4 Primates

Learning Objectives

- Describe how studying nonhuman primates is important in anthropology.

- Compare two ways of categorizing taxa: grades and clades.

- Define different types of traits used to evaluate primate taxa.

- Identify key ways that primates differ from other mammals.

- Distinguish between the major primate taxa using their key characteristics.

- Describe your place in nature by learning your taxonomic classification.

Primates

In the 1970s, a young graduate student primatologist named Barbara Smuts was working under the wing of the renowned primatologist Jane Goodall. They were studying the chimpanzees of Gombe Stream in Tanzania. An adolescent chimpanzee named Goblin was giving Barbara, a petite woman, trouble. Male chimps are hierarchical, and they constantly jockey for political positions in the troop. The young low-ranking males work their way to the top by first intimidating females. Goblin smacked, jabbed, punched, and shoved Barbara daily. Barbara explained what was happening to Goodall, who advised her to just ignore Goblin. One day Goblin decided to grab the raincoat that Barbara was carrying on her back. Raincoats are critical equipment in the rainforest, and so naturally, Barbara resisted. The two began a tug of war over the coat. Then something came over Barbara. She punched Goblin as hard as she could in the face. Goblin collapsed, whimpering on the ground for a moment and then scurried over to the large alpha male, Figgin, for support. Thankfully, instead of attacking Barbara, the powerful chimpanzee reached over and calmly patted Goblin on the head. Goblin never bothered Barbara again.

Examples

Primates are everywhere in Western entertainment: King Kong, Curious George, Zoboomafoo, Grape Ape, Donkey Kong, King Julien, Marcel the capuchin monkey from Friends, and “Monkey” (who is not a monkey) from Kung Fu Panda. Primates also appear in Japanese folklore in tales like the Monkey and Crab. Baboons figure prominently in Egyptian mythology, sometimes being associated with virility and sometimes with Thoth, the god of writing. Among the Classic Maya, howler monkeys are associated with artisans and scribes. The Cercopes were mischievous brothers who were turned into monkeys by Zeus. Typically, the monkeys in these tales are up to no good and receive comeuppance for deviousness and lying. But what are primates exactly, and how can they shed light on what it means to be human?

Humans have much in common with other animals, especially apes and monkeys. We share tools, reasoning, complex sociality, emotion, reciprocity, and even culture, according to some definitions of the term. We also share susceptibility to many of the same zoonotic diseases like polio, measles, Ebola, and COVID-19. Because humans share so much in common socially and biologically with apes, monkeys, and similar species, we are all classified as Primates. That is, we are all in the Primate Order. Primatology is a sub-discipline of biological anthropology that focuses on primate behavior, biology, and conservation.

In antiquity, many people subscribed to the idea of the Great Chain of Being, which was a classification system that included animals, plants, rocks, and divine beings (Figure 4.1). These were each ranked according to their moral perfection. God is at the top of the chain and dirt at the bottom. The closer to God, the more godly. The further away from God, the less godly. Angels were near the top, and humans below them. This system was of course, entirely subjective, meaning based on personal preference.

In defiance of the the Great Chain of Being, Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) decided to categorize all living things based on their physical similarities. In his Systema Naturae, he outlined a system of naming as well. Most of us are familiar with the genus and species system of the taxonomy called the binomial system, meaning two-name system. Our genus is “Homo” and our species is “sapiens”, meaning “wise man” or “wise person.” Unlike the Great Chain of Being, Linnaeus’ system was not based on ranking species according to better or worse, but rather on their physical similarities. The categories of the classification become increasingly more narrow, like nested dolls. The broadest category in the kingdom, as in the animal and plant kingdoms. The other categories are phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. (The category of the domain was added before kingdom in recent years). Primates is an Order in the taxonomic system. There are about 300 species of primates most of which live in tropical climates making it one of the largest groups of mammals in the world.

Linnaeus’ naming system which he created in the 18th century is still in use today. But now, we add the additional information on genetics to the basic system of physical comparison. Genetic analysis is critical because some species that look very much alike, aren’t that closely related, and can yield surprising and counter-intuitive results. For instance, New World Monkeys and Old World Monkeys look alike superficially, but Old World Monkeys are more closely related to apes than to New World Monkeys. In the “Code of Life” chapter, we learned about SNPs or changes in a single letter in DNA. SNPs and other types of mutations can be compared to estimate how closely related species are. A system that categories based only on physical characteristics is called a grade. Grade group by physical similarity, but not necessarily genetic and evolutionary relationships. A clade, however, is based on relatedness between species based on similarity and genetics. Categorizing all living species is of course a daunting task, and no one person can hope to classify all of them as Linnaeus attempted to do. The Catalogue of Life is an online database of the world’s known species, containing 1.64 million species of the estimated 1.9 million species in the world.

Stephanie Etting in“Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, explains two types of traits that primatologists are interested in. When evaluating relationships between species, we use key traits that allow us to determine which species are most closely related to one another. Traits can be either ancestral or derived. Ancestral traits are those that a taxon has because it has inherited the trait from a distant ancestor. For example, all primates have body hair because we are mammals and all mammals share an ancestor hundreds of millions of years ago that had body hair. This trait has been passed down to all mammals from a shared ancestor, so all mammals alive today have body hair. derived traits are those that have been more recently altered. This type of trait is most useful when we are trying to distinguish one group from another because derived traits tell us which taxa are more closely related to each other. For example, humans walk on two legs. The many adaptations that humans possess that allow us to move in this way evolved after humans split from the Genus Pan. This means that when we find fossil taxa that share derived traits for walking on two legs, we can conclude that they are likely more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees and bonobos.

There are two other types of traits that will be relevant to our discussions here: generalized and specialized traits. Generalized traits are those characteristics that are useful for a wide range of things. Having opposable thumbs that go in a different direction than the rest of your fingers is a very useful, generalized trait. You can hold a pen, grab a branch, peel a banana, or text your friends all thanks to your opposable thumbs! Specialized traits are those that have been modified for a specific purpose. These traits may not have a wide range of uses, but they will be very efficient at their job. Hooves in horses are a good example of a specialized trait: they allow horses to run quickly on the ground on all fours. You can think of generalized traits as a Swiss Army knife, useful for a wide range of tasks but not particularly good at any one of them. That is, if you’re in a bind, then a Swiss Army knife can be very useful to cut a rope or fix a loose screw, but if you were going to build furniture or fix a kitchen sink, then you’d want specialized tools for the job. As we will see, most primate traits tend to be generalized.

What is a Primate?

You are likely familiar with the Class called Mammalia. You know a mammal when you see one, but what are the specific traits? Mammals share several features. Mammal characteristics include bearing live young, nursing their young, having a vertebral column, being warm-blooded, and having fur. Primates are a group of species within the Class Mammalia, and so they share all the features of mammals, plus the features of primates. So, they share several features in common that are absent in other mammals. Some of these common tendencies are morphological (related to form) and others revolve around life history (features having to do with the timing and duration of life events like growth, reproduction, and aging). The primate traits represent a collection of traits. That is, a primate species will have several, but possibly not all these traits.

