all was conscience and tender heart.

Full seemly her wimple y-pinched was;

Her nose tretis; her eyen gray as glass;

Her mouth full small, and thereto soft and red;

But sickerly she had a fair forehead.

It was almost a spanne broad I trow;

For hardily she was not undergrow.

Full fetis was her cloak, as I was ware.

Of small coral about her arm she bare

A pair of beades, gauded all with green;

And thereon hung a brooch of gold full sheen,

On which was first y-written a crown’d A,

And after, Amor vincit omnia.

Another Nun also with her had she,

That was her chapelleine, and PRIESTES three.

A MONK there was, a fair for the mast’ry

An out-rider, that loved venery;

A manly man, to be an abbot able.

Full many a dainty horse had he in stable:

And when he rode, men might his bridle hear

Jingeling in a whistling wind as clear,

And eke as loud, as doth the chapel bell,

There as this lord was keeper of the cell.

The rule of Saint Maur and of Saint Benet,

Because that it was old and somedeal strait

This ilke monk let olde thinges pace,

And held after the newe world the trace.

He gave not of the text a pulled hen,

That saith, that hunters be not holy men:

Ne that a monk, when he is cloisterless;

Is like to a fish that is waterless;

This is to say, a monk out of his cloister.

This ilke text held he not worth an oyster;

And I say his opinion was good.

Why should he study, and make himselfe wood

Upon a book in cloister always pore,

Or swinken with his handes, and labour,

As Austin bid? how shall the world be served?

Let Austin have his swink to him reserved.

Therefore he was a prickasour aright:

Greyhounds he had as swift as fowl of flight;

Of pricking and of hunting for the hare

Was all his lust, for no cost would he spare.

I saw his sleeves purfil’d at the hand

With gris, and that the finest of the land.

And for to fasten his hood under his chin,

He had of gold y-wrought a curious pin;

A love-knot in the greater end there was.

His head was bald, and shone as any glass,

And eke his face, as it had been anoint;

He was a lord full fat and in good point;

His eyen steep, and rolling in his head,

That steamed as a furnace of a lead.

His bootes supple, his horse in great estate,

Now certainly he was a fair prelate;

He was not pale as a forpined gost:

A fat swan lov’d he best of any roast.

His palfrey was as brown as is a berry.

A FRIAR there was, a wanton and a merry,

A limitour a full solemne man.

In all the orders four is none that can

So much of dalliance and fair language.

He had y-made full many a marriage

Of younge women, at his owen cost.

Unto his order he was a noble post;

Full well belov’d, and familiar was he

With franklins over all in his country,

And eke with worthy women of the town:

For he had power of confession,

As said himselfe, more than a curate,

For of his order he was licentiate.

Full sweetely heard he confession,

And pleasant was his absolution.

He was an easy man to give penance,

There as he wist to have a good pittance:

For unto a poor order for to give

Is signe that a man is well y-shrive.

For if he gave, he durste make avant,

He wiste that the man was repentant.

For many a man so hard is of his heart,

He may not weep although him sore smart.

Therefore instead of weeping and prayeres,

Men must give silver to the poore freres.

His tippet was aye farsed full of knives

And pinnes, for to give to faire wives;

And certainly he had a merry note:

Well could he sing and playen on a rote;

Of yeddings he bare utterly the prize.

His neck was white as is the fleur-de-lis.

Thereto he strong was as a champion,

And knew well the taverns in every town.

And every hosteler and gay tapstere,

Better than a lazar or a beggere,

For unto such a worthy man as he

Accordeth not, as by his faculty,

To have with such lazars acquaintance.

It is not honest, it may not advance,

As for to deale with no such pouraille

But all with rich, and sellers of vitaille.

And ov’r all there as profit should arise,

Courteous he was, and lowly of service;

There n’as no man nowhere so virtuous.

He was the beste beggar in all his house:

And gave a certain farme for the grant,

None of his bretheren came in his haunt.