Primate trends:

- Relatively long period of immaturity compared to other mammals marked by learning the social and physical environment

- Late sexual maturity and long lives

- Few offspring

- High degree of parental investment in offspring

- Complex sociality (grooming, alliances, conflict)

- Grasping hands (some have opposable thumbs) and five fingers

- Stereoscopic vision (visual fields overlap for 3D vision)

- Post-orbital bar

- Relatively large brain to body size

- Reduced sense of smell, short snouts

- Nails not claws and sensitive finger pads

- Primates Features

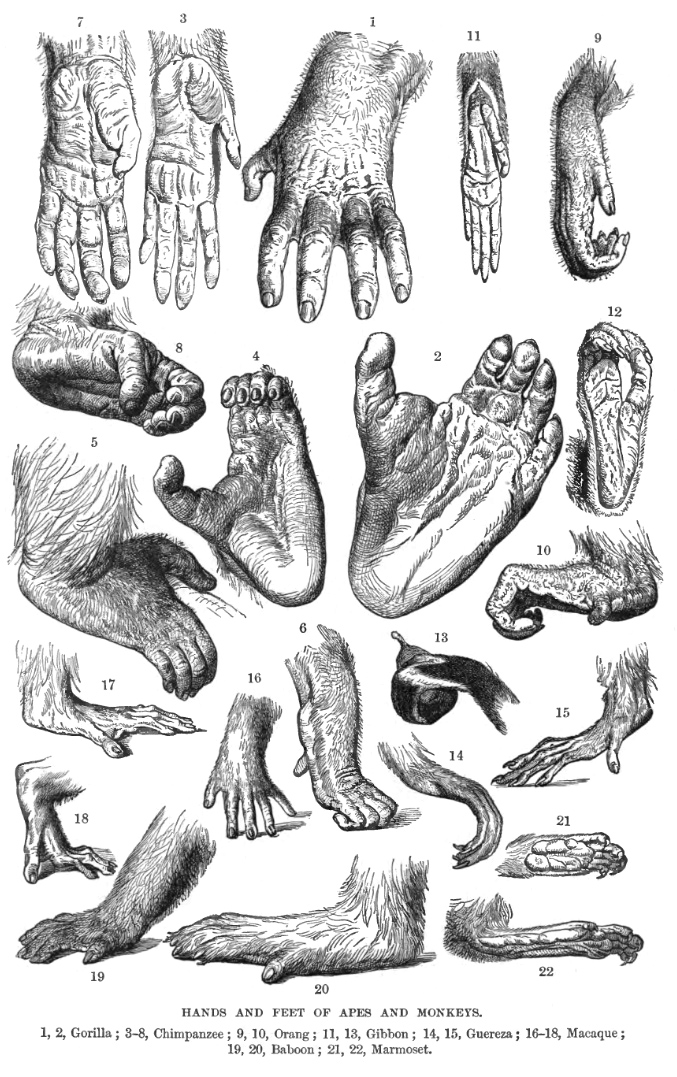

Primates are often arboreal, but not always, meaning they often spend time in trees. The primate hand and foot is adapted to this complex environment. The primate hand has five fingers (but the spider monkey is an exception with no thumb) and is capable of grasping (Figure 4.2). Having five fingers is called pentadactyly and is an ancestral trait. Some primates like apes and Old World monkeys have true opposable thumbs, meaning the thumb can be oriented in opposition to the other digits. Grasping hands allows primates to manipulate their environment and for some, make and use tools. Some primates, especially those that are arboreal, living in trees, also have grasping feet. Other species like horses, who basically walk on a single toe, are more terrestrial (ground-dwelling). This horse hoof configuration is more suited to speed than to navigating a rainforest canopy. Primates also tend to have flat nails instead of claws on hooves which allows us to manipulate objects easily. Primates also have an expanded capacity for touch, with sensitive pads especially on fingers. This touch allows primates to explore their environments and also be adept at social grooming.

Primates tend to live in social groups. Social grooming is especially important for many primates. Baboons who groom each other regularly, are more likely to come to each other’s aid in a crisis. Thus, social grooming is a form of reciprocity (exchanging favors). There are exceptions, for example, orangutans lead mostly solitary lives.

Primates tend to have a relatively poor smell, but keen eyesight. Mammals in general have about the same number of genes that influence the sense of smell. In primates, many of these genes are no longer functioning. The genes are either turned off by regulator genes or are deactivated by mutations. This is why we train other animals like dogs and rats to sniff out drugs, explosives, and even diseases. Rats, for instance, have been trained to sniff out land mines in Cambodia, of which there are 6 million. (One rat named Magawa was so good at finding land mines that he was given a gold medal by the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals).

Stephanie Etting in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, explains the energy expenditure of primate vision. The primate visual system uses a lot of energy, so primates have compensated by cutting back on other sensory systems, particularly our sense of smell. Compared to other mammals, primates have reduced snouts, another derived trait that appears even in the earliest primate ancestors. There is variation across primate taxa in how much snouts are reduced. Those with a better sense of smell usually have poorer vision than those with a relatively dull sense of smell. The reason for this is that all organisms have a limited amount of energy to spend on running our bodies, so we make evolutionary trade-offs, as energy spent on one trait cuts back on energy spent on another. So primates with better vision are spending more energy on vision and thus have a poorer smell (and shorter snout), and those who spend less energy on vision will have a better sense of smell (and a longer snout).

While primate smell isn’t extraordinary, primates instead are the “most visually adapted order of animals” (Heesy 2009). All primates have fields of vision that overlap, which allows for keener three-dimensional depth perception called stereoscopic vision or stereopsis. With stereoscopic vision, the fields of view overlap, and the two different images seen by each eye are combined in the brain to form a three-dimensional image. Stephanie Etting in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, explains primate vision. So if you cover one eye with your hand, you can still see most of the room with your other one. This also means that we cannot see on the sides or behind us as well as some other animals can. In order to protect the sides of the eyes from the muscles we use for chewing, all primates have at least a postorbital bar, a bony ring around the outside of the eye (Figure 4.3). Because many primates are arboreal, it has been suggested that keen eyesight is critical for judging distance and depth of tree branches. Others argue that this type of vision developed in relation to the predation of insects. A binocular field of vision is common in predators who need to judge distances (Figure 4.4). Non-overlapping fields of view are more common in prey animals, who need a wider field of vision to spot predators.