For though a widow hadde but one shoe,

So pleasant was his In Principio

Yet would he have a farthing ere he went;

His purchase was well better than his rent.

And rage he could and play as any whelp,

In lovedays there could he muchel help.

For there was he not like a cloisterer,

With threadbare cope as is a poor scholer;

But he was like a master or a pope.

Of double worsted was his semicope,

That rounded was as a bell out of press.

Somewhat he lisped for his wantonness,

To make his English sweet upon his tongue;

And in his harping, when that he had sung,

His eyen twinkled in his head aright,

As do the starres in a frosty night.

This worthy limitour was call’d Huberd.

A MERCHANT was there with a forked beard,

In motley, and high on his horse he sat,

Upon his head a Flandrish beaver hat.

His bootes clasped fair and fetisly.

His reasons aye spake he full solemnly,

Sounding alway th’ increase of his winning.

He would the sea were kept for any thing

Betwixte Middleburg and Orewell

Well could he in exchange shieldes sell

This worthy man full well his wit beset;

There wiste no wight that he was in debt,

So estately was he of governance

With his bargains, and with his chevisance.

For sooth he was a worthy man withal,

But sooth to say, I n’ot how men him call.

A CLERK there was of Oxenford also,

That unto logic hadde long y-go.

As leane was his horse as is a rake,

And he was not right fat, I undertake;

But looked hollow, and thereto soberly.

Full threadbare was his overest courtepy,

For he had gotten him yet no benefice,

Ne was not worldly, to have an office.

For him was lever have at his bed’s head

Twenty bookes, clothed in black or red,

Of Aristotle, and his philosophy,

Than robes rich, or fiddle, or psalt’ry.

But all be that he was a philosopher,

Yet hadde he but little gold in coffer,

But all that he might of his friendes hent,

On bookes and on learning he it spent,

And busily gan for the soules pray

Of them that gave him wherewith to scholay

Of study took he moste care and heed.

Not one word spake he more than was need;

And that was said in form and reverence,

And short and quick, and full of high sentence.

Sounding in moral virtue was his speech,

And gladly would he learn, and gladly teach.

A SERGEANT OF THE LAW, wary and wise,

That often had y-been at the Parvis,

There was also, full rich of excellence.

Discreet he was, and of great reverence:

He seemed such, his wordes were so wise,

Justice he was full often in assize,

By patent, and by plein commission;

For his science, and for his high renown,

Of fees and robes had he many one.

So great a purchaser was nowhere none.

All was fee simple to him, in effect

His purchasing might not be in suspect

Nowhere so busy a man as he there was

And yet he seemed busier than he was

In termes had he case’ and doomes all

That from the time of King William were fall.

Thereto he could indite, and make a thing

There coulde no wight pinch at his writing.

And every statute coud he plain by rote

He rode but homely in a medley coat,

Girt with a seint of silk, with barres small;

Of his array tell I no longer tale.

A FRANKELIN was in this company;

White was his beard, as is the daisy.

Of his complexion he was sanguine.

Well lov’d he in the morn a sop in wine.

To liven in delight was ever his won,

For he was Epicurus’ owen son,

That held opinion, that plein delight

Was verily felicity perfite.

An householder, and that a great, was he;

Saint Julian he was in his country.

His bread, his ale, was alway after one;

A better envined man was nowhere none;

Withoute bake-meat never was his house,

Of fish and flesh, and that so plenteous,

It snowed in his house of meat and drink,

Of alle dainties that men coulde think.

After the sundry seasons of the year,

So changed he his meat and his soupere.

Full many a fat partridge had he in mew,

And many a bream, and many a luce in stew

Woe was his cook, but if his sauce were

Poignant and sharp, and ready all his gear.

His table dormant in his hall alway

Stood ready cover’d all the longe day.

At sessions there was he lord and sire.

Full often time he was knight of the shire

An anlace, and a gipciere all of silk,

Hung at his girdle, white as morning milk.

A sheriff had he been, and a countour

Was nowhere such a worthy vavasour

An HABERDASHER, and a CARPENTER,

A WEBBE, a DYER, and a TAPISER,

Were with us eke, cloth’d in one livery,

Of a solemn and great fraternity.

Full fresh and new their gear y-picked was.

Their knives were y-chaped not with brass,

But all with silver wrought full clean and well,

Their girdles and their pouches every deal.

Well seemed each of them a fair burgess,

To sitten in a guild-hall, on the dais.

Evereach, for the wisdom that he can,

Was shapely for to be an alderman.

For chattels hadde they enough and rent,

And eke their wives would it well assent:

And elles certain they had been to blame.

It is full fair to be y-clep’d madame,

And for to go to vigils all before,

And have a mantle royally y-bore.

A COOK they hadde with them for the nones,

To boil the chickens and the marrow bones,

And powder merchant tart and galingale.

Well could he know a draught of London ale.

He could roast, and stew, and broil, and fry,

Make mortrewes, and well bake a pie.

But great harm was it, as it thoughte me,

That, on his shin a mormal hadde he.

For blanc manger, that made he with the best

A SHIPMAN was there, wonned far by West:

For ought I wot, be was of Dartemouth.

He rode upon a rouncy, as he couth,

All in a gown of falding to the knee.

A dagger hanging by a lace had he

About his neck under his arm adown;

The hot summer had made his hue all brown;

And certainly he was a good fellaw.

Full many a draught of wine he had y-draw

From Bourdeaux-ward, while that the chapmen sleep;

Of nice conscience took he no keep.

If that he fought, and had the higher hand,

By water he sent them home to every land.

But of his craft to reckon well his tides,

His streames and his strandes him besides,

His herberow, his moon, and lodemanage,

There was none such, from Hull unto Carthage

Hardy he was, and wise, I undertake:

With many a tempest had his beard been shake.

He knew well all the havens, as they were,

From Scotland to the Cape of Finisterre,

And every creek in Bretagne and in Spain:

His barge y-cleped was the Magdelain.

With us there was a DOCTOR OF PHYSIC;

In all this worlde was there none him like

To speak of physic, and of surgery:

For he was grounded in astronomy.

He kept his patient a full great deal

In houres by his magic natural.

Well could he fortune the ascendent

Of his images for his patient.

He knew the cause of every malady,

Were it of cold, or hot, or moist, or dry,

And where engender’d, and of what humour.

He was a very perfect practisour

The cause y-know, and of his harm the root,

Anon he gave to the sick man his boot

Full ready had he his apothecaries,

To send his drugges and his lectuaries

For each of them made other for to win

Their friendship was not newe to begin

Well knew he the old Esculapius,

And Dioscorides, and eke Rufus;

Old Hippocras, Hali, and Gallien;

Serapion, Rasis, and Avicen;

Averrois, Damascene, and Constantin;

Bernard, and Gatisden, and Gilbertin.

Of his diet measurable was he,

For it was of no superfluity,

But of great nourishing, and digestible.

His study was but little on the Bible.

In sanguine and in perse he clad was all

Lined with taffeta, and with sendall.

And yet he was but easy of dispense:

He kept that he won in the pestilence.

For gold in physic is a cordial;

Therefore he loved gold in special.

A good WIFE was there OF beside BATH,

But she was somedeal deaf, and that was scath.

Of cloth-making she hadde such an haunt,

She passed them of Ypres, and of Gaunt.

In all the parish wife was there none,

That to the off’ring before her should gon,

And if there did, certain so wroth was she,

That she was out of alle charity

Her coverchiefs were full fine of ground

I durste swear, they weighede ten pound

That on the Sunday were upon her head.

Her hosen weren of fine scarlet red,

Full strait y-tied, and shoes full moist and new

Bold was her face, and fair and red of hue.

She was a worthy woman all her live,

Husbands at the church door had she had five,

Withouten other company in youth;

But thereof needeth not to speak as nouth.