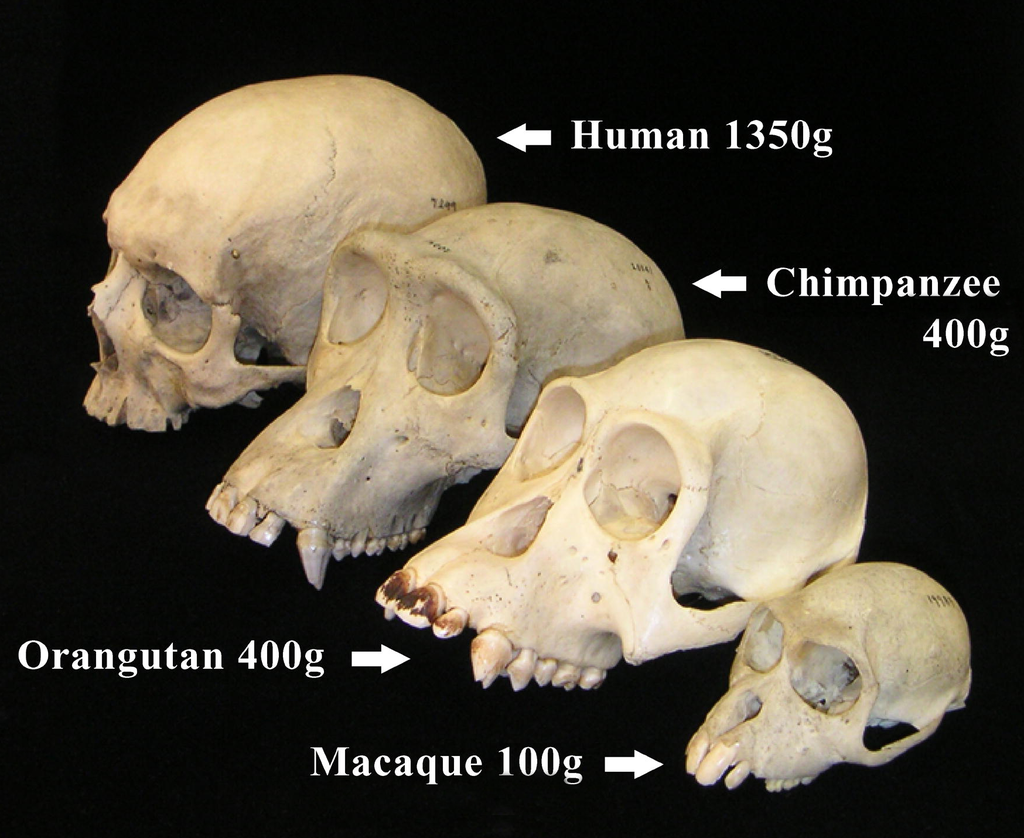

Primates also have larger than expected brains for their body size—about two times as large as they “should” be (Figure 4.5). This is called the encephalization quotient. In addition, brain areas associated with vision, memory, thought, and association are increased in primates. Primates proportionally devote more brain to the neocortex than any other animal. The neocortex is the seat of cognition, language, memory, abstractions, anthropology, and so forth. Indeed, primates can solve complex problems and use tools. The neocortex is also folded in on itself to create more surface area for basically more brains. If you unfolded the human cortex, it would be about the size of an area rug.

Stephanie Etting in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, discusses possible reasons for the expanded primate neocortex. It has been proposed that the more complex neocortex of primates is related to diet, with fruit-eating primates having larger relative brain sizes than leaf-eating primates due to the more challenging cognitive demands required to find and process fruits (Clutton-Brock and Harvey 1980). An alternative hypothesis argues that larger brain size is necessary for navigating the complexities of primate social life, with larger brains occurring in species who live in bigger, more complex groups relative to those living in pairs or solitarily (Dunbar 1998). Primates use flexible thinking not only to forage for patchily distributed food and solve physical problems but also to negotiate group dynamics. Primates often live in socially complex groups and must form and manage social ties (called affiliation) and avoid conflict (called agonism). Chimpanzee males often work together and cooperate to dominate other chimpanzees. Another socially complex aspect of primate life is dispersal. Dispersal occurs when males or females move out of their natal group at maturity and join another group. As with human exogamy, moving out of one’s natal group can be a risky endeavor, requiring skillful negotiation. Not so different from humans, the social lives of primates can be stressful. Robert Sapolsky has studied the stressful effects of baboon social life. He spent 30 years darting African baboons to check their hormone levels, a measure of how much stress they experience. Sapolsky learned that baboons, especially low-ranking baboons and baboons who lack social connections have high stress levels and poor health. As Sapolsky puts it “Primates are super smart and organized just enough to devote their free time to being miserable to each other and stressing each other out” (Shwartz 2007).

As far as life history traits, primates do not subscribe to “live fast, die young.” Rather, primate infants take a long time to develop, and a strong mother-infant bond develops. Most primates give birth to a single offspring and offspring often receive extensive care called “parental investment” from the mother. In a few cases, males will provide some support as well. During this long period of dependency, the infant learns appropriate behavior and how to solve problems. Orangutan juvenile period can last up to seven years and is one of the slowest reproducers of all (Figure 4.6). But of course, humans also stand out in this arena with an impressively long period of juvenile dependence. Primates also tend to be long-lived with humans and the great apes living the longest.

While non-human primates once lived in North America, including what is today New Mexico, today they live is Asia and Africa typically in tropical and subtropical environments. Primates can live in a range of environments to swampy areas, semi-aridic areas, rocky terrain, grasslands, and rainforests. Japanese macaques or snow monkeys live in Japan in mountainous and hilly areas. No other primate, apart from humans, lives so far north. Monkeys are widespread living in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. Apes live in Africa and Asia and lemurs live exclusively on Madagascar. Other primates related to lemurs live in Asia and on the African mainland.

Exercises

Primate Groups: The Streps and the Haps

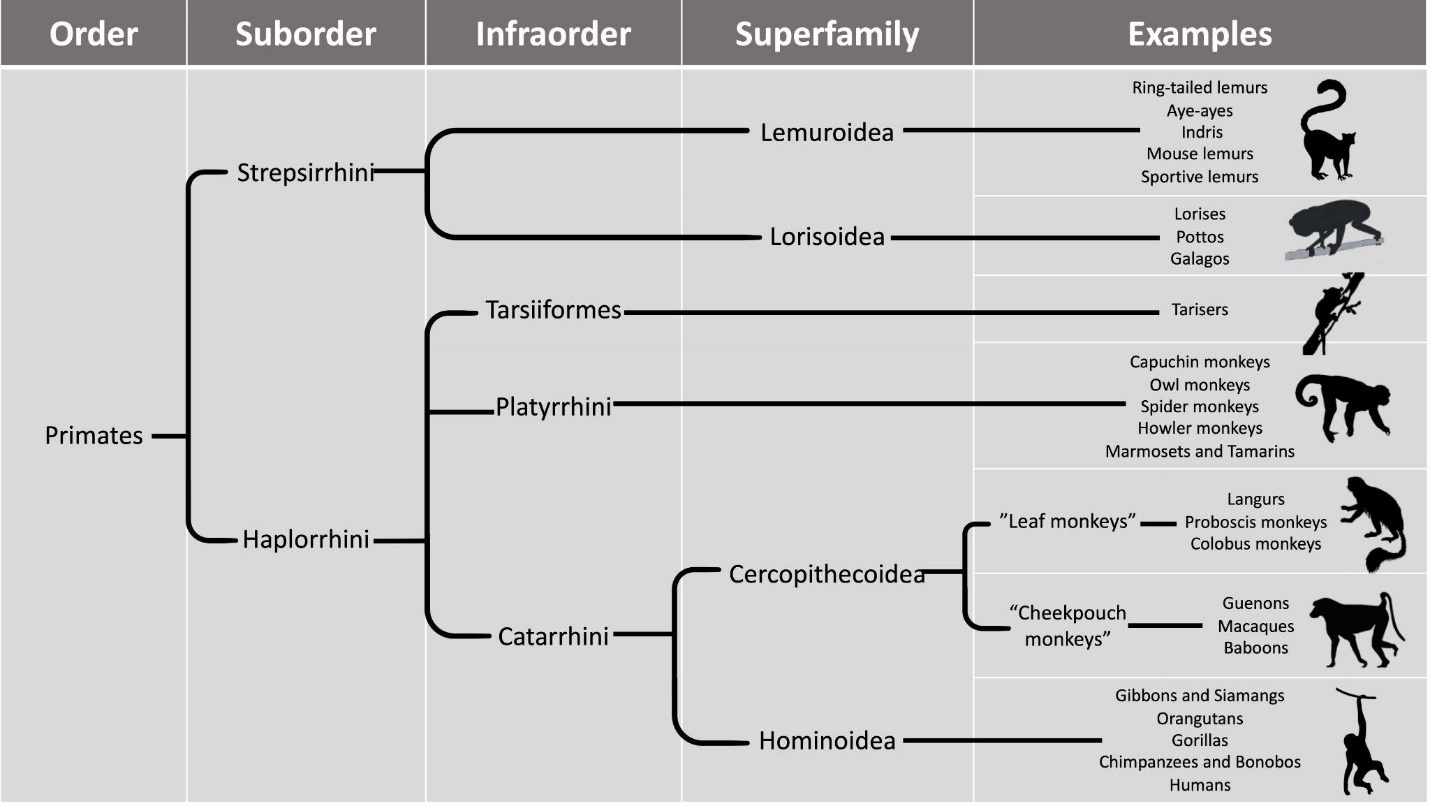

There are several groupings within the Primate order, but there are two main groups (suborders) within the primate order the strepsirrhines and the haplorrhines or the “streps” and the “haps” (Figure 4.7). Each group contains species that are closely related. The suborders are further divided according to genetic similarity. For instance, strepsirrhines are further divided into Lemuroidea and Lorisoidea. Previously, primates were grouped according to physical similarity only, much like Linnaeus’ classification system. Today, the groups are based on genetic similarity and evolutionary relatedness.

The Streps

Strepsirrhines are thought to have branched off from the primate line around 80 million years ago and are therefore different in many respects from other primates. That is, they retain features of earlier fossil primates or ancestral traits. They tend to be smaller, more often nocturnal, better smellers, less social, and more insectivorous (insect eaters) than other primates. Strepsirrhines include lorises, galagos, pottos, and lemurs.

Strepsirrhines have the following features in common:

- wet-nosed (rhinarium)

- tooth comb (modified incisors and canines for grooming)

- tapetum lucidum (eye shine)

- grooming claw on the second toe

- small bodies

- reliance on scent

Stephanie Etting explains strepsirrhine senses in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. Compared to haplorrhines, strepsirrhines rely more on nonvisual senses. Strepsirrhines get their name because they have wet noses (rhinariums) like cats and dogs, a trait that, along with a longer snout, reflects strepsirrhines’ greater reliance on olfaction relative to haplorrhines. Many strepsirrhines use scent marking, including rubbing scent glands or urine on objects in the environment to communicate with others. Additionally, many strepsirrhines have mobile ears that they use to locate insect prey and predators. While strepsirrhines have a better sense of smell than haplorrhines, their visual adaptations are more ancestral. Strepsirrhines have less convergent eyes than haplorrhines and therefore all have postorbital bars, whereas haplorrhines have full postorbital closure. All strepsirrhines have a tapetum lucidum, a reflective layer at the back of the eye that reflects light and thereby enhances the ability to see in low-light conditions. It is the same layer that causes your dog or cat to have “yellow eye” when you take photos of them with the flash on. This is a trait thought to be ancestral among mammals as a whole.

Exercises

Strepsirrhines also differ from haplorrhines in some aspects of their ecology and behavior as Stephanie Etting explains strepsirrhine senses in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates.” The majority of strepsirrhines are solitary, traveling alone to search for food; a few taxa are more social. Most strepsirrhines are also nocturnal and arboreal. Strepsirrhines are, on average, smaller than haplorrhines, and so many of them have a diet consisting of insects and fruit, with few taxa eating primarily leaves. Lastly, most strepsirrhines are good at leaping, with several taxa specialized for vertical clinging and leaping. In fact, among primates, all but one of the vertical clinger leapers belong to the Suborder Strepsirrhini. Strepsirrhines can be found all across Asia, Africa, and on the island of Madagascar (Figure 5.18). The Suborder Strepsirrhini is divided into two groups: (1) the lemurs of Madagascar and (2) the lorises, pottos, and galagos of Africa and Asia. By molecular estimates, these two groups split about 65 million years ago (Pozzi et al. 2014).

Lemurs

Let’s look at some streps a little closer. Lemurs only live on the island of Madagascar (where there are no monkeys) and have diversified into more than 30 species, all of which are endangered. Most lemurs are arboreal, or tree-dwelling, but others are terrestrial, living on the ground. Arboreal lemurs move about mainly by clinging and leaping. Sifakas, a type of lemur, leap off a tree, turn their bodies in mid-air, and then land on another tree. Because their bodies are adapted for leaping, lemur legs are long in comparison to their arms. While ideal for moving among branches, moving on the ground results in an odd balletic leaping movement. Lemurs are quite diverse, some being leaf-eaters (folivores), others are fruit-eaters (frugivores), and others eat insects (insectivores). Some lemurs have specialized dentition known as a tooth comb for self-grooming (Figure 4.9). The aye-aye is a well-known lemur with a large brain and a specialized extra-long middle finger for foraging for grubs in trees. The aye-ayes use their special finger to tap on trees to identify grubs, kind of like a woodpecker. It uses this same finger to fish out the grub. Unfortunately, this very unusual species is threatened. According to the Lemur Conservation Foundation, some Madagascar villagers consider the aye-aye to be a harbinger of death and illness and will kill the aye-aye to prevent bad omens.