And thrice had she been at Jerusalem;

She hadde passed many a strange stream

At Rome she had been, and at Bologne,

In Galice at Saint James, and at Cologne;

She coude much of wand’rng by the Way.

Gat-toothed was she, soothly for to say.

Upon an ambler easily she sat,

Y-wimpled well, and on her head an hat

As broad as is a buckler or a targe.

A foot-mantle about her hippes large,

And on her feet a pair of spurres sharp.

In fellowship well could she laugh and carp

Of remedies of love she knew perchance

For of that art she coud the olde dance.

A good man there was of religion,

That was a poore PARSON of a town:

But rich he was of holy thought and werk.

He was also a learned man, a clerk,

That Christe’s gospel truly woulde preach.

His parishens devoutly would he teach.

Benign he was, and wonder diligent,

And in adversity full patient:

And such he was y-proved often sithes.

Full loth were him to curse for his tithes,

But rather would he given out of doubt,

Unto his poore parishens about,

Of his off’ring, and eke of his substance.

He could in little thing have suffisance.

Wide was his parish, and houses far asunder,

But he ne left not, for no rain nor thunder,

In sickness and in mischief to visit

The farthest in his parish, much and lit,

Upon his feet, and in his hand a staff.

This noble ensample to his sheep he gaf,

That first he wrought, and afterward he taught.

Out of the gospel he the wordes caught,

And this figure he added yet thereto,

That if gold ruste, what should iron do?

For if a priest be foul, on whom we trust,

No wonder is a lewed man to rust:

And shame it is, if that a priest take keep,

To see a shitten shepherd and clean sheep:

Well ought a priest ensample for to give,

By his own cleanness, how his sheep should live.

He sette not his benefice to hire,

And left his sheep eucumber’d in the mire,

And ran unto London, unto Saint Paul’s,

To seeke him a chantery for souls,

Or with a brotherhood to be withold:

But dwelt at home, and kepte well his fold,

So that the wolf ne made it not miscarry.

He was a shepherd, and no mercenary.

And though he holy were, and virtuous,

He was to sinful men not dispitous

Nor of his speeche dangerous nor dign

But in his teaching discreet and benign.

To drawen folk to heaven, with fairness,

By good ensample, was his business:

But it were any person obstinate,

What so he were of high or low estate,

Him would he snibbe sharply for the nones.

A better priest I trow that nowhere none is.

He waited after no pomp nor reverence,

Nor maked him a spiced conscience,

But Christe’s lore, and his apostles’ twelve,

He taught, and first he follow’d it himselve.

With him there was a PLOUGHMAN, was his brother,

That had y-laid of dung full many a fother.

A true swinker and a good was he,

Living in peace and perfect charity.

God loved he beste with all his heart

At alle times, were it gain or smart,

And then his neighebour right as himselve.

He woulde thresh, and thereto dike, and delve,

For Christe’s sake, for every poore wight,

Withouten hire, if it lay in his might.

His tithes payed he full fair and well,

Both of his proper swink, and his chattel

In a tabard he rode upon a mare.

There was also a Reeve, and a Millere,

A Sompnour, and a Pardoner also,

A Manciple, and myself, there were no mo’.

The MILLER was a stout carle for the nones,

Full big he was of brawn, and eke of bones;

That proved well, for ov’r all where he came,

At wrestling he would bear away the ram.

He was short-shouldered, broad, a thicke gnarr,

There was no door, that he n’old heave off bar,

Or break it at a running with his head.

His beard as any sow or fox was red,

And thereto broad, as though it were a spade.

Upon the cop right of his nose he had head

A wart, and thereon stood a tuft of hairs

Red as the bristles of a sowe’s ears.

His nose-thirles blacke were and wide.

A sword and buckler bare he by his side.

His mouth as wide was as a furnace.

He was a jangler, and a goliardais,

And that was most of sin and harlotries.

Well could he steale corn, and tolle thrice

And yet he had a thumb of gold, pardie.

A white coat and a blue hood weared he

A baggepipe well could he blow and soun’,

And therewithal he brought us out of town.

A gentle MANCIPLE was there of a temple,

Of which achatours mighte take ensample

For to be wise in buying of vitaille.

For whether that he paid, or took by taile,

Algate he waited so in his achate,

That he was aye before in good estate.

Now is not that of God a full fair grace

That such a lewed mannes wit shall pace

The wisdom of an heap of learned men?

Of masters had he more than thries ten,

That were of law expert and curious:

Of which there was a dozen in that house,

Worthy to be stewards of rent and land

Of any lord that is in Engleland,

To make him live by his proper good,

In honour debtless, but if he were wood,

Or live as scarcely as him list desire;

And able for to helpen all a shire

In any case that mighte fall or hap;

And yet this Manciple set their aller cap

The REEVE was a slender choleric man

His beard was shav’d as nigh as ever he can.

His hair was by his eares round y-shorn;

His top was docked like a priest beforn

Full longe were his legges, and full lean

Y-like a staff, there was no calf y-seen

Well could he keep a garner and a bin

There was no auditor could on him win

Well wist he by the drought, and by the rain,

The yielding of his seed and of his grain

His lorde’s sheep, his neat, and his dairy

His swine, his horse, his store, and his poultry,

Were wholly in this Reeve’s governing,

And by his cov’nant gave he reckoning,

Since that his lord was twenty year of age;

There could no man bring him in arrearage

There was no bailiff, herd, nor other hine

That he ne knew his sleight and his covine

They were adrad of him, as of the death

His wonnin was full fair upon an heath

With greene trees y-shadow’d was his place.

He coulde better than his lord purchase

Full rich he was y-stored privily

His lord well could he please subtilly,

To give and lend him of his owen good,

And have a thank, and yet a coat and hood.

In youth he learned had a good mistere

He was a well good wright, a carpentere

This Reeve sate upon a right good stot,

That was all pomel gray, and highte Scot.

A long surcoat of perse upon he had,

And by his side he bare a rusty blade.

Of Norfolk was this Reeve, of which I tell,

Beside a town men clepen Baldeswell,

Tucked he was, as is a friar, about,

And ever rode the hinderest of the rout.

A SOMPNOUR was there with us in that place,

That had a fire-red cherubinnes face,

For sausefleme he was, with eyen narrow.

As hot he was and lecherous as a sparrow,

With scalled browes black, and pilled beard:

Of his visage children were sore afeard.

There n’as quicksilver, litharge, nor brimstone,

Boras, ceruse, nor oil of tartar none,

Nor ointement that woulde cleanse or bite,

That him might helpen of his whelkes white,

Nor of the knobbes sitting on his cheeks.

Well lov’d he garlic, onions, and leeks,

And for to drink strong wine as red as blood.

Then would he speak, and cry as he were wood;

And when that he well drunken had the wine,

Then would he speake no word but Latin.

A fewe termes knew he, two or three,

That he had learned out of some decree;

No wonder is, he heard it all the day.

And eke ye knowen well, how that a jay

Can clepen “Wat,” as well as can the Pope.

But whoso would in other thing him grope

Then had he spent all his philosophy,

Aye, Questio quid juris, would he cry.

He was a gentle harlot and a kind;

A better fellow should a man not find.

He woulde suffer, for a quart of wine,

A good fellow to have his concubine

A twelvemonth, and excuse him at the full.

Full privily a finch eke could he pull.

And if he found owhere a good fellaw,

He woulde teache him to have none awe

In such a case of the archdeacon’s curse;

But if a manne’s soul were in his purse;

For in his purse he should y-punished be.

“Purse is the archedeacon’s hell,” said he.

But well I wot, he lied right indeed:

Of cursing ought each guilty man to dread,

For curse will slay right as assoiling saveth;

And also ’ware him of a significavit.

In danger had he at his owen guise

The younge girles of the diocese,

And knew their counsel, and was of their rede.