Some lemurs are nocturnal while others are diurnal, active during the day. The body size and diet of lemurs vary considerably, ranging from the tiny pygmy mouse lemur to the 20-pound Indri. Some lemurs have interesting and unexpected behaviors. For example, black ruffed lemurs bite into poisonous millipedes, which combined with their saliva can act as an insect repellent (Birkinshaw 1999). Primatologist Louise Peckre and colleagues (2018) found that lemurs rub the millipedes on their anuses to prevent threadworms from laying eggs on their anal regions. These behaviors are known as “self-anointing.”

Lorises are omnivorous, solitary, and arboreal, meaning they live in trees. The Javan slow loris is now critically endangered due to the illegal pet trade, use in traditional medicines, and deforestation. The slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus) is the only venomous primate. Although owning slow lorises as pets is illegal, they have appeared as pets in popular Youtube videos. According to primatologist Anna Nekaris (2013), when kept as pets, loris teeth are painfully removed, and they are exposed to bright lights which can blind them because they are nocturnal. Nekaris argues that social media, on the whole, is harming rather than helping the slow loris and advocates for Youtube to have a way for people to police animal cruelty videos. “Bushbabies” also called galagos are another well-known species of loris (Figure 4.10).

Lorises, Pottos, Galagos

Stephanie Etting explains describes lorises, pottos, and galagos in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. Unlike the lemurs of Madagascar, lorises, pottos, and galagos live in areas where they share their environments with monkeys and apes, who often eat similar foods. Lorises live across South and Southeast Asia, while pottos and galagos live across Central Africa. Because of competition with larger-bodied monkeys and apes, mainland strepsirrhines are more restricted in the niches they can fill in their environments and so are less diverse than the lemurs.

The strepsirrhines of Africa and Asia are all nocturnal and solitary, with little variation in body size and diet. For the most part, the diet of lorises, pottos, and galagos consists of fruits and insects. A couple of species eat more gum, but overall the diet of this group is narrow when compared to the Malagasy lemurs. Lorises and pottos are known for being slow, quadrupedal climbers, moving quietly through the forests to avoid being detected by predators. These strepsirrhines have developed additional defenses against predators. Lorises, for example, eat a lot of caterpillars, which makes their saliva slightly toxic. Loris mothers bathe their young in this toxic saliva, making the babies unappealing to predators. In comparison to the slow-moving lorises and pottos, galagos are active quadrupedal runners and leapers that scurry about the forests at night. Galagos make distinctive calls that sound like a baby crying, which has led to their nickname “bushbabies.”

Haplorrhines

The Haplorhines consist of tarsiers, monkeys, apes, and humans. These species do not always look similar, but again genetics indicate they are more closely related to each other than they are to the Strepsirhines. The haplorrhines (or dry noses) have different features compared to the strepsirrhines. Haplorrhines have shorter snouts, a dry nose, and better vision than Strepsirhines. They have a full post-orbital closure around their eyes to protect them. In addition, haplorhines have trichromatic vision, meaning they see three primary colors. A depression in the back of the retina called a fovea allows haplorrhines to view things closely and in detail. Being mostly diurnal (active during the day, haplorrhines lack tapetum lucidum or eye shine. Haplorrhines tend to be much bigger than Strepsirhines and have greater parental care, a longer period of development, and longer lives. Along with relatively big bodies, haplorrhines tend to have larger brains as well. Finally, haplorrhines tend to live in larger social groups than strepsirrhines, with some exceptions. Instead of grooming claws, haplorhines tend to form bonds using social grooming.

- No rhinarium (no wet nose)

- reduced reliance on smell and shorter snouts

- better vision and fovea for keen detailed closeup eyesight

- No tapetum lucidum (no eye shine)

- Bigger body

- Bigger brain-to-body size

- longer gestation

- more parental care

- more social grooming with hands

- Most are diurnal (active during the day)

Tarsiers

Within the haplorrhines, there are three groups (infraorders). Remember, these groups are based on how closely related they are based on genetics (Figure 4.11). These are the tarsiers, platyrrhines (New World Monkeys), and catarrhines (Old World Monkeys, apes, and humans). Tarsiers are in a group by themselves and were once thought to be more closely related to pottos, galagos, lemurs, and lorises. Their former classification was based on similar features, like noctural adaptation, grooming claws, clinging and leaping. This grouping is a grade, not a clade. Genetics and derived traits more similar to haplorrhines (e.g., no rhinarium or tapetum lucidum) have placed tarsiers in with the latter suborder. Tarsiers are solitary primates that live in Southeast Asia. They are nocturnal insectivores and eat no plant matter. Despite being nocturnal, they have no tapetum lucidum (eye shine). Tarsiers instead have gigantic eyes to see at night, each of which is larger than their brain. Tarsiers are small and move by vertical clinging and leaping like a Strepsirhine and have an enlarged tarsal or foot bone as an adaptation to leaping from tree to tree.

Stephanie Etting outlines main differences between the strepsirrhines and haplorrhines in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. The Haplorrhini differ from the Strepsirrhini in their ecology and behavior as well. Haplorrhines are generally larger than strepsirrhines, and they tend to be folivorous and frugivorous. This dietary difference is reflected in the teeth of haplorrhines, which are broader with more surface area for chewing. The larger body size of this taxon also influences locomotion. Only one haplorrhine is a vertical clinger and leaper. Most members of this suborder are quadrupedal, with one subgroup specialized for brachiation. A few haplorrhine taxa are sexually monomorphic, meaning males and females are the same size, but many members of this group show moderate to high sexual dimorphism in body size and canine size. Haplorrhines also differ in social behavior. All but two haplorrhines live in groups, which is very different from the primarily solitary strepsirrhines. Differences between the two suborders are summarized in Figure 4.12.

|

|

||

|

|

Suborder Strepsirrhini |

Suborder Haplorrhini |

|

Sensory adaptations |

Rhinarium Longer snout Eyes less convergent Postorbital bar Tapetum lucidum Mobile ears |

No rhinarium Short snout Eyes more convergent Postorbital plate No tapetum lucidum Many are trichromatic Fovea |

|

Dietary differences |

Mostly insectivores and frugivores, few folivores |

Few insectivores, mostly frugivores and folivores |

|

Activity patterns and Ecology |

Mostly nocturnal, few diurnal or cathemeral Almost entirely arboreal |

Only two are nocturnal, rest are diurnal Many arboreal taxa, also many terrestrial taxa |

|

Social groupings |

Mostly solitary, some pairs, small to large groups |

Only two are solitary, all others live in pairs, small to very large groups |

|

Sexual dimorphism |

Minimal to none |

Few taxa have little/none, many taxa show moderate to high dimorphism |

New World Monkeys: The Platyrrhines

The other two groups (infraorders) within the haplorrhines are the platyrrhines and the catarrhines (plats and cats!). Platyrrhine means flat nose and catarrhine means narrow nose. The platyrrhines are the New World Monkeys from Central and South America (Figures 4.13-4.16). The catarrhines include Old World monkeys, apes, and humans. New World monkeys live only in Central and tropical South America and are the only primates (besides human) who live there. These monkeys have been separated from Old World monkeys for about 35 million years. These monkeys have flat noses with wide-spaced, usually round, nostrils. New World monkeys are mainly arboreal and most are diurnal, active during the day and sleeping at night. Some New World monkeys, like howler and spider monkeys, also have prehensile tails, meaning they can be used to grasp tree branches. Old World monkeys of Africa and Asia do not have prehensile tails. All platyrrhines are arboreal, living in trees.

Some species of New World monkeys rely on tree sap and these are called gumivores. Others, like the spider monkey, rely largely on fruit and are frugivores. Howler monkeys are the only New World monkey to rely heavily on leaves and are folivores.

Catarrhines

Stephanie Etting outlines some main features of catarrhines in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. Relative to other haplorrhine infraorders, catarrhines are distinguished by several characteristics. Catarrhines have a distinctive nose shape, with teardrop-shaped nostrils that are close together and point downward and one fewer premolar than most other primates, giving us a dental formula of 2:1:2:3. On average, catarrhines are the largest and most sexually dimorphic of all primates. Gorillas are the largest living primates, with males weighing up to 220 kg. The most sexually dimorphic of all primates are mandrills. Mandrill males not only have much more vibrant coloration than mandrill females but also have larger canines and can weigh up to three times more (Setchell et al. 2001). The larger body size of catarrhines is related to the more terrestrial lifestyle of many members of this infraorder. In fact, the most terrestrial of living primates can be found in this group. Among all primates, vision is the most developed in catarrhines. Catarrhines independently evolved the same adaptation as howler monkeys in having each X chromosome with genes to distinguish both reds and yellows, so all male and female catarrhines are trichromatic, which is useful for these diurnal primates.

Superfamily: (Old World Monkeys) Cercopithecoidea

Old World monkeys are more closely related to apes and humans than they are to New World Monkeys (platyrrhines). The approximately 75 species of Cercopithecoidea (Old World monkeys” that live in Africa and South Asia and are typically larger than their Platyrrhine (New World) counterparts (Figures 4.17-4.20). They have more closely spaced downward-facing nostrils, and their noses are less flat than New World monkeys. Another distinguishing feature of Old World monkeys are their bilophdont molars. These molars are square with four cusps that are connected by ridges. So, if you ever have the opportunity to look inside a monkey’s mouth, you’ll be able to tell if it’s an Old World monkey (cercopithecoid) or not. All Old World monkey species live in social groups. All cercopithecoids also have ischial callosities, thickened skin that act as seat pads for sitting on rough surfaces like tree branches or the ground.

Stephanie Etting outlines two branches of Cercopithecoidea in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. Cercopithecoidea is split into two groups, the leaf monkeys and the cheek-pouch monkeys. Both groups coexist in Asia and Africa; however, the majority of leaf monkey species live in Asia with only a few taxa in Africa. In contrast, only one genus of cheek-pouch monkey lives in Asia, and all the rest of them in Africa. As you can probably guess based on their names, the two groups differ in terms of diet. Leaf monkeys are primarily folivores, with some species eating a significant amount of seeds. Cheek-pouch monkeys tend to be more frugivorous or omnivorous, with one taxon, geladas, eating primarily grasses. The two groups also differ in some other interesting ways. Leaf monkeys tend to produce infants with natal coats—infants whose fur is a completely different color from their parents. Leaf monkeys are also known for having odd noses, and so they are sometimes called “odd-nosed monkeys.” Cheek-pouch monkeys are able to pack food into their cheek pouches, thus allowing them to move to a location safe from predators or aggressive individuals of their own species where they can eat in peace.

Langurs are a well-known leaf monkey species. Several species of langurs are endangered or critically endangered like the grey-shanked douc (Pygathrix cinerea) of Vietnam. This Old World monkey is losing ground to agriculture, logging, hunting, and the pet trade. At least four other langur species are also critically endangered. Another well-known leaf monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is the proboscis monkey of Southeast Asia. The males and females of this species are sexually dimorphic. Sexual dimorphism refers to differences in “secondary sexual characteristics” like size, weight, coloration, and behavior. Males have much larger noses than females (sexual dimorphism), which can be up to 10 cm. These unusual monkeys are now endangered.

Exercises

Superfamily: Hominoidea: Apes

All apes live in either in Africa or southern Asia. Compared to monkeys, apes are large-bodied, large-brained, and most are terrestrially adapted. Also, unlike monkeys, apes do not have tails. The ape shoulder has greater rotation than monkeys allowing them to hang and swing from branches. All apes are diurnal, and active during the day. Apes are more closely related to Old World monkeys than New World monkeys. Apes are divided into the lesser apes or gibbons and the great apes. The great apes, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans, are the largest of all primates. Gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos live in tropical Africa, while the orangutan lives in southeast Asia on only two islands of Indonesia. Most are primarily herbivorous eating leaves or fruits, and to a lesser extent in some species insects and meat. The African great apes live in complex social groups, while the orangutan is mainly solitary. All great apes are endangered.

Hominoids are adapted to brachiation, swinging arm over arm. To accomdiae this form of locomotion, hominoids have larger arms than legs and a less flexible lower back to promote control. Stephanie Etting explains other adaptations to brachiation in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” in Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. The torso, shoulders, and arms of hominoids have evolved to increase range of motion and flexibility. The clavicle, or collar bone, is longer to stabilize the shoulder joint out to the side, thus enabling us to rotate our arms 360 degrees. Hominoid rib cages are wider side to side and shallower front to back than those of cercopithecoids and we do not have tails, as tails are useful for balance when running on all fours but generally not useful while swinging.

Stephanie Etting summarizes life history traits of hominoids. Apes and humans also differ from other primates in behavior and life history characteristics. Hominoids all seem to show some degree of female dispersal at sexual maturity but, it is more common that males leave. Some apes show males dispersing in addition to females, but the hominoid tendency for female dispersal is a bit unusual among primates. Our superfamily is also characterized by the most extended life histories of all primates. All members of this group take a long time to grow and reproduce much less frequently compared to cercopithecoids. The slow pace of this life history is likely related to why hominoids have decreased in diversity since they first evolved.