A garland had he set upon his head,

As great as it were for an alestake:

A buckler had he made him of a cake.

With him there rode a gentle PARDONERE

Of Ronceval, his friend and his compere,

That straight was comen from the court of Rome.

Full loud he sang, “Come hither, love, to me”

This Sompnour bare to him a stiff burdoun,

Was never trump of half so great a soun.

This Pardoner had hair as yellow as wax,

But smooth it hung, as doth a strike of flax:

By ounces hung his lockes that he had,

And therewith he his shoulders oversprad.

Full thin it lay, by culpons one and one,

But hood for jollity, he weared none,

For it was trussed up in his wallet.

Him thought he rode all of the newe get,

Dishevel, save his cap, he rode all bare.

Such glaring eyen had he, as an hare.

A vernicle had he sew’d upon his cap.

His wallet lay before him in his lap,

Bretful of pardon come from Rome all hot.

A voice he had as small as hath a goat.

No beard had he, nor ever one should have.

As smooth it was as it were new y-shave;

I trow he were a gelding or a mare.

But of his craft, from Berwick unto Ware,

Ne was there such another pardonere.

For in his mail he had a pillowbere,

Which, as he saide, was our Lady’s veil:

He said, he had a gobbet of the sail

That Sainte Peter had, when that he went

Upon the sea, till Jesus Christ him hent.

He had a cross of latoun full of stones,

And in a glass he hadde pigge’s bones.

But with these relics, whenne that he fond

A poore parson dwelling upon lond,

Upon a day he got him more money

Than that the parson got in moneths tway;

And thus with feigned flattering and japes,

He made the parson and the people his apes.

But truely to tellen at the last,

He was in church a noble ecclesiast.

Well could he read a lesson or a story,

But alderbest he sang an offertory:

For well he wiste, when that song was sung,

He muste preach, and well afile his tongue,

To winne silver, as he right well could:

Therefore he sang full merrily and loud.

Now have I told you shortly in a clause

Th’ estate, th’ array, the number, and eke the cause

Why that assembled was this company

In Southwark at this gentle hostelry,

That highte the Tabard, fast by the Bell.

But now is time to you for to tell

How that we baren us that ilke night,

When we were in that hostelry alight.

And after will I tell of our voyage,

And all the remnant of our pilgrimage.

But first I pray you of your courtesy,

That ye arette it not my villainy,

Though that I plainly speak in this mattere.

To tellen you their wordes and their cheer;

Not though I speak their wordes properly.

For this ye knowen all so well as I,

Whoso shall tell a tale after a man,

He must rehearse, as nigh as ever he can,

Every word, if it be in his charge,

All speak he ne’er so rudely and so large;

Or elles he must tell his tale untrue,

Or feigne things, or finde wordes new.

He may not spare, although he were his brother;

He must as well say one word as another.

Christ spake Himself full broad in Holy Writ,

And well ye wot no villainy is it.

Eke Plato saith, whoso that can him read,

The wordes must be cousin to the deed.

Also I pray you to forgive it me,

All have I not set folk in their degree,

Here in this tale, as that they shoulden stand:

My wit is short, ye may well understand.

Great cheere made our Host us every one,

And to the supper set he us anon:

And served us with victual of the best.

Strong was the wine, and well to drink us lest.

A seemly man Our Hoste was withal

For to have been a marshal in an hall.

A large man he was with eyen steep,

A fairer burgess is there none in Cheap:

Bold of his speech, and wise and well y-taught,

And of manhoode lacked him right naught.

Eke thereto was he right a merry man,

And after supper playen he began,

And spake of mirth amonges other things,

When that we hadde made our reckonings;

And saide thus; “Now, lordinges, truly

Ye be to me welcome right heartily:

For by my troth, if that I shall not lie,

I saw not this year such a company

At once in this herberow, am is now.

Fain would I do you mirth, an I wist how.

And of a mirth I am right now bethought.

To do you ease, and it shall coste nought.