Gibbons and Siamangs

The lesser apes live in Southeast Asia and are smaller than other apes with smaller brains. Lesser apes are mainly arboreal and have a particular type of locomotion called brachiation. Brachiation involves swinging from branch to branch by the arms, including a phase of free-flight. Lesser apes resemble monkeys, but they lack tails. Lesser apes often live in socially monogamous pairs, but males do not typically provide much in the way of parental investment. The lesser apes are various types of gibbons and siamangs (Figure 4.21).

Exercises

Gorillas

Gorillas are the largest of the apes and live exclusively in Africa. The gorilla lives in social groups called troops consisting of 10-20 gorillas including the silverback male, adult females, and their children. The silverback male, named for the silvery hair that develops on his back and rump around 12 or 13 years of age, is the only breeding male in the group and he protects his reproductive access to females in the group. As in humans, this is referred to as polygyny. Males (350 lbs.) tend to be much larger than females (155 lbs.), exhibiting a high degree of sexual dimorphism or difference in form between males and females.

Gorillas have a mainly vegan diet of leaves sometimes supplemented with ants or fruit, and spend most of their waking hours eating. Gorillas locomote by knuckle-walking, that is, they walk on the knuckles of their hands rather than on their palms. Gorillas are mostly terrestrial, typically building nests on the ground for sleeping. Infants are helpless and require a high degree of parental investment from the mothers. Newborn gorillas nurse at least once per hour. Silverbacks will protect offspring from aggression and socialize juveniles. The lifespan of a gorilla in the wild is between 35 and 40 years.

Exercises

There are two general varieties of gorilla, the western gorilla, and the eastern gorilla, all of which are critically endangered (Figure 4.22). “Critically endangered” is the last survival status above extinct. Mountain gorillas are a well-known eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) living in central Africa in the Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda in the vicinity of the Virunga volcanoes. Only about 1,000 of these mountain gorillas are left. Threats to mountain gorillas include poaching, political unrest, and loss of habitat due to human expansion. Fortunately, mountain gorilla numbers of Virunga are increasing since an all-time low in the 1980s of 254. The lowland eastern gorilla population, however, declined 70% in the last 20 years. There are no mountain gorillas in captivity. Previous attempts at captivity have resulted in death.

Orangutans

Orangutans live exclusively in Indonesia on Sumatra and Borneo and are the only great ape to live outside Africa (Figure 4.23). Orangutans differ from other great apes in that they are mainly solitary, and live high in the rainforest canopy. Orangutans live mainly on fruits and leaves, and like all great apes build nests. They’ve even been known to fashion leaf umbrellas to protect themselves from rain. Orangutans make a unique kissing sound called a “kiss squeak” when they are agitated. Like gorillas, orangutans have sexual dimorphism, with males being twice the size of females. Stephanie Etting explains orangutan sexual dimorphism in “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” of Exploration and Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology. They are highly sexually dimorphic, with fully developed, “flanged” males being approximately twice the size of females. These males have large throat sacs; long, shaggy coats; and cheek flanges. The skulls of male orangutans often feature a sagittal crest, which is believed to function as additional attachment area for chewing muscles as well as a trait used in sexual competition (Balolia, Soligo, and Wood 2017). An unusual feature of orangutan biology is male bimaturism. Male orangutans are known to delay maturation until one of the more dominant, flanged males disappears. The males that delay maturation are called “unflanged” males, and they can remain in this state for their entire life. Unflanged males resemble females in their size and appearance and will sneak copulations with females while avoiding the bigger, flanged males. Flanged and unflanged male orangutans represent alternative reproductive strategies, both of which successfully produce offspring (Utami et al. 2002).

Like other apes, orangutan infants require a great deal of maternal care, staying with their mothers for six years or more. Orangutans are particularly susceptible to extinction because they reproduce only every 7 or 8 years, the longest birth spacing among mammals. In the 1970s, Biruté Galdikas famously studied Bornean orangutans in the wild and tried to reintroduce captive pet infants and juvenile orangutans back into the wild. This required a great deal of care on the part of Galdikas, even to the point of sleeping with infant orangutans and waking up in a puddle of orangutan urine and feces (Galdikas 1996). Orangutans are critically endangered due to the pet trade, logging, and palm oil production. Palm oil is especially endangering to orangutans, destroying the last orangutan habitat to make way for palm oil plantations.

Exercises

Chimpanzees and Bonobos

There are two species of chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) and Pan paniscus (bonobo). Chimpanzees live in tropical Africa as well as a savanna environment (Figure 4.25). Like gorillas, chimpanzees are knuckle-walkers. Chimpanzees spend time on the ground and in trees. They prefer fruits and also occasionally eat protein such as mammals, birds, or eggs. Chimpanzees are less sexually dimorphic than gorillas, though males are about 20 percent larger than females. Chimpanzees form multi-male and multi-female troops of up to 60 chimps but typically travel in smaller parties. Of all the primates, they have the highest incidence of tool use, using termite and ant sticks, rocks for nut cracking, leaf sponges, and even a kind of thrusting spear. Female chimpanzees use tools most often.

Males tend to be dominant among chimpanzees. Females move out of their group upon sexual maturity while males remain. This allows males to form coalitions. The coalitions are critically important and based on friendships cemented through grooming—literally scratching each other’s backs. For this reason, chimpanzees are often described as “political.” Dominant males will have preferential access to food and sexual partners. Males also perform dramatic displays—hooting, jumping, dragging objects, and thumping— designed to intimidate other males. Males will also hunt on occasion and eat more meat the females. Chimpanzees and bonobos are the only adult primates besides humans to share food. Chimps share food for many of the same reasons humans do—to support close relatives (mother to offspring), to support friendships (reciprocal altruism), and tolerated theft (protecting the food is more costly than sharing).

Among chimpanzees, females, rather than males, move out of their natal troop (the troop they were born into) into a new troop (dispersal). Males remain in their natal troop and form reciprocal bonds and strong male-male relationships. They also defend their territory and perform silent boundary patrols of their territory. Jane Goodall reported one troop of chimpanzees systematically killing all the males in a neighboring troop that had splintered off from the first group.

Chimps use a wide range of vocalizations from grunts to pant-hoots. They also use gestures. The outstretched hand is used to request an item usually food. Unlike humans, chimps do not point in the wild but can be taught to do so in captive environments.

Female chimpanzees undergo an obvious ovulation cycle called estrus, which is marked by a large red genital swelling. Male chimps are only interested in copulation during estrus. Male chimpanzees also prefer to mate with older females because they are more competent mothers than younger female chimpanzees.

Bonobos have been isolated from chimpanzees for about a million years by the Congo River, and they have diverged somewhat because of their isolation from each other. Neither chimps nor bonobos can swim. A brief story illustrates this point. In 1990, Joe-Joe, a chimpanzee at the Detroit Zoo, fell into the retaining moat and sank to the bottom in front of onlookers. Truck driver Rick Swope realized Joe-Joe was drowning, jumped a short fence, hopped in the water, and found Joe-Joe face down at the bottom of the moat. Swope dragged the chimpanzee out of the water, squeezing the water out of the chimp as he hauled him ashore. Swope was face-to-face with Joe-Joe, and Swope said the chimp looked grateful. The next day, Swope, who simply left the zoo with his family, was in the newspapers (Chicago Tribune 1990). Chimpanzees’ complete inability to swim makes the recent discovery of Fongoli chimps playing in water all the more remarkable.

While bonobos look very similar to chimpanzees, their hair is parted in the middle, and they are smaller and have dark faces at birth, they are socially very different (Figure 4.26). Among bonobos, females tend to be more dominant and display by dragging objects. Male bonobos, who stay in their natal group, get their status from their high-ranking mothers. Overall, bonobos are less aggressive than chimpanzees and resolve social tension through sexual behavior. Bonobos engage in non-reproductive sexual behavior, sex not intended for reproduction, by rubbing genitals, rump rubbing, “penis-fencing,” and other same-sex and opposite-sex sexual behavior. This non-reproductive behavior is used to alleviate social stress, especially among females. Bonobos are not the only non-human primates to engage in same-sex interactions. Numerous species engage in sex not directly related to procreation as described in Joan Roughgarden’s book Evolution’s Rainbow. For instance, Japanese macaques in Mindoo in central Japan exhibit female-female sexual interactions and even monkey-deer sexual interactions (Gunst et al. 2018).

Exercises

Chimp Retirement

Since humans and chimps are so similar genetically, biomedical research on chimps began in the United States in the 1960s. Chimps were taken from Africa and sent to newly created primate research centers. The U.S. government stopped importing chimpanzees from Africa in 1973 and began a breeding program. Captive chimps reached their peak in 1996 when 1500 chimpanzees lived at primate centers, including one in Alamogordo, New Mexico. In 2013, a report came out from the Institute of Medicine saying that invasive research on chimpanzees was unnecessary, and as a result, the National Institutes of Health decided to stop supporting invasive research on chimps (Kaiser 2013). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) declared U.S. captive chimps endangered, ending all biomedical research (Grimm 2015). All but 50 of the 350 federally owned chimps were slated for retirement (Grimm 2017). Chimp Haven near Shreveport, Louisiana, is a retirement sanctuary for biomedical research chimps. But retirement has been slower than expected due to funding, health issues, transportation, and difficulties with reintegration. Today, the Alamogordo Primate Research Facility still houses 126 chimps.

Primate Conservation: The Human Toll

The relationship between humans and other primates has been the source of increasing study and interest and now has its own name, ethnoprimatology. According to a 2017 study, 60 percent of primates are threatened with extinction and 75 percent of species are declining (Estrada et al. 2017). Perhaps not too surprisingly, people are the problem. Logging, deforestation, mining, poaching, and social unrest are common causes of primate decimation. Protecting primates is not a simple task. As many as 150 rangers in Virunga National Park, Africa’s oldest national park and mountain gorilla refuge, have lost their lives defending the park and the gorillas from poachers and rebel militias (Howard 2016). Today, thanks to the continued dedication of the rangers, the numbers of mountain gorillas in the park are low but increasing. Sadly, Virunga National Park closed in 2018 in response to the murder of a ranger and the kidnapping of two tourists and their driver (Sims 2018).

Mountain gorilla conservation has not been straightforward concerning local populations. The Batwa forest dwellers of Uganda were displaced from the Bwindi Impenetrable forest where they lived as hunter-gatherers for almost certainly thousands of years. The Batwa were removed at gunpoint to make way for a mountain gorilla national parks (Bwindi Impenetrable and Mgahinga Gorilla National Parks) and gorilla ecotourism. The Batwa were not compensated for their land because, as traditional hunter-gatherers, there was no land ownership. Today, the Batwa live on the periphery of their ancestral lands, unable to hunt and gather in the forest. Child mortality is high, with 40 percent dying before the age of five. Batwa work as farmhands for food or low wages, or sometimes they dress in fake animal skins and dance for tourists. In a recent article for the BBC, it was reported, “According to Mr. Muhangi from the wildlife authority, from each $600 fee paid by a tourist for a gorilla trek, $8 is allocated to local communities but nothing goes directly to the Batwa” (BBC News 2016). They also face extreme discrimination. One woman was set on fire for foraging in a farmer’s garden (she survived). Recently, a Batwa man was arrested for killing a duiker, a small antelope, and is being held by police (Survival International 2017). As a result of their eviction, the Batwa live in squalor, and malaria, AIDS, malnutrition, and alcoholism have taken hold. The Batwa, in effect, have become conservation refugees, not so different from the San who were evicted from the Kalahari Game Preserve.

Attribution

This chapter is a combination of the following sources:

Susan Ruth, “Chapter 7: Primates” in Being Human which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Stephanie Etting, “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates,” In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, (second edition), edited by Beth Shook, Lara Braff, Katie Nelson, and Kelsie Aguilera, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. (The second edition of the chapter is a revision of “Chapter 5: Meet the Living Primates” by Stephanie Etting. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.)

A grouping based on overall similarity in lifestyle, appearance, and behavior.

A grouping based on ancestral relationships; a branch of the evolutionary tree.

A trait that has been inherited from a distant ancestor.

A trait that has been recently modified, most helpful when assigning taxonomic classification.

A trait that is useful for a wide range of tasks.

Having thumbs and toes that go in a different direction from the rest of the fingers, allows for grasping with hands and feet.

A trait that has been modified for a specific purpose.

The broad pattern of a species’ life cycle, including development, reproduction, and longevity.

A descriptor for an organism that spends most of its time in trees.

Having five digits or fingers and toes.

When an organism, which is limited in the time and energy it can put into aspects of its biology and behavior, is shaped by natural selection to invest in one adaptation at the expense of another.

A bony ring that surrounds the eye socket, open at the back.

Wet noses; resulting from naked skin of the nose which connects to the upper lip and smell-sensitive structures along the roof of the mouth.

The behavior of rubbing scent glands or urine onto objects as a way of communicating with others.

Reflecting layer at the back of the eye that magnifies light.

A specialized form of arboreal locomotion seen in many primates like tarsiers, and galagos.

Being able to distinguish yellows and reds in addition to blues and greens.

A depressed area in the retina at the back of the eye containing a concentration of cells that allow one to focus on objects very close to one’s face.

When males and females of a species have similar morphological traits.

Modified seat bones of the pelvis that are flattened and over which calluses form; function as seat pads for sitting and resting atop branches.

efers to the contrasting fur color of baby leaf monkeys compared to adults.

When a species exhibits sex differences in morphology, behavior, hormones, and/or coloration.

A form of quadrupedal movement used by Gorilla and Pan when on the ground, wherein the front limbs are supported on the knuckles of the hands.

A subarea of anthropology that studies the complexities of human-primate relationships in the modern environment.