Ye go to Canterbury; God you speed,

The blissful Martyr quite you your meed;

And well I wot, as ye go by the way,

Ye shapen you to talken and to play:

For truely comfort nor mirth is none

To ride by the way as dumb as stone:

And therefore would I make you disport,

As I said erst, and do you some comfort.

And if you liketh all by one assent

Now for to standen at my judgement,

And for to worken as I shall you say

To-morrow, when ye riden on the way,

Now by my father’s soule that is dead,

But ye be merry, smiteth off mine head.

Hold up your hands withoute more speech.”

Our counsel was not longe for to seech:

Us thought it was not worth to make it wise,

And granted him withoute more avise,

And bade him say his verdict, as him lest.

“Lordings (quoth he), now hearken for the best;

But take it not, I pray you, in disdain;

This is the point, to speak it plat and plain.

That each of you, to shorten with your way

In this voyage, shall tellen tales tway,

To Canterbury-ward, I mean it so,

And homeward he shall tellen other two,

Of aventures that whilom have befall.

And which of you that bear’th him best of all,

That is to say, that telleth in this case

Tales of best sentence and most solace,

Shall have a supper at your aller cost

Here in this place, sitting by this post,

When that ye come again from Canterbury.

And for to make you the more merry,

I will myselfe gladly with you ride,

Right at mine owen cost, and be your guide.

And whoso will my judgement withsay,

Shall pay for all we spenden by the way.

And if ye vouchesafe that it be so,

Tell me anon withoute wordes mo’,

And I will early shape me therefore.”

This thing was granted, and our oath we swore

With full glad heart, and prayed him also,

That he would vouchesafe for to do so,

And that he woulde be our governour,

And of our tales judge and reportour,

And set a supper at a certain price;

And we will ruled be at his device,

In high and low: and thus by one assent,

We be accorded to his judgement.

And thereupon the wine was fet anon.

We drunken, and to reste went each one,

Withouten any longer tarrying

A-morrow, when the day began to spring,

Up rose our host, and was our aller cock,

And gather’d us together in a flock,

And forth we ridden all a little space,

Unto the watering of Saint Thomas:

And there our host began his horse arrest,

And saide; “Lordes, hearken if you lest.

Ye weet your forword, and I it record.

If even-song and morning-song accord,

Let see now who shall telle the first tale.

As ever may I drinke wine or ale,

Whoso is rebel to my judgement,

Shall pay for all that by the way is spent.

Now draw ye cuts ere that ye farther twin.

He which that hath the shortest shall begin.”

“Sir Knight (quoth he), my master and my lord,

Now draw the cut, for that is mine accord.

Come near (quoth he), my Lady Prioress,

And ye, Sir Clerk, let be your shamefastness,

Nor study not: lay hand to, every man.”

Anon to drawen every wight began,

And shortly for to tellen as it was,

Were it by a venture, or sort, or cas,

The sooth is this, the cut fell to the Knight,

Of which full blithe and glad was every wight;

And tell he must his tale as was reason,

By forword, and by composition,

As ye have heard; what needeth wordes mo’?

And when this good man saw that it was so,

As he that wise was and obedient

To keep his forword by his free assent,

He said; “Sithen I shall begin this game,

Why, welcome be the cut in Godde’s name.

Now let us ride, and hearken what I say.”

And with that word we ridden forth our way;

And he began with right a merry cheer

His tale anon, and said as ye shall hear.

The Miller’s Tale

THE PROLOGUE

When that the Knight had thus his tale told

In all the rout was neither young nor old,

That he not said it was a noble story,

And worthy to be drawen to memory;

And namely the gentles every one.

Our Host then laugh’d and swore, “So may I gon,

This goes aright; unbuckled is the mail;

Let see now who shall tell another tale:

For truely this game is well begun.

Now telleth ye, Sir Monk, if that ye conne,

Somewhat, to quiten with the Knighte’s tale.”

The Miller that fordrunken was all pale,

So that unnethes upon his horse he sat,

He would avalen neither hood nor hat